Stylosanthes biflora

| Stylosanthes biflora | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Michelle M. Smith | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta – Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Stylosanthes |

| Species: | S. biflora |

| Binomial name | |

| Stylosanthes biflora (L.) Britton, Sterns & Poggenb. | |

| |

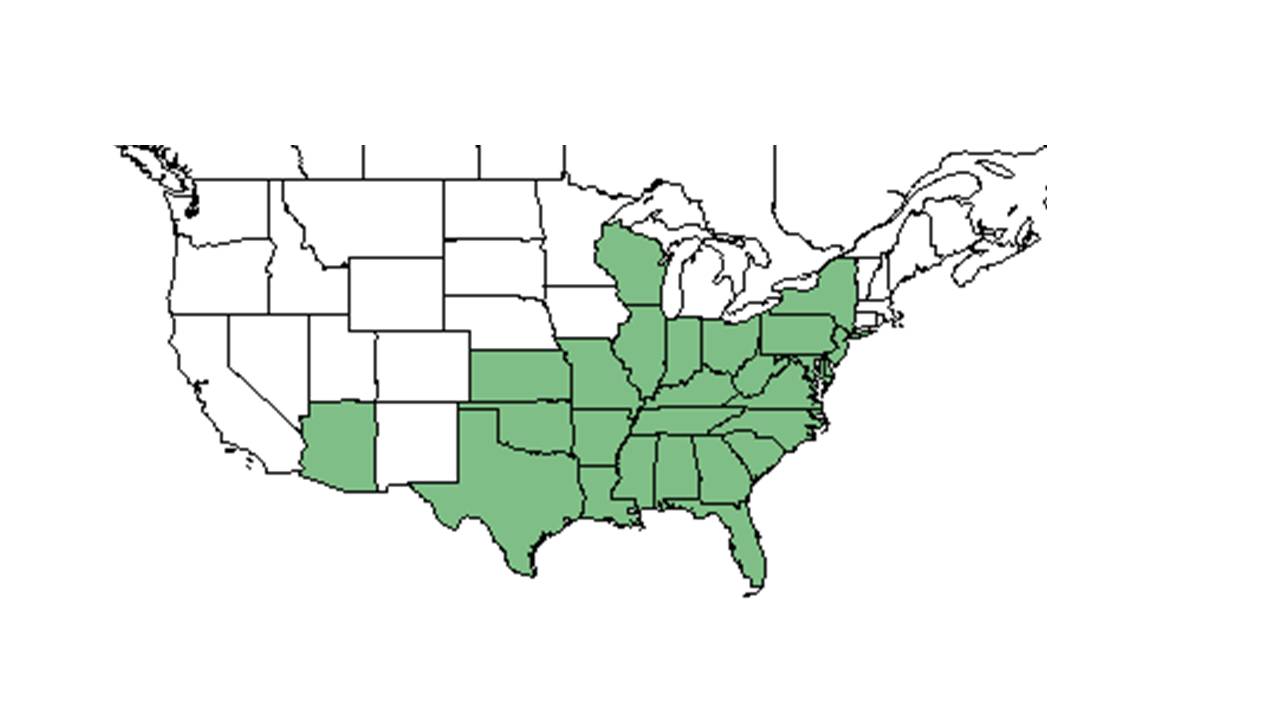

| Natural range of Stylosanthes biflora from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Sidebeak pencilflower

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: S. riparia Kearney; S. riparia var. setifera Fernald.[1]

Variations: S. biflora var. hispidissima (Michaux) Pollard & Ball.[2]

Description

"Prostrate to erect, perennial herb, stems few to many, 1-5 dm long, glabrate to bristly-hirsute. Leaves pinnately 3-foliolate; leaflets elliptic to oblanceolate, 1.5-4 cm long, entire, estipellate; stipules striate, finely pubescent to bristly hirsute, subulate, (0.4) 1-1.5 cm long, aristately tipped. Hypanthium pedicel-like, glabrous, 3-4 mm long. Calyx glabrous, tube short, campanulate above the filiform hypanthium, upper 2 lobes united, obtuse, 1.2-1.8 mm long, the 2 lateral lobes oblong, obtuse, ca. 1 mm long, the lowermost lobe acute, ca. 2 mm long; petals orange-yellow to whitish, standard 5-9 mm long; stamens 10, monadelphous, anthers alternating between oblong and subglobose. Legume short-pubescent, obliquely ovate, 3-5 mm long, sessile, reticulate, usually only the upper segment maturing, the lower pedicel-like." [3]

The root system of Stylosanthes biflora includes root tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[4]. Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 283.6 mg/g (ranking 14 out of 100 species studied).[4]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Stylosanthes biflora has root tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 3.08 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 283.6 mg g-1.[5]

Distribution

Ecology

It is a legume. [6]

Habitat

S. biflora has been found in pine-oak flatwoods, longleaf pine-scrub oak ridges, turkey oak forests, and open oak-scrub woodland.[7] It is also found in disturbed areas including along roadways, fallow fields, pastures, and burned longleaf pine flatwoods.[7][8]

Associated species: Centrosema, Conradina verticillata, Lespedeza, Phlox floridana, Stillingia sylvatica, Asimina longiflolia var. spathulata, Lactuca graminifolia, Stylosanthes biflora, Erigeron strigosa, Baptisia lanceloata, Hedyotis crassifolia, Tercauloon undulatum, Asclepias humistrata, Quercus hemisphaerica, Pinus palustris, Panicum, Andropogon, and Toxicodendron.[8][9][10][11]

It can additionally be found in xeric areas, [12] and S. biflora can survive in disturbed areas.[13] In Baker County, Georgia at Jones Ecological Research Center with native groundcover managed with frequent fire.[14][15] It is common in longleaf pine communities.[12] Hainds and his team found that S. biflora occurred in 92.3% of the plots.[16] Longleaf pine flatwoods that are mesic, fire-maintained savannas or sparse woodlands with nutrient-poor soils.[17] Longleaf pine stands that originated from seed in Rapides Parish, Louisiana that have fine sandy loam soils.[18] In Buettner Xeric Limestone Prairies in Monroe County, Illinois they have outcrops along streams and river where a prescribed burn was conducted in the nearby woody area in 2010.[19]

S. biflora became absent in response to military training in west Georgia longleaf forests.[20] It also decreased its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia.[21]

S. biflora does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[22]

Stylosanthes biflora is frequent and abundant in the Panhandle Xeric Sandhills, North Florida Subxeric Sandhills, Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands, and Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[23]

Phenology

S. biflora has observed flowering and fruiting from April to December with peak inflorescence in May.[8][24] It has a mid-summer flowering peak.[6] Following a lightning-season burn, it continues to reproduce through late summer and fall.[6]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[25]

Fire ecology

Populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns,[26][27] as Stylosanthes biflora seems to thrive under frequent burning around the summertime. A study describing the effects of a seasonal fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas found that the number of flowers produced was greatest after a lightning-season burn (26.8), with less flowers being produced after a late winter/early spring burn (16.2) and after instances of no burning (15.4).[28] This study also found that the duration of synchronous flowering was greatest after a late winter/early spring burn (174.3 days) and decreased in duration after an instance of no fire (153.3 days) and after a lightning-season burn (89.3 days).[29] Additionally, the peak flowering activity occurred earliest after an instance of no fire (199.7 Julian), with peak flowering occurring later after a late winter/early spring burn (216.7 Julian) and after a lightning-season burn (265.7 Julian).[30] Density of S. biflora was greater after frequent late dormant-season fires.[31] S. biflora was found only in annual winter and annual summer long-term (20 years) burned loblolly pine plots, and even then, only rarely.[32]

Herbivory and toxicology

Gopher tortoises (Gopherus polyphemus) graze on Stlosanthes bioflora.[14]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 604. Print.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Hiers, J. K., R. Wyatt, et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, and Nancy E. Jordan. States and counties: Florida: Escambia, Lafayette, Leon, Liberty, and Wakulla.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: August 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Lisa Keppner, Ed Keppner, Nancy E. Jordan, Gary R. Knight, Robert K. Godfrey, F. S. Earle, C. F. Baker, S. W. Leonard, Gwen Roney, C. Jackson, Robert Kral, Mabel Kral, Gwynn W. Ramsey, Richard S. Mitchell, O. Lakela, D. B. Ward, L. J. Brass, Robert L. Lazor, Jean W. Wooten, S. C. Hood, R. C. Phillips, William Reese, Paul Redfearn, Leon Neel, R. Komarek, R. A. Norris, Andre F. Clewell, Chris Cooksey, M. Davis, Cecil R Slaughter, Peter H. Raven, Tamra Engelhorn Raven, C. L. Huff, C. Ritchie Bell, James W. Hardin, Wilbur H Duncan, Effie Boon, M. Morgan, R. L. Wilbur, H. K. Svenson, A. B. Seymour, D. S. Correll, H. B. Correll, H. R. Reed, Delzie Demaree, I. M. Johnston, G. Edwin, L. J. Uttal, Norlan C. Henderson, L. B. Smith, A. R. Hodgdon, M. A, Chrysler, S. J. Ewer, Roy Hood, R. D. Houk, Kurtz, Angus Gholson, Jr., David M. DuMond, Clarke Hudson, John W. Thieret, S. B. Jones, Bob Mills, Champ Clark, Sidney McDaniel, Samuel B. Jones, Jr., James G. Teer, Roomie Wilson, P. L. R., Elizabeth Ann Bartholomew, Edward S. Steele, Duane Isely, A. J. Sharp, S.M. Tracy, F. H. Sargent, W. W. Ashe, David Moreland, John R. Wood. States and Counties: Alabama: Clarke, Covington, Cullman, Escambia, Henry, Lee. Arkansas: Columbia, Hot Spring, Logan, Pulaski, Saline. Florida: Bay, Citrus, Duval, Escambia, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Hillsborough, Jackson, Jefferson, Lafayette, Leon, Liberty, Okaloosa, Putnam, Suwannee, Taylor, Wakulla, Walton, Washington. Georgia: Decatur, Grady, Johnson, Mitchell, Rabun, Seminole, Taylor, Thomas, Toombs. Illinois: Lawrence. Kansas: Montgomery. Louisiana: Bienville, Claiborne, Natchitoches, Tangipahoa. Mississippi: Amite, Covington, Harrison, Jackson, Jones, Lamar, Marion, Panola. Missouri: Benton, Carter, Dallas, Dent, Jefferson, McDonald, Ozark, Polk, St Clair. New Jersey: Atlantic. North Carolina: Burke, Catawba, Craven, Guilford, Iredell, Lee, Warren. South Carolina: Oconee, Union. Tennessee: Bledsoe, Coffee. Texas: Brazos, Harris, Morris, Shelby, Walker. Virginia: Dinwiddie, Greensville, Henry, Montgomery, Prince William, Roanoke, Rockingham. West Virginia: Wirt.

- ↑ Auburn University, John D. Freeman Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: States and Counties: Alabama: Russell.

- ↑ Austin Peay State University Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Matt Bruton, Dwayne Estes, and Kim Norton. States and Counties: Tennessee: Cumberland.

- ↑ California Botanic Garden Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: E. L. Richards. States and Counties: Arkansas: Poinsett.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Carter, R. E., M. D. MacKenzie, et al. (2004). "Species composition of fire disturbed ecological land units in the Southern Loam Hills of south Alabama." Southeastern Naturalist 3: 297-308.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. K., K. L. Coffey, et al. (2004). "Ground cover recovery patterns and life-history traits: implications for restoration obstacles and opportunities in a species-rich savanna." Journal of Ecology 92: 409-421.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Birkhead, R. D., C. Guyer, et al. (2005). "Patterns of folivory and seed ingestion by gopher tortoises (Gopherus polyphemus) in a southeastern pine savanna." American Midland Naturalist 154: 143-151.

- ↑ Simkin, S., W. Michener, et al. (2001). "Plant Response Following Soil Disturbance in a Longleaf Pine Ecosystem." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 128(3): 208-218.

- ↑ Hainds, M. J., R. J. Mitchell, et al. (1999). "Distribution of native legumes (Leguminoseae) in frequently burned longleaf pine (Pinaceae)-wiregrass (Poaceae) ecosystems." American Journal of Botany 86: 1606-1614.

- ↑ Brewer, J. S. and S. P. Cralle (2003). "Phosphorus addition reduces invasion of a longleaf pine savanna (southeastern USA) by a non-indigenous grass (Imperata cylindrica)." Plant Ecology 167: 237-245.

- ↑ Haywood, J. D., A. Marti, et al. (1998). Seasonal biennial burning and woody plant control influence native vegetation in loblolly pine stands. Research Paper SRS-14. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service.

- ↑ McClain, W. E. and J. E. Ebinger (2014). "Vascular Flora of Buettner Xeric Limestone Prairies, Monroe County, Illinois." Southern Appalachian Botanical Society.

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 14 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Hiers, J. K., et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.

- ↑ Hiers, J. K., et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.

- ↑ Hiers, J. K., et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.

- ↑ Sparks, J. C., R. E. Masters, et al. (1998). "Effects of late growing-season and late dormant-season prescribed fire on herbaceous vegetation in restored pine-grassland communities." Journal of Vegetation Science 9: 133-142.

- ↑ Lewis, C. E. and T. J. Harshbarger (1976). "Shrub and herbaceous vegetation after 20 years of prescribed burning in the South Carolina coastal plain." Journal of Range Management 29: 13-18.