Conoclinium coelestinum

| Conoclinium coelestinum | |

|---|---|

| |

| photo by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Conoclinium |

| Species: | C. coelestinum |

| Binomial name | |

| Conoclinium coelestinum (L.) DC. | |

| |

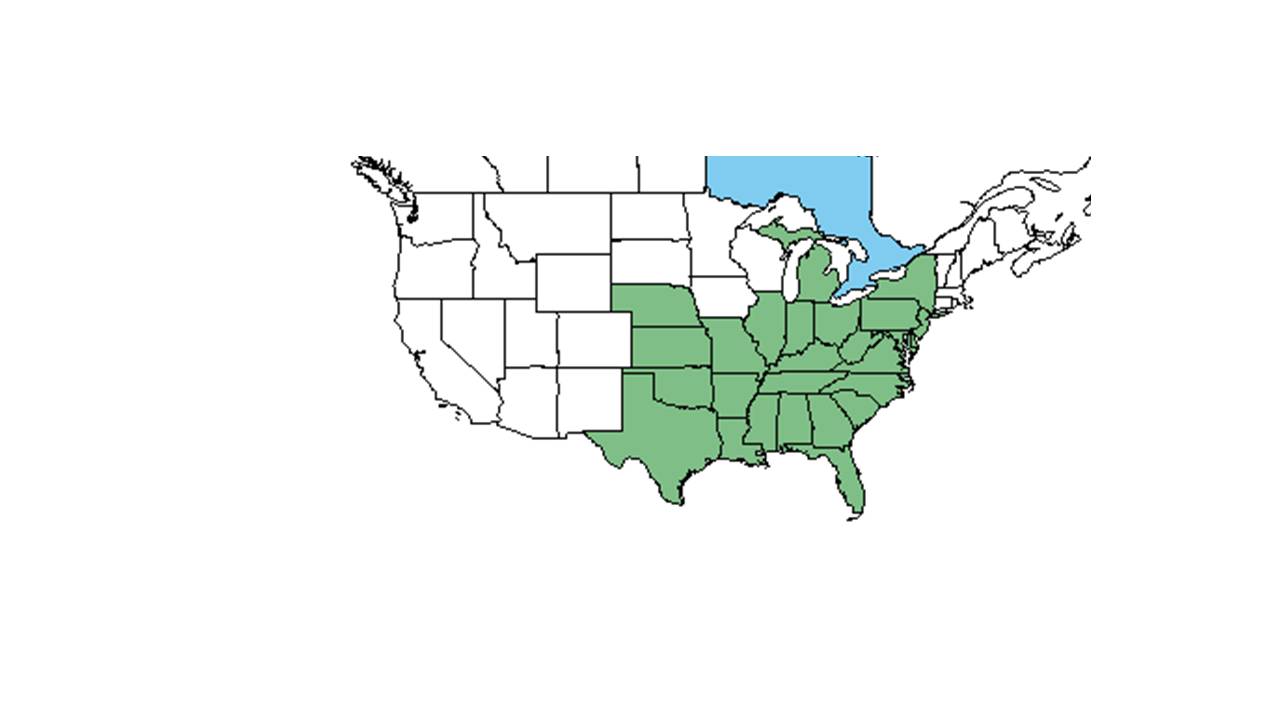

| Natural range of Conoclinium coelestinum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: mistflower, blue mistflower, ageratum

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

A description of Conoclinium coelestinum is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

Distributed from New Jersey, west to Wisconsin and Kansas, and south to Texas and Florida.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

This species has been observed growing in dry woods, hammocks, along the edges of river banks, floodplains, and streams, slash pine-palmetto woodlands, and pine woodlands. It is also found in areas disturbed by humans such as roadsides, ditches, and clearings. Thriving in light from shade to full sun, this species grows in moist sands or drying loamy sands and has even been recorded to grow in water along edges of springs.[3] C. coelestinum became absent in response to military training in west Georgia. It has also shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine forests that were disturbed by military training.[4] However, it was found to be neutral in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances, but an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[5]

Associated species include oak, beech, cypress, slash pine, saw palmetto, sweetgum, Cyrilla, Pinus taeda, Pinus echinata, Quercus nigra, Trichostema dichotomum, Helianthus angustifolius, Agaratina aromatica, Solidago odora, S. nemoralis, Pityopsis aspera var. adenolepis, Sorghastrum nutans, Andropogon virginicus var. virginicus, Chamaecrista fasciculata, Chamaecrista nictitans, Eupatorium hyssopifolium, Liatris graminifolia, Rubus cuneifolius,[3] and Hibiscus grandiflorus[6]

Phenology

C. coelestinum has been observed flowering from June through January with peak inflorescence in October.[3][7] Spreads by long, underground rhizomes.[8]

Seed dispersal

Seeds are dispersed by wind.[2]

Fire ecology

This species can grow in areas that are regularly burned[3] as shown by populations of Conoclinium coelestinum that are known to persist through repeated annual burning.[9]

Herbivory and toxicology

Conoclinium coelestinum has been observed to host whiteflies such as Trialeurodes sp. (family Aleyrodidae), leafcutting bees such as Megachile mendica (family Megachilidae), plant bugs such as Lygus lineolaris (family Miridae), leafhoppers from the familly Cicadellidae such as Empoasca sp. and Scaphytopius sp., treehoppers from the family Membracidae such as Acutalis tartarea and Entylia carinata.[10] Caterpillars of the moths Haploa clymene, Phragmatobia lineata, Carmenta bassiformis, and Schinia trifascia eat on the foliage.[8] The bitter foliage defers mammalian herbivores.

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

C. coelestinum should avoid soil disturbance by military training to conserve its presence in pine communities.[4]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 [[1]]Floridata. Accessed: April 14, 2016

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Ed Keppner, Lisa Keppner, Loran C. Anderson, K. Craddock Burks, Gary R. Knight, Sidney McDaniel, Robert K. Godfrey, Richard S. Mitchell, Kurt E. Blum, J. P. Gillespie, R. Kral, C. Jackson, R. E. Perdue, Jr., James D. Ray, Jr., Olga Lakela, Gwynn W. Ramsey, Dale Samler, Ronald A. Gursell, P. L. Redfearn, Jr., Brenda Herring, Joyce Leiper, A. F. Clewell, W. G. D'Arcy, Robert L. Lazor, V. Sullivan, Bruce Hansen, JoAnn Hansen, D. C. Hunt, R. Komarek, Angela M. Reid, and K. M. Robertson. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Brevard, Broward, Columbia, Dade, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Hamilton, Holmes, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Martin, Okaloosa, Sumter, Suwannee, Wakulla, and Washington. Georgia: Grady and Thomas.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Observation by Jake Antonia Heaton in Everglades National Park, Miami-Dade County, FL, June 12, 2016, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group June 12, 2016.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 8 DEC 2016

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 [[2]]Illinois Wildflowers. Accessed: April 14, 2016

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [3]