Asimina angustifolia

| Asimina angustifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| photo by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Magnoliales |

| Family: | Annonaceae |

| Genus: | Asimina |

| Species: | A. angustifolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Asimina angustifolia Raf. | |

| |

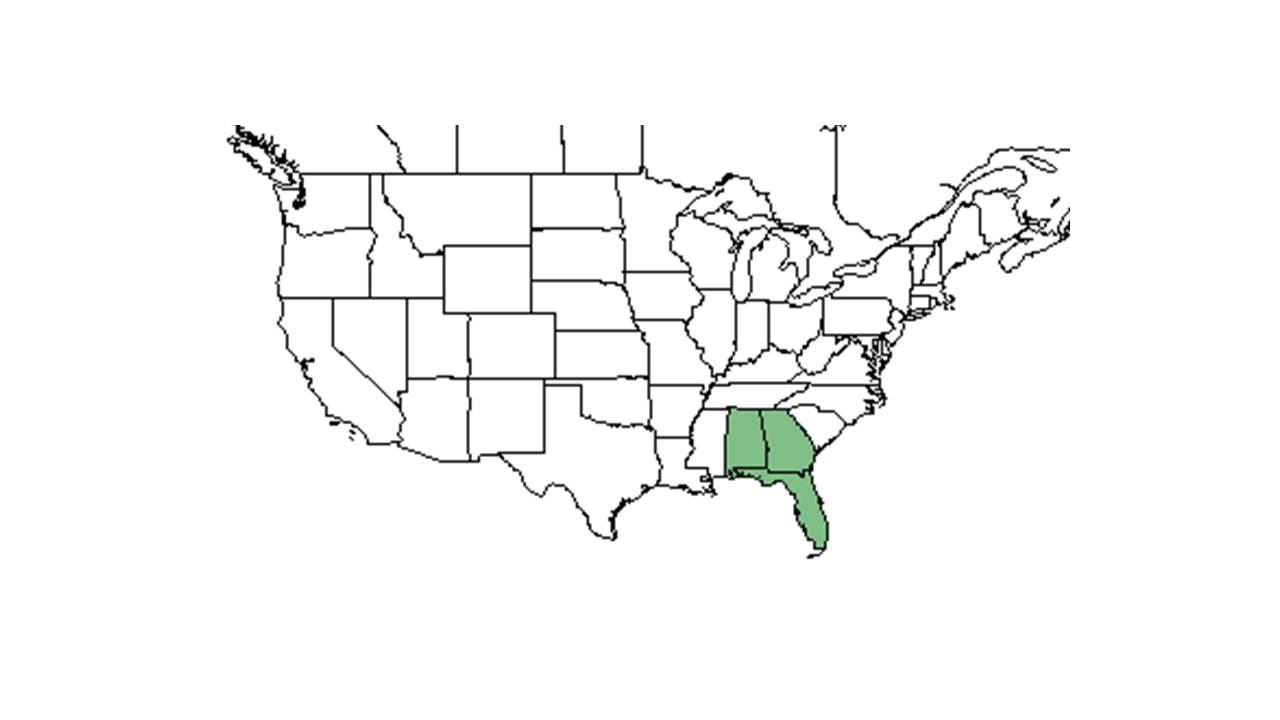

| Natural range of Asimina angustifolia from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Slimleaf Pawpaw

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Asimina longifolia Kral var. longifolia; Pityothamnus angustifolius (Rafinesque) Small[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

A description of Asimina angustifolia is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

It is found in southeastern Georgia to central peninsular of Florida to the west towards the Suwannee River.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Habitats include dry, well drained pinelands[1] and sandhills, flatwoods, roadsides, and scrub habitats in partial shade.[2][3] Specifically it is found in frequently burned longleaf pine-wiregrass uplands (Ultisols) and longleaf wiregrass sandhills (Entisols) in north Florida and southern Georgia. Asimina angustifolia is predominately in the native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of south Georgia. It was found to decrease its occurrence or become absent in respnse to soil disturbance by agricultural practices in southwest Georgia. It has also shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished pinelands that were disturbed by agriculture.[4] Additionally, A. angustifolia has been shown to be a deacreaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[5]

Associated species includes Phlox floridana, Stillingia sylvatica, Lactuca graminifolia, Stylosanthes biflora, Erigeron strigosa, Baptisia lanceolata, Hedyotis crassifolia, Pterocauloon undulatum, Asclepias humistrata, Quercus hemisphaerica and others.[3]

Phenology

A. angustifolia flowers from spring to summer and has been observed to flower in January and May to July in north Florida.[2][6]

Kevin Robertson has observed this species flower within three months of burning. KMR

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates. [7]

Fire ecology

This species has been seen in burned and fire excluded areas[3] and resprouts and flowers within two months of burning. KMR Populations of Asimina angustifolia have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[8]

Herbivory and toxicology

It consists of 2-5% of diet for small mammals and terrestrial birds.[9] For humans, the fruit is edible, like a cucumber, with a fine hard pulp that is yellow inside.[10] The plant also serves as a host for the Zebra Swallowtail Butterfly, and it is seasonally consumed by gopher tortoises.[11]

Diseases and parasites

Susceptible to leaf blotch, eye spot, and other fungal diseases.[12]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

A. angustifolia should avoid soil disturbance by agriculture to conserve its presence in pine communities.[4] It requires frequent fire and protection from soil disturbance.

Cultural use

The fruit of A. triloba is known to be sweet and custard-like. It was often used in baking, pie filling, or eaten raw. The fruits fall from the tree early and must be harvested from the ground to ripen later.[13] For medicinal purposes, the seeds can be used to induce vomiting or to treat head lice when powdered, and the fruit juice can be a treatment for intestinal worms.[14] Caution should be exercised though, as some people exhibit an allergic reaction of dermatitis to the fruit.[15]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wunderlin, Richard P. and Bruce F. Hansen. Guide to the Vascular Plants of Florida. Third edition. 2011. University Press of Florida: Gainesville/Tallahassee/Tampa/Boca Raton/Pensacola/Orlando/Miami/Jacksonville/Ft. Myers. 258. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: L. C. Anderson, R. K. Godfrey, R. Komarek, A. Schmidt, and Robert S. Blaisdell. States and Counties: Florida: Gadsden, Lafayette, Leon, and Wakulla. Georgia: Baker and Thomas.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 7 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Rafinesque, C. S. (1828). Medical flora; or Manual of the medical botany of the United States of North America.

- ↑ Denhof, Carol. 2013. Understory Plant Spotlight Slimeleaf Pawpaw Asimina angustifolia Raf. The Longleaf Leader. Vol. VI. Iss. 2. Page 8

- ↑ [[1]]Garden Geek. Accessed: March 31, 2016

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.

- ↑ Burrows, G.E., Tyrl, R.J. 2001. Toxic Plants of North America. Iowa State Press.