Stipulicida setacea

| Stipulicida setacea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Shirley Denton (Copyrighted, use by photographer’s permission only), Nature Photography by Shirley Denton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Caryophyllaceae |

| Genus: | Stipulicida |

| Species: | S. setacea |

| Binomial name | |

| Stipulicida setacea Michx. | |

| |

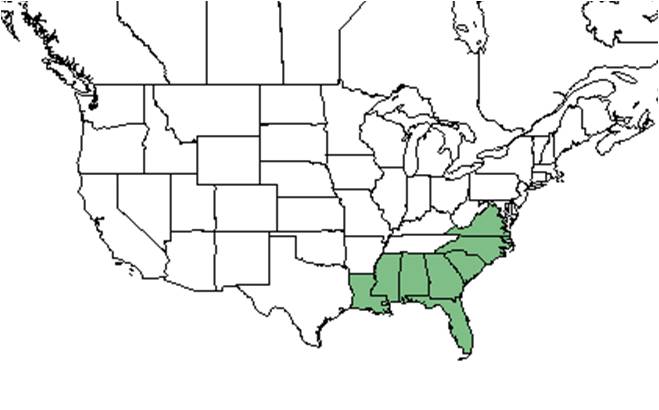

| Natural range of Stipulicida setacea from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Pineland scalypink, Coastal Plain wireplant

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Variations: Stipulicida setacea Michaux var. lacerata.[1]

The genus name Stipulicida derives from the Greek meaning for fibers. The specific epithet setacea comes from the Latin word for bristle- which refers to the tiny leaves that resemble bristles.[2]

Description

A description of Stipulicida setacea is provided in The Flora of North America.

The root system of Stipulicida setacea includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[3] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 44 mg/g (ranking 78 out of 100 species studied).[3]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Stipulicida setacea has stem tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.916 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 44 mg g-1.[4]

Distribution

The Stipulicida genera is endemic to the longleaf pine range from southeastern Virginia to central Florida and west to southeast Texas, and is disjunct to Cuba.[5]

S. setacea is found along the Coastal Plain from Virginia down to Florida and west to Louisiana. It is critically imperiled in Virginia and Louisiana.[6]

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain, S. setacea habitats include shrubless barrens, sandhill clearings in oak woodlands, sand pine-oak scrubs, longleaf pine-saw palmetto flatwoods, surrounding cypress wetlands, oak-hickory hammock forests, open oak-hickory-sand pine scrubs, and slash pine woodlands bordering tidal marshes. It occurs in disturbed areas such as powerline corridors, grassy roadsides, sandy old fields, parking areas, moist banks of drainage canals, and a pineapple field. Soil types include loamy sand, sand, and sandy peat.

S. setacea has shown regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine woodlands that were disturbed by agriculture in South Carolina coastal plain communities, making it a possible indicator species for post-agricultural woodlands.[7]

Associated species include Lupinus diffusus, Arenaria caroliniana, Opuntia, Parnoychia erecta, Polygonella robusta, Helianthemum, Vaccinium, and Crataegus.[8]

Phenology

S. setacea has white flowers, usually in clusters of three; with five petals, three stamen, and three lobed ovaries.[8] The flowers are not notched at the tips, unlike many members of this family.[9] The fruit is a small capsule with a small yellowish seed. Flowers March through June and fruits May through August.[8][10]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[11]

Seed bank and germination

It has been observed that the seed bank after fire in the Florida rosemary scrub was dominated by S. setacea.[12][13] At one site there were more seeds present in the seed bank than adults in the Florida rosemary scrub.[13] It was found viable in the seed bank of a pine flatwoods community in Florida following fire after 8 years of fire exclusion.[14] Stipulicida setacea forms a persistent soil seed bank.[15]

Fire ecology

S. setacea is a seeder species that occasionally resprouts after fire.[16] Post-fire, it has been observe to dominate the seed bank in the Florida rosemary scrub.[12] It has been observed growing in burned pinewoods.[8]

Pollination

Sweat bees (Lasioglossum nymphalis, family Halictidae), leafcutting bees (Anthidiellum notatum rufomaculatum, family Megachilidae) and wasps (Leptochilus krombeini and Microdynerus monolobus, family Vespidae) were observed visiting flowers of Stipulicida setacea at the Archbold Biological Station:[17]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Threats include shoreline and barrier island erosion and fire exclusion. Beneficial management practices include shoreline and island stabilization and prescribed burning or mowing.[9]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ [[1]]Alabama Plants. Accessed: March 17, 2016

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ Sorrie, B. A. and A. S. Weakley 2001. Coastal Plain valcular plant endemics: Phytogeographic patterns. Castanea 66: 50-82.

- ↑ [[2]]NatureServe. Accessed: March 17, 2016

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: November 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Leonard J. Brass, James Buckner, Delzie Demaree, R.B. Channel, George R. Cooley, A.H. Curtiss, Wilbur H. Duncan, Bob Fewster, Angus Gholson, Robert K. Godfrey, H.A. Hespenheide, Edwin Keppner, Brian R. Keener, Robert Kral, S.W. Leonard, Sidney McDaniel, Marc Minno, John B. Nelson, Elmer C. Prichard, A.E. Radford, Paul Redfearn, William Reese, Annie Schmidt, Robert Simons, Cecil R. Slaughter, John K. Small, Wayne K. Webb, R.L. Wilbur, Kenneth A. Wilson, Carroll E. Wood Jr.. States and Counties: Alabama: Autauga, Baldwin, Henry Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Escambia, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Highlands, Hillsborough, Holmes, Indian River, Lee, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Marion, Martin, Osceola, Palm Beach, Polk, St. Lucie, St. Johns, Volusia, Wakulla,Walton, Washington. Georgia: Ben Hill, Laurens, McDuffie, Richmond, Wheeler. Mississippi: Jackson. North Carolina: Bladen, Craven, Moore, Robeson. South Carolina: Lexington, Richland. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 [[3]]Accessed: March 17, 2016

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 19 MAY 2021

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Carrington, M. E. (1997). "Soil Seed Bank Structure and Composition in Florida Sand Pine Scrub." The American Midland Naturalist 137(1): 39-47.

- ↑ Maliakal, S.K., E.S. Menges and J.S. Denslow. 2000. Community composition and regeneration of Lake Wales Ridge wiregrass flatwoods in retlation to time-since-fire. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 127:125-138.

- ↑ Navarra, J. J., N. Kohfeldt, et al. (2011). "Seed bank changes with time since fire in Florida rosemary scrub." Fire Ecology 7(2).

- ↑ Dee, J. R. and E. S. Menges (2014). "Gap ecology in the Florida scrubby flatwoods: effects of time-since-fire, gap area, gap aggregation and microhabitat on gap species diversity." Journal of Vegetation Science 25(5): 1235-1246

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.