Carphephorus corymbosus

| Carphephorus corymbosus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Karan A. Rawlins, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Carphephorus |

| Species: | C. corymbosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Carphephorus corymbosus (Nutt.) Torr. & A. Gray | |

| |

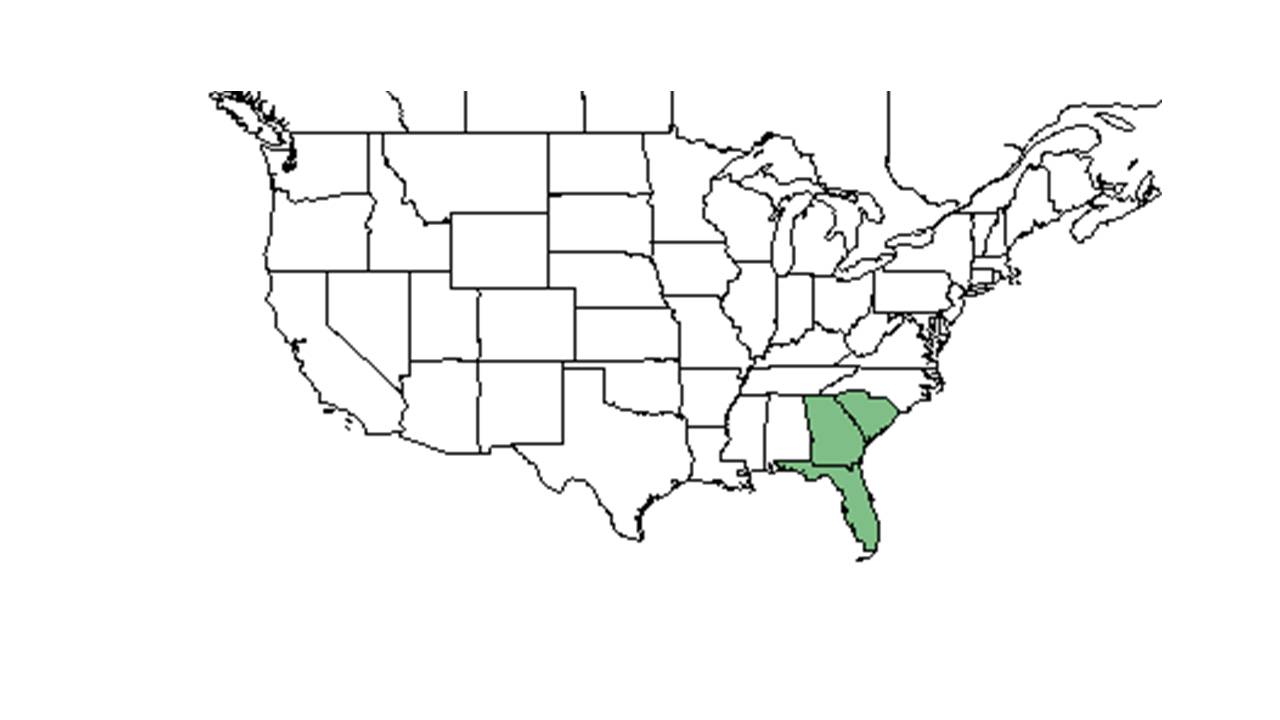

| Natural range of Carphephorus corymbosus from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Coastal Plain Chaffhead; Flatwood Chaffhead

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

A description of Carphephorus corymbosus is provided in The Flora of North America.

Carphephorus corymbosus is a perennial herb consisting of an stemless rosette of spatulate to oblanceolate leaves from thickened, fibrous roots, and a long, green, cylindrical stem which branches into an inflorescence with purple to lavender flowers. Those stems have alternate leaves which distally become progressively smaller.[2]

The root system of Carphephorus corymbosus includes root tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[3]. Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 170.7 mg/g (ranking 29 out of 100 species studied).[3]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Carphephorus corymbosus has root tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 1.46 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 170.7 mg g-1.[4]

Distribution

It can be found in upland sandy habitats of Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina.[5] It occurs in open, sandy areas in sand pine scrub, sandhills, and open pinewood barrens from southeastern Georgia, throughout most of peninsular Florida.[2] In Florida, it is considered endemic to dry prairies and pine flatwoods or savannas in south to south-central Florida.[6]

The Carphephorus genera is endemic to the longleaf pine range from southeastern Virginia to central Florida and west to southeast Texas.[7]

Ecology

Habitat

This species has been found in upland sandhills, dry to relatively wet pinelands, flatwoods, pine-palmettos environments, prairies, and longleaf-scrub oak-wiregrass savannas. [8][9] It can also be found in human disturbed areas such as roadsides, clearings, around powerlines, bulldozed areas, and cut pine forests. This species thrives in open light conditions in dry, loamy sand, drying sand, as well as moist sandy peat of pine-saw palmetto flats.[10] It does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[11]

Carphephorus corymbosusis an indicator species for the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[12]

Associated species include Bigelowia nudata, Liatris laevigata, Coleorachis rugosa, saw palmetto, turkey oak, Quercus virginiana, longleaf pine, slash pine, sand pine, Quercus laevis, Quercus geminata, Quercus incana, and Vaccinium elliottii.[10]

Phenology

In Suwannee River State Park, Florida, terete stems first appear in late May and reach full length by early June. Around mid-June buds develop on the ends of the corymbs; flowers appear in mid-August. Leaf fall occurs in December and the stems and corymbs dry out but remain standing well into the next year, and often may be seen alongside new basal rosettes with stems. On several occasions, a root mass was dug up; it bore a new basal rosette with a stem and an old dried stem from the previous year.[13] C. corymbosus has been observed flowering from June to November, with peak inflorescence in October.[5][14]

Seed bank and germination

Plants in this genus (not identified to species) were found viable in the seed bank of a flatwoods habitat in Florida after more than 30 years of fire exclusion.[15]

Fire ecology

It is fire-tolerant.[9] Heuberger observed that the duration of flowering for C. corymbosus was longer in burned patches.[16] Fires directly and indirectly effect insect abundance –grasshopper densities on the flowering plants (including Carphephrous corymbosus) were significantly affected by burn frequency with higher numbers in one, two and five year plots.[17]

Pollination

Carphephorus corymbosus is visited by sweat bees such as Halictus poeyi (family Halictidae), which were observed visiting flowers of C. corymbosus at the Archbold Biological Station:[18] It is also visited by Papilio glaucus (eastern tiger swallowtail butterfly).[19]

Herbivory and toxicology

Kerstyn found that grasshopper densities on Carphephorus corymbosus were highest on one year, two year, and five year plots. Densities were lowest on the control (unburned) plots and seven year plots. It is possible that burning, which serves to replenish nutrients, results in better plant quality, which would explain why grasshopper densities are greater on more frequently burned plots.[17] Bees, Halictus ligatus Say and Bumelia tenax L. were found on C. corymbosus.[20] C. corymbosus attracts many species of butterflies when in flower. Green lynx spiders are pollinator predators and are often found on the flower heads waiting for a hapless insect to visit.[5]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Corey, D. T. (1992). Comments on the phenology of Carphephorus corymbosus (Compositae). Rhodora 94(879): 323-325.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz-Torbio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannahs in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Hammer, Roger L. Everglades Wildflowers: A Field Guide to Wildflowers of the Historic Everglades: Including Big Cypress, Corkscrew and Fakahatchee Swamps. Guilford: Falcon, 2002. 17. Print.

- ↑ Orzell, S. L. and E. L. Bridges (2006). "Floristic composition of the south-central Florida dry prairie landscape." Florida Ecosystem 1(3): 123-133.

- ↑ Sorrie, B. A. and A. S. Weakley 2001. Coastal Plain valcular plant endemics: Phytogeographic patterns. Castanea 66: 50-82.

- ↑ http://www.dep.state.fl.us/water/wetlands/delineation/featuredplants/carpheph.htm, more citations needed

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Kalmbacher, R., N. Cellinese, et al. (2005). Seeds obtained by vacuuming the soil surface after fire compared with soil seedbank in a flatwoods plant community. Native Plants Journal 6: 233-241.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: July 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, L. Baltzell , Tara Baridi, Robert Blaisdell, Boothes, Richard Carter, A.F. Clewell, George R. Cooley, D. B. Creager, D. B. Creager, F. C. Creager, R. J. Eaton, Nancy Edmonson, Rex Ellis, G. Fleming, P. Genelle, Robert K. Godfrey, S. C. Hood, Richard D. Houk, R. Kral, Kurz, O. Lakela , Bob Lazor, R. W. Long, S.W. Leonard, T. MacClendon, John Morrill, R. E. Perdue, J. E. Poppleton, A. G. Shuey, Cecil R. Slaughter, S. D. Todd, Wagner, R. P. Wunderlin States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Bradford, Brevard, Citrus, Clay, Collier, Dixie, Duval, Hernando, Highlands, Jackson, Lafayette, Levy, Madison, Manatee, Nassau, Osceola, Pinellas, Polk, Putnam , Sarasota, St. Johns, Suwannee, Taylor, Union Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Comments on the Phenology of Carphephorus corymbosus (Compositae) by David T. Corey. Journal: Rhodora, Vol. 94, No 879, pp. 323-325, 1992.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 7 DEC 2016

- ↑ Maliakal, S.K., E.S. Menges and J.S. Denslow. 2000. Community composition and regeneration of Lake Wales Ridge wiregrass flatwoods in retlation to time-since-fire. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 127:125-138.

- ↑ Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Kerstyn, A. and P. Stiling (1999). "The effects of burn frequency on the density of some grasshoppers and leaf miners in a Florida sandhill community." Florida Entomologist 82: 499-505.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Leary, Patrick R. Photograph in Northeast Florida State Forest, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group October 3, 2016.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).