Quercus virginiana

Common name: live oak [1]

| Quercus virginiana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Gwaltney hosted at Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Fagaceae |

| Genus: | Quercus |

| Species: | Q. virginiana |

| Binomial name | |

| Quercus virginiana Mill. | |

| |

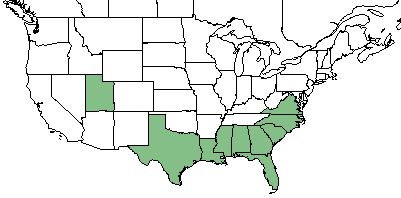

| Natural range of Quercus virginiana from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Q. sempervirens Walter

Varieties: none

Description

Q. virginiana is a perennial tree of the Fagaceae family native to North America.[2]

Distribution

Q. virginiana is found along the southeastern coast of the United States from Texas to Virginia.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

Q. virginiana is locally common to abundant in maritime forests and maritime scrub on barrier islands, more rarely inland (though regularly on the mainland from se. NC south, and extending substantially inland from s. SC south), sometimes in dry, fire-maintained habitats.[1] Specimens have been collected from habitats that include upland woodland, sand ridge, shellmound, sandy loam, open woods, old field, flatwoods, hardwood hammock, pasture, upland field, live oak hammock, mixed woodland, coastal hammock, and mucky sands.[3]

Q. virginiana increased its cover in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods forests.[4] It has also increased its occurrence in response to agriculture in southwest Georgia pinelands.[5] In these reestablished habitats that were disturbed by these activities, this species has shown regrowth.

Phenology

Q. virginiana has been observed to flower in March, April, October, and November.[6]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[7]

Fire ecology

Q. virginiana is not fire resistant and has low fire tolerance[2]; despite this, populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[8][9][10]

Herbivory and toxicology

Quercus virginiana has been observed to host leafhopper species such as Empoasca fabae (family Cicadellidae), bees from the Membracidae family such as Archasia belfragei, Cyrtolobus tuberosus, Ophiderma definita, Smilia camelus and Telamona salvini, and plant bugs from the Miridae family such as Americodema nigrolineatum, Atractotomus miniatus, Hamatophylus guttulosus, Plagiognathus lineatus and Pseudoxenetus regalis, as well as Zelus luridus (family Reduviidae).[11] Hummingbirds are attracted to Q. virginiana. They use the pollen to acquire energy in the spring before migrating. They will also eat insects on the tree and from spider webbs on the tree.[12]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Native Americans used the bark to create treatments for sore eyes and dysentery.[13]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=QUVI

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: R.K. Godfrey, W.D. Reese, M. R. Darst, Sidney McDaniel, Walter S Judd, Angus Gholson, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, R.W. Long, Richard P. Wunderlin, J. Poppleton, S.D. Todd, A.G. Shuey, Gwynn W. Ramsey, H. Kurz, Robert Kral, R.M. Schuster, O. M. Schuster, O. Lakela, R. F. Doren, Elbert L. Little, Walter S. Judd, Paul Kalaz, Elmer C. Prichard, L.B. Trott, B. K. Holst, W. Diaz, Raul Rivero, M. Serrano, K. Wendelberger, Mary E. Nolan, William Stimson, Patricia Elliot, James D. Ray, Jackie Patman, Celeste Baylor, Leon Neel, R. Lomarek, Garret Crow. States and counties: Florida (Pasco, Manatee, Dixie, Leon, Levy, Wakulla, Gadsden, Jeferson, Citrus, Washington, Hillsborough, Jackson, Volusia, Suwannee, Brevard, Madison, Hernando, Marion, Martin, Dade, Bay, Liberty, Hernando, Sarasota, Palm Beach, Okaloosa, Escambia, Pinellas) Georgia (Thomas)

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings 23: 109-120.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 29 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Observation by Roger Hammer in a comment on Steve Gallagher's post in Little Porter Lake, Chipley Florida, Washington County, Fl., March 18, 2018 2016, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.