Difference between revisions of "Asimina obovata"

HaleighJoM (talk | contribs) (→Ecology) |

HaleighJoM (talk | contribs) (→Ecology) |

||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

Associated species include ''Befaria racemosa, [[Sabal etonia]], [[Carya floridana]], [[Cnidoscolus stimulosus]], Helianthemum nashii, Linaria canadensis, [[Mimosa quadrivalvis]], Pinus clausa, [[Palafoxia feayi]], [[Pinus elliottii]]'' var ''densa'', ''[[Polygonella polygama]], [[Polygonella robusta]], [[Quercus chapmanii]], [[Quercus geminata]], [[Quercus inopina]], [[Quercus myrtifolia]], Ceratiola ericoides, [[Ilex opaca]]'' var. ''arenicola'', [[Garberia heterophylla]], [[Quercus laevis]], [[Quercus geminata]], [[Serenoa repens]], [[Opuntia humifusa]], [[Pinus palustris]], [[Tephrosia chrysophylla]], [[Lyonia ferruginea]], [[Licania michauxii]], [[Asimina reticulata]], Stylisma abdita, [[Stylisma patens]], Krameria lanceolata, [[Asclepias verticillata]], [[Polygala polygama]], [[Smilax auriculata]], [[Stipulicida setacea]], [[Tillandsia usneoides]], & [[Vitis rotundifolia]]'', and ''Persea humilus.''<ref>Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: May 2021. Collectors: J. Richard Abbott, Charlotte Germain-Aubrey, Doug Goldman, and Scott Zona. States and counties: Florida: Citrus County and Highlands County</ref> | Associated species include ''Befaria racemosa, [[Sabal etonia]], [[Carya floridana]], [[Cnidoscolus stimulosus]], Helianthemum nashii, Linaria canadensis, [[Mimosa quadrivalvis]], Pinus clausa, [[Palafoxia feayi]], [[Pinus elliottii]]'' var ''densa'', ''[[Polygonella polygama]], [[Polygonella robusta]], [[Quercus chapmanii]], [[Quercus geminata]], [[Quercus inopina]], [[Quercus myrtifolia]], Ceratiola ericoides, [[Ilex opaca]]'' var. ''arenicola'', [[Garberia heterophylla]], [[Quercus laevis]], [[Quercus geminata]], [[Serenoa repens]], [[Opuntia humifusa]], [[Pinus palustris]], [[Tephrosia chrysophylla]], [[Lyonia ferruginea]], [[Licania michauxii]], [[Asimina reticulata]], Stylisma abdita, [[Stylisma patens]], Krameria lanceolata, [[Asclepias verticillata]], [[Polygala polygama]], [[Smilax auriculata]], [[Stipulicida setacea]], [[Tillandsia usneoides]], & [[Vitis rotundifolia]]'', and ''Persea humilus.''<ref>Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: May 2021. Collectors: J. Richard Abbott, Charlotte Germain-Aubrey, Doug Goldman, and Scott Zona. States and counties: Florida: Citrus County and Highlands County</ref> | ||

| − | ===Phenology===<!--Timing off flowering, fruiting | + | ===Phenology===<!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> |

Flowers March to June<ref name="Kral"></ref> with white flowers and green fruit.<ref name="FNPS"/> | Flowers March to June<ref name="Kral"></ref> with white flowers and green fruit.<ref name="FNPS"/> | ||

''Asimina obovata'' is the only species in the genus ''Asimina'' to have flower buds that terminate the new shoot growth.<ref name="Kral"></ref> This species can be identified by a bright red-hairy peduncle and a reddish pubescence on the shoots and lower leaf surface.<ref name="Kral"></ref> The stamens are pale green to beige at anthesis.<ref name="Archbold"/> | ''Asimina obovata'' is the only species in the genus ''Asimina'' to have flower buds that terminate the new shoot growth.<ref name="Kral"></ref> This species can be identified by a bright red-hairy peduncle and a reddish pubescence on the shoots and lower leaf surface.<ref name="Kral"></ref> The stamens are pale green to beige at anthesis.<ref name="Archbold"/> | ||

| + | |||

<!--===Seed dispersal===--> | <!--===Seed dispersal===--> | ||

Revision as of 19:22, 15 June 2022

| Asimina obovata | |

|---|---|

| |

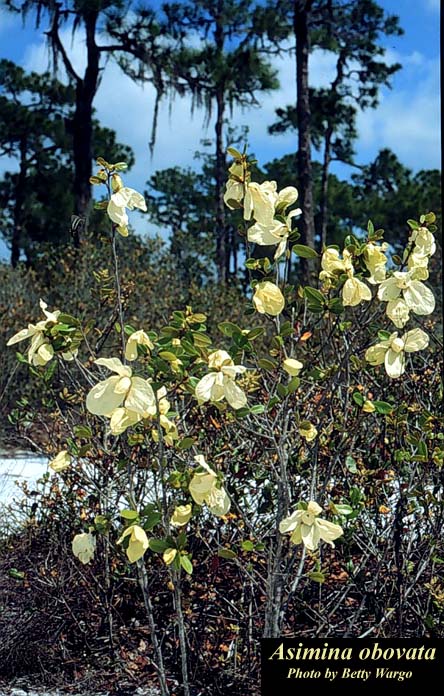

| Photo by Betty Wargo, Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Magnoliales |

| Family: | Annonaceae |

| Genus: | Asimina |

| Species: | A. obovata |

| Binomial name | |

| Asimina obovata (Willd.) Nash | |

| |

| Natural range of Asimina obovata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Bigflower pawpaw

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonym: Pityothamnus obovatus (Willdenow) Small.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

A description of Asimina obovata is provided in The Flora of North America.

Asimina obovata is a long-lived perennial.[2] Such as other species in the Genus Asimina, it has a deep taproot and resprouts from a lignotuber after fire or disturbance[3] (Kral 1993). Leaves are alternate and simple with pinnate venation.[4] It can be a shrub or a small tree growing three meters or more.[5]

Asimina obovata does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its taproot.[6] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 72 mg/g (ranking 61 out of 100 species studied).[6]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

Asimina obovata is endemic to the well drained sand of sand ridges, coastal dunes, hammocks and pine-turkey oak sand ridges that occur in southeastern to north central Florida.[3] A. obovata has been found in regularly burned sandhill habitats, pine savannas, and slash pine flatwood. Additionally, it is found in disturbed areas like fire suppressed, sandy, open roadsides.[7]

Associated species include Befaria racemosa, Sabal etonia, Carya floridana, Cnidoscolus stimulosus, Helianthemum nashii, Linaria canadensis, Mimosa quadrivalvis, Pinus clausa, Palafoxia feayi, Pinus elliottii var densa, Polygonella polygama, Polygonella robusta, Quercus chapmanii, Quercus geminata, Quercus inopina, Quercus myrtifolia, Ceratiola ericoides, Ilex opaca var. arenicola, Garberia heterophylla, Quercus laevis, Quercus geminata, Serenoa repens, Opuntia humifusa, Pinus palustris, Tephrosia chrysophylla, Lyonia ferruginea, Licania michauxii, Asimina reticulata, Stylisma abdita, Stylisma patens, Krameria lanceolata, Asclepias verticillata, Polygala polygama, Smilax auriculata, Stipulicida setacea, Tillandsia usneoides, & Vitis rotundifolia, and Persea humilus.[8]

Phenology

Flowers March to June[3] with white flowers and green fruit.[2]

Asimina obovata is the only species in the genus Asimina to have flower buds that terminate the new shoot growth.[3] This species can be identified by a bright red-hairy peduncle and a reddish pubescence on the shoots and lower leaf surface.[3] The stamens are pale green to beige at anthesis.[9]

Seed bank and germination

Seedlings have been found in the shade of parent plants due to the importance of shade and seed burial to prevent seed desiccation after ripening.[7]

Fire ecology

In the year following a fire, A. obovata resprouts with more stems than were present pre-fire, however these stems are smaller and less woody with a higher chance of herbivory. The amount of flowers blooming is the greatest in the second flowering season post-fire with flower numbers decreasing as the fire interval becomes longer.[9]

The species responds to a disturbance such as fire or cutting vegetatively, sending up several leafy shoots which are forming flower buds that do not open until the following growing season.[3]

Pollination

Pollination occurs entomophily [10] with beetles such as Typocerus zebra, Trichotinus rufobruneus, T. lunulatus and Euphoria sepulchralis responsible for pollination.[11] Asimina obovata was observed at the Archbold Biological Station with bees such as Apis mellifera (family Apidae) and wasps such as Polistes dorsalis hunteri (family Vespidae).[12]

Herbivory and toxicology

In order to protect itself from herbivory, A. obovata contains a toxin called annonaceous acetogenins which inhibits mitochondrial respiration in predators.[10] Gopher tortoises have been observed to eat the ripe fruit and spit out the seeds.[11]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Global conservation status: G3-Vulnerable.[13] State status: S3-Vulnerable.[13]

Cultural use

The fruit of A. triloba is known to be sweet and custard-like. It was often used in baking, pie filling, or eaten raw. The fruits fall from the tree early and must be harvested from the ground to ripen later.[14] For medicinal purposes, the seeds can be used to induce vomiting or to treat head lice when powdered, and the fruit juice can be a treatment for intestinal worms.[15] Caution should be exercised though, as some people exhibit an allergic reaction of dermatitis to the fruit.[16]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 [Florida Native Plant Society. Accessed: November 24, 2015]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Kral, Robert. 1960. A Revision of Asimina and Deeringothamnus (Annonaceae). Brittonia 12:233-278.

- ↑ [Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: November 23, 2015.]

- ↑ [[1]]Accessed: November 24, 2015.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Crummer, Kathryn. Physiological Leaf Traits of Scrub Pawpaw, Asimina obovata (Willd.)Nash (Annonaceae). University of Florida, 2003.

- ↑ Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: May 2021. Collectors: J. Richard Abbott, Charlotte Germain-Aubrey, Doug Goldman, and Scott Zona. States and counties: Florida: Citrus County and Highlands County

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 [[2]] Archbold Biological Station. Accessed: November 24, 2015

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 [Encyclopedia of Life]Accessed November 24, 2015

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Norman, Elaine M. and David Clayton. Reproductive Biology of Two Florida Pawpaws: Asimina obovata and A. pygmaea (Annonaceae). 1986. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 113: 16-22.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 [[3]] Nature Serve Explorer. Accessed November 24, 2015.]]

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.

- ↑ Burrows, G.E., Tyrl, R.J. 2001. Toxic Plants of North America. Iowa State Press.