Carya tomentosa

Common name: Mockernut Hickory; White Hickory

| Carya tomentosa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Juglandales |

| Family: | Juglandaceae |

| Genus: | Carya |

| Species: | C. tomentosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Carya tomentosa Lam. | |

| |

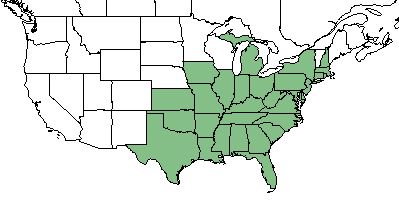

| Natural range of Carya tomentosa from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Hicoria alba (L.) Britton.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

C. tomentosa, also known as mockernut hickory, is a native perennial in the Juglandaceae family[2] that normally reaches heights of 50 - 60 feet, but can grow to 100 feet in good soil. The bark has a net-like pattern which is rough and thin with narrow ridges and shallow furrows. The leaves are pinnately compound, deciduous, and turn golden-yellow in the fall; the undersurface of leaves is densely covered with soft hairs. The nuts are small and barely edible, and are inside a thick, large shell.[3]

Distribution

The species can be found throughout most of Eastern United States, ranging from Texas and Kansas to New Hampshire and Michigan [2].

Ecology

Habitat

C. tomentosa can be found in forests and woodlands including communities ranging from mesic hammocks to pine sandhills.[4][5] More specifically, the habitats range from mixed hardwood forests, disturbed meadows, in sandy soil of mesic woods, rich deciduous woods, hardwood hammocks, wooded ravines, and loamy sand woodlands.[6] It has been found to decrease in frequency in areas that are managed for red-cockaded woodpeckers.[7] C. tomentosa is a canopy sub-dominant species in the longleaf pine communities, and is a characteristic species of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands.[8][9] C. tomentosa responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina communities, marking it as an indicator for remnant woodlands.[10]

Associated species: Pinus palustris, Quercus hemisphaerica, Quercus incana, Quercus falcata, Quercus virginiana, and Quercus laevis [4].

Phenology

C. tomentosa is known to flower in April.[3] Fruit has been seen to be present from March to May and July as well as the month of October. [6]

Seed dispersal

C. tomentosa is dispersed through various mammals found in the pine sandhills community.[11]

Seed bank and germination

For propagation purposes, C. tomentosa is easily grown from fresh seeds that are sown either immediately from collection or stratified first and sown in the spring. The nuts should be collected between September and November when the tree is fruiting, and embryo dormancy is possible to overcome by moist stratification between 33 and 40 degrees for a duration of 30 to 150 days. This is since older seeds need less stratification.[3]

Fire ecology

C. tomentosa has been shown to significantly decrease in frequency when prescribed fire regiments are introduced.[12] Species in the Carya genus have been found to colonize sites when fire becomes absent in areas that were once burned and dominated by longleaf pine.[13] In a study of fire exclusion, Clewell found that C. tomentosa thrived in the system to create a shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodland over 44 years from an original upland pine savanna community.[14] Populations of Carya tomentosa have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[15]

Herbivory and toxicology

The consort underwing (Catocala consors) was been found to feed on species in the Carya genus.[16] It serves as a larval host for some moths, including the Luna moth (Actias luna), the funeral dagger (Acronicta funeralis), and the giant regal (Citheronia regalis). The tree as a whole attracts birds and butterflies.

Diseases and parasites

Trees that are stressed are more susceptible to hickory bark beetle.[3]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

For humans, the wood is used for flooring, furniture, baseball bats, tool handles, veneer, and skis. Hickory wood is also utilized for both firewood and charcoal, and is preferred for smoking ham.[3] The bark of hickories has been used medicinally for indigestion and intermittent fever. As well, the bark can be used to make a natural dye, varying in color from yellow to olive green depending on how it is prepared.[17]The nuts are used to create a Cherokee hickory nut soup that is remains a holiday tradition in Cherokee communities.[18]

In addition to the nuts being edible raw, Native Americans would use the tree for all sorts of culinary resources. Members of the Carya genus have a sap that makes an excellent syrup, the nuts can be boiled in order to make a butter from the oil that comes off and then the meat can be eaten or preserved. The oil butter or gravy could be used as a spread on food, or it could be utilized as a hair oil.[19]

The word "hickory" comes from the native peoples who would make this oil; they were known as the powcohicora people, which white settlers shortened to hickory.[20]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 USDA Plants Database URL: https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=CATO6

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 2, 2019

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.

- ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Cecil R. Slaughter, Travis MacClendon, Karen MacClendon, Cindi Stewart, Loran C. Anderson, R. K. Godfrey, Gwynn W. Ramsey, R. S. Mitchell, Donald E. Stone, R. Kral, Victoria I. Sullivan, Patricia Elliott, H. Kurz, and Palmer Kinser. States and counties: Florida: Nassau, Washington, Leon, Wakulla, Jackson, Liberty, Suwannee, Gadsden, Calhoun, and Alachua.

- ↑ Bowman, J. L., et al. (1999). Effects of red-cockaded woodpecker management on vegetative composition and structure and subsequent impacts on game species. Proceedings of the Fifty-third Annual Conference, Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. A. G. Wong, P. Doerr, D. Woodward, P. Mazik and R. Lequire. Greensboro, NC, Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies: 220-234.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2013). "Prior prevalence of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands in the Tallahassee red hills." Castanea 78(4): 266-276.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Myster, R. W. and S. T. A. Pickett (1993). "Effects of litter, distance, density and vegetation patch type on post dispersal tree seed predation in old fields." Oikos 66: 381-388.

- ↑ Hartman, G. W. and B. Heumann (2003). Prescribed fire effects in the Ozarks of Missouri: the Chilton Creek Project 1996-2001. Second International Wildland Fire Ecology and Fire Management Congress and Fifth Symposium on Fire and Forest Meteorology, Orlando, FL, American Meteorological Society.

- ↑ Archer, J. K., et al. (2007). "Changes in understory vegetation and soil characteristics following silvicultural activities in a southeastern mixed pine forest." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 134: 489-504.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. and L. Deyrup (2012). "The diversity of insects visiting flowers of saw palmetto (Arecaceae)." Florida Entomologist 95(3): 711-730.

- ↑ Porcher, F. P. (1869). Resources of the southern fields and forests, medical, economical, and agricultural. Richmond, VA, Order of the Surgeon-General.

- ↑ Putz, F.E. 2013. Mockernut Hickory: A Hard Nut to Crack. Palmetto 30(4):8-9, 15.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.