Smilax auriculata

| Smilax auriculata | |

|---|---|

| |

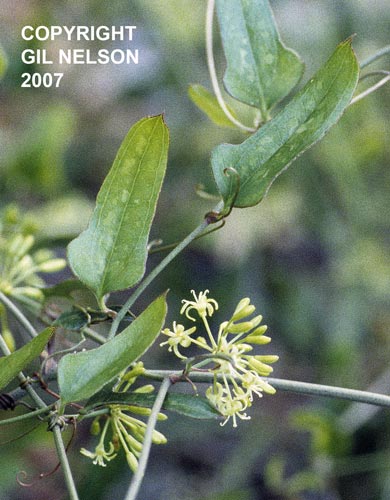

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta – Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida – Monocotyledons |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Smilacaceae |

| Genus: | Smilax |

| Species: | S. auriculata |

| Binomial name | |

| Smilax auriculata Walter | |

| |

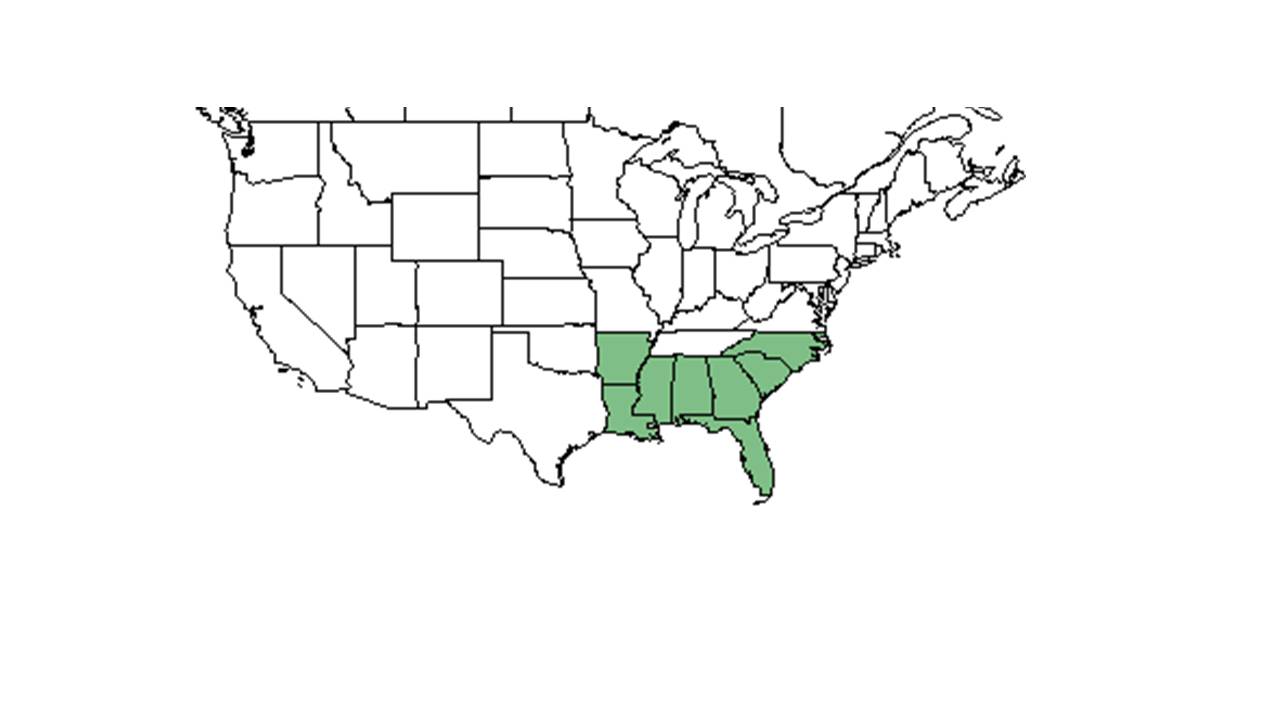

| Natural range of Smilax auriculata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Earleaf greenbrier, Dune greenbrier, Wild-bamboo

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Description

A description of Smilax auriculata is provided in The Flora of North America.

Smilax auriculata does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its rhizomes.[1] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 361.1 mg/g (ranking 10 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 58.7% (ranking 67 out of 100 species studied).[1]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Smilax auriculata has stem tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 11.665 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 361.1 mg g-1.[2]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain, specifically in Florida and Georgia, S. auriculata can be found bordering mesic woodlands, longleaf pine turkey oak sand ridges,[3] palmetto flatwoods,[3][4] oak-saw palmetto scrubs,[5] sandhill communities,[3][6] xeric longleaf pine woodlands (Peet and Allard 1993), and unburned scrubby flatwoods.[7] It can also be found along railroads, powerline corridors, and disturbed longleaf pine restoration sites.[3] Soil types include loamy sand[8][5] and sandy, siliceous, hyperthermic Ultic haplaquod of the Pomona series.[9]

S. auriculata does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[10]

In habitats that include Pinus palustris, Quercus laevis, Q. incana, Sporobolus junceus and Licania michauxii, S. auriculata accounts for most of the groundcover density.[11]

Smilax auriculata is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula and Panhandle Xeric Sandhills, the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands and Subxeric Sandhills, the Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands, and Xeric Flatwoods community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[12]

Phenology

S. auriculata has been observed flowering in April and May and fruiting June through July.[3][13]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[14]

Seed bank and germination

It can reproduce by resprouting, clonal spreading, and seeding.[7]

Fire ecology

Populations of Smilax auriculata have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[15][16] It increases in abundance after fire,[7] and its rapid recovery post-fire can be attributed to large specialized storage organs.[4] However, it was figured out that S. auriculata decreased to almost nonexistent following a May fire, suggesting that season of burning is important for this species.[17]

Pollination

Smilax auriculata has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host pollinator species such as Apis mellifera (family Apidae), Augochlora pura (family Halictidae), and bees from the Megachilidae family such as Coelioxys dolichos, Megachile mendica, and M. xylocopoides.[18] Deyrup (2002) observed Augochlora pura, Coelioxys dolichos, Megachile mendica, M. xylocopoides, Apis mellifera, Xylocopa micans and X. virginica krombeini, on S. auriculata.[19]

Herbivory and toxicology

S. auriculata was found in 5.5% of the Gopherus polyphemus scat[20] therefore, the gopher tortoise serves as an agent of seed dispersal.

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

There are many species of Smilax and it is thought they can all be used in similar ways. Historically, the roots were harvested and prepared in a red flour or a thick jelly that could be used in candies and sweet drinks. Our first known written account of using the plant roots to make this jelly is from the journal of Captain John Smith in 1626. Other travelers throughout US history have made note of the uses of Smilax plants. We know the flour was used in breads and soups, and that a drink very similar to Sarsaparilla could be prepared.[21]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: July 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Robert K. Godfrey, Robert A. Norris, R. Komarek, Cindi Stewart, Cecil R Slaughter, Marc Minno, Bob Fewster, Lisa Keppner. States and Counties: Florida: Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Jackson, Leon, Wakulla, Washington. Georgia: Camden. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Olano, J. M., E. S. Menges, et al. (2006). "Carbohydrate storage in five resprouting Florida scrub plants across a fire chronosequence." New Phytologist 170: 99-105.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Foster, Tammy E., Paul A. Schmalzer. (2003). "The effect of season of fire on the recovery of Florida scrub". Dynamac Corporation, Kennedy Space Center, Florida. 2B.7.

- ↑ Reinhart, K. O. and E. S. Menges (2004). "Effects of re-introducing fire to a central Florida sandhill community." Applied Vegetation Science 7: 141-150.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Menges, E. and N. Kohfeldt (1995). "Life History Strategies of Florida Scrub Plants in Relation to Fire." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 122(4): 282-297

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedFSU herbarium - ↑ Moore, W. H., B. F. Swindel, et al. (1982). "Vegetative response to prescribed fire in a north Florida flatwoods forest." Journal of Range Management 35: 386-389.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Provencher, L. M., B. J. Herring, et al. (2001). "Effects of hardwood reduction techniques on longleaf pine sandhill vegetation in northwest Florida." Restoration Ecology 9: 13-27.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 13 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Greenberg, C. H. (2003). "Vegetation recovery and stand structure following a prescribed stand-replacement burn in sand pine scrub." Natural Areas Journal 23: 141-151.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Deyrup, Mark., Jayanthi Edirisinghe, Beth Norden. (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea). Insecta Mundi. Vol. 16. No.1-3. Pages 87-102.

- ↑ Carlson, J. E., E. S. Menges, et al. (2003). "Seed dispersal by Gopherus polyphemus at Archbold Biological Station, Florida." Florida Scientist 66: 147-154.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.