Chamaecrista nictitans

| Chamaecrista nictitans | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John R. Gwaltney, Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Chamaecrista |

| Species: | C. nictitans |

| Binomial name | |

| Chamaecrista nictitans (L.) Moench | |

| |

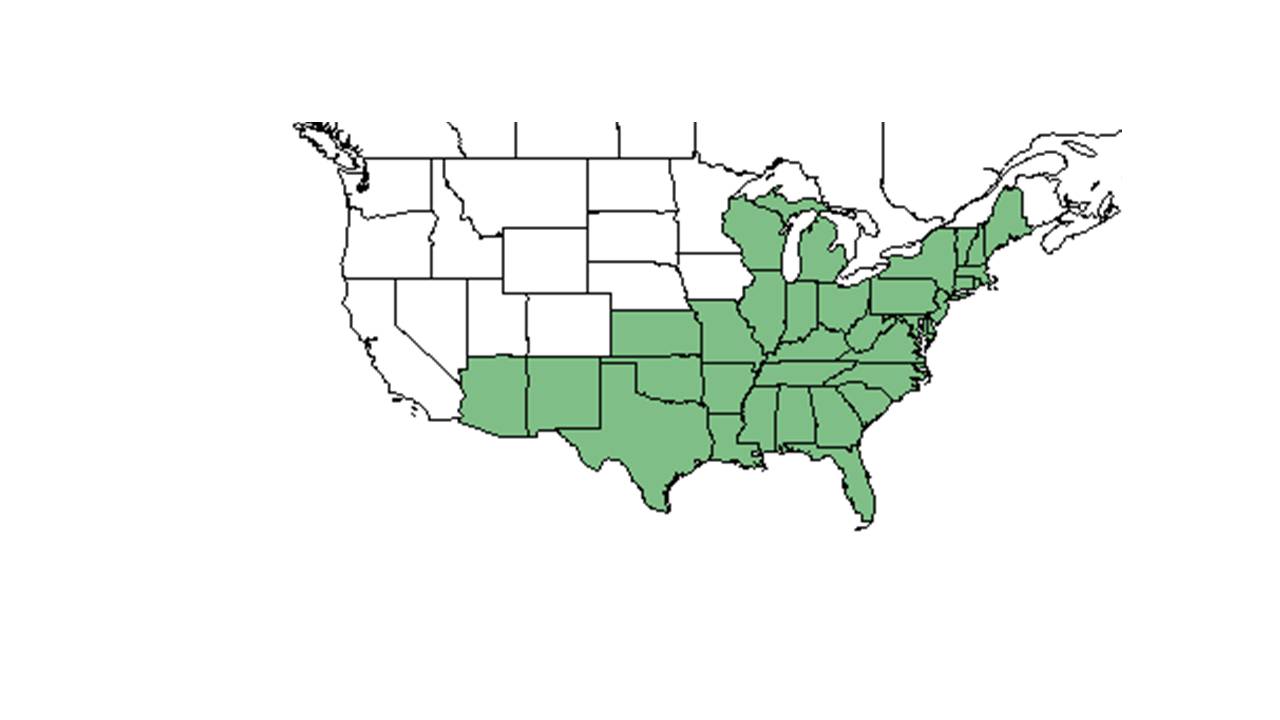

| Natural range of Chamaecrista nictitans from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Sensitive Partridge Pea; Common Sensitive-plant

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Cassia aspera Muhlenberg ex Elliott; Chamaecrista aspera (Muhlenberg ex Elliott) Greene; Cassia nictitans Linnaeus; Chamaecrista procumbens (Linnaeus) Greene; Chamaecrista multipinnata Pollard.[1]

Varieties: Chamaecrista nictitans (Linnaeus) Moench var. aspera; Chamaecrista nictitans (Linnaeus) Moench var. nictitans.[1]

Description

Generally, the Chameacrista genus includes trees, shrubs, or herbs. The leaves are evenly pinnate with conspicuous gland(s) on the petiole or rachis. The perfect (bisexual) flowers are either solitary or clustered in axillary racemes or terminal panicles. The calyx has an inconspicuous tube, 5 lobes, equally imbricate, and often unequal. There are 5 petals and are a little unequal. The 5 - 10 stamens, are often unequal and some are sterile or imperfect. The anthers are attached at the base and open by 2 apical pores. The legume is few to many-seeded, often septate, and exceedingly variable.[2]

Specifically, Chamaecrista nictitans is an annual decumbent herb that grows between 10 - 50 cm from the taproot and forms large mats. The stems are glabrous to densely pubescent with incurved trichomes. The leaves are sensitive with a slender-stalked and umbrella-shaped gland about 0.4 - 0.8 mm in diameter. Just below the leaves are persistent striate. The axillary flowers are solitary or 2 - 3 borne in a short raceme. The pedicels grow up to 1 - 4 mm long. The sepals are lanceolate acuminate in shape and grow 3 - 4 mm long. The petals are bright yellow in color, very unequal, and the lowermost and largest is 6 - 8 mm long and about 2 times as large as the other four. There are 5 unequal stamens. The legume is elastically dehiscent, growing 2 - 4 cm long, 3 - 6 mm broad, and is glabrous to most commonly densely pubescent or rarely shaggy. [2]

Distribution

C. nictitans is widely distributed in the United States from Maine down the east coast to Florida, Michigan and Wisconsin, Kansas and Missouri, and as far west as New Mexico and Arizona.[3] It is also native to Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, Navassa Island, Mexico and portions of Central and South America, and introduced to Hawaii and the Pacific Basin as well as subtropics and tropics in Asia.[3][4]

C. nictitans var. nictitans is more widely distributed in North America and into South America while C. nictitans var. aspera can be found from southeast South Carolina to south Florida[5] and the Bahamas.[6]

Ecology

It is a legume. By mid-season in June and July, a maximum nitrogen-fixing rate was observed.[7]

Habitat

C. nictitans is tolerant of overstory canopies that decrease the light level to about half the ambient (i.e., it can live in partially shaded areas and its nitrogen-fixing capability won't be significantly affected).[7] It is also tolerant of a wide range of dry to wet soil types, having been found in soils as diverse as sandy silt loam, low black sandy peat, shallow soil overlaying limerock, shell sand, red clay, loessial soil, sandy clay loam, dry marl, calcareous and shaly soils, clay, igneous intrusive rocky soils, and novaculite ridges.[8]

As a result of its impressive tolerance, C. nictitans occurs in a variety of natural and disturbed communities such as longleaf pine-wiregrass communities,[7] longleaf pine-scrub oak sandy ridges, annually burned savannas, xeric oak-saw palmetto scrub communities, wooded banks of creeks, slash pine flats, borders of brackish and salt marshes, low weedy swales, laurel oak woodlands, upland slopes, dry sandhills, margins of hillside bogs, loblolly pine forests,[8] C. nictitans roadsides, railways, clear-cut pine flatwoods, vacant lots, cultivated fields, power line corridors, old fields, and plantations of young slash pine.[8]

It has shown regrowth in reestablished longleaf pinelands that were disturbed by agricultural practices in South Carolina, making it a post-agricultural woodland indicator species[9][10]; however, it has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished longleaf pinelands that were disturbed by agriculture in North Carolina.[9] C. nictitans exhibited its highest density in response to double disking in southern Georgia and has also shown positive regrowth in reestablished native habitat that was disturbed by disking.[11] Additionally, C. nictitans has increased in occurrence and abundance in response to clearcutting and chopping in South Carolina, and shown regrowth in reestablished native forests that were disturbed by clearcutting and chopping practices.[12] Furthermore, C. nictitans was shown to be an increaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances, but neutral in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[13]

Chamaecrista nictitans is frequent and abundant in the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands and Upper Panhandle Savannas community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[14]

Associated species include Chamaecrista fasciculata, Panicum sp., Andropogon sp., Strophostyles leiosperma, Quercus sp., Serenoa repens, Pinus elliottii, Pinus taeda, Pinus palustris, Gordonia lasianthus, Schizachyrium scoparium, and Sorghastrum nutans.[8][15]

Phenology

It has been observed flowering in August through October with peak inflorescence in September, and fruiting in August through November.[8][16]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates. [17]

Seed bank and germination

For propagation, the seeds need scarification for successful germination. It has best results when boiled between 70 and 80 degrees Celsius, and seedlings can germinate within 6 weeks.[15]

An early 2000s study found that while C. nictitans is found in the seed beds of old agricultural field soils, it is absent from the seed banks in flatwoods soils.[18]

Fire ecology

This species occurs in areas that regularly burn, suggesting a level of fire tolerance.[8] Populations of C. nictitand have been known to persist through repeated annual burns[19][20] and has been observed to colonize an area post burn where it was either absent or rare before the fire disturbance.[21]

A study found that C. nictitans benefited from winter and spring season burns rather than summer burns.[22] An additional study describing the effects of a seasonal fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas found that C. nictitans produced the greatest number of flowers after an instance of no fire (35.3) with the number decreasing slightly after a late winter/early spring burn (26.9) and dropping significantly after a lightning season burn (7.7).[23] The season of burning or presence of burning was not found to greatly impact the duration or timing of the synchronous peak for this species.[24]

Pollination

Chamaecrista nictitans has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host sweat bees such as Augochloropsis sumptuosa (family Halictidae)[25] It has also been observed to host sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Augochloropsis anonyma and A. aurata.[26][27]

Herbivory and toxicology

This species is not usually desired for grazing since it is slow to decompose, slow-growing, and can contain some toxicity. However, it is used for forage or hay in infertile subtropical soils, and is normally eaten by goats. C. nictitans is a great cover crop since it has the ability to build the nitrogen pool, organic matter in the soil, and increase overall availability of nitrogen. It is eaten by a variety of animals including eastern meadow lark, eastern mourning dove, bobwhite quail, and eastern turkey. The extrafloral nectaries on the plant attract spiders, ants, and pollinators. As well, it is a larval host for the little sulphur (Eurema lisa) and cloudless sulphur (Phoebis sennae) in the Lepidoptera order.

Diseases and parasites

C. nictitans is susceptible to nematodes, including Meloidogyne arenaria, M. incognita, and M. javanica.[28]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

C. nictitans can be considered weedy since it has the ability to easily spread to nearby fields, and especially in places where other competition is removed. For management of keeping the species, mowing off the other grasses and weeds that can outcompete C. nictitans along with lightly disking fields can alleviate this problem.[15]

Cultural use

Historically, the Cherokee Native American tribe utilized the species along with Cassia marilandica to be used to treat spasms in infants.[15] It was also used medicinally as a cathartic (helping bowel movements) and a vermifuge (expel worms).[29]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 577-8. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 5 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Cook, B.G., B.C. Pengelly, S.D. Brown, J.L. Donnelly, D.A. Eagles, M.A. Franco, J. Hanson, B.F. Mullen, I.J. Partridge, M. Peters, and R. Schultze-Kraft. 2005. Tropical forages: an interactive selection tool. Chamaecrista nictitans. CSIRO, DPI&F(Qld), CIAT, and ILRI, Brisbane, Australia. http://www.tropicalforages.info/key/Forages/Media/Html/Chamaecrista_nictitans.htm (accessed 03 Mar. 2015).

- ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ Sorrie, B. A. and A. S. Weakley 2001. Coastal Plain valcular plant endemics: Phytogeographic patterns. Castanea 66: 50-82.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Cathey, S. E., L. R. Boring, et al. (2010). "Assessment of N2 fixation capability of native legumes from the longleaf pine-wiregrass ecosystem." Environmental and Experimental Botany 67: 444-450.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Robert K. Godfrey, R. Komarek, R. F. Doren, Cecil R Slaughter, R. Kral, P. O. Schallert, S. M. Tracy, D. B. Ward, D. Burch, J. K. Small, Chas. A. Mosier, Richard D. Houk, A. H. Curtiss, O. Lakela, J. K. Small, G. K. Small, George R. Cooley, Richard J. Eaton, James D. Ray, Jr., C. Ritchie Bell, Loran C. Anderson, Neal Morar, Delzie Demaree, J. J. Rudloe, C.M. Rogers, J. Beckner, J. Carmichael, James R. Burkhalter, Robert L. Lazor, Sidney McDaniel, John Morrill, P. Gillespie, Richard S. Mitchell, W. D. Reese, Joseph Ewan, H. R. Reed, W. R. Anderson, M.N. Sears; Windler, Keenan, - Lombardo, - Williams; R. L. Lane, JR., J. B. Lewis, C. F. Hyams, S. B. Jones, Samuel B. Jones, Jr., John W. Thieret, William B. Fox, Louis Williams, R. L. Wilbur, Edward S. Steele, Robert F. Thorne, Geo M. Merrill, J.B. Norton, Harry E. Ahles, and R.S. Leisner. States and Counties: Alabama: Dale and Sumter. Arkansas: Conway, Garland, Hot Spring, Jefferson, Lee, Pope, Pulaski, and Sebastian. Dist of Columbia: Addison Hts. Florida: Alachua, Baker, Bay, Brevard, Calhoun, Collier, Dade, Dixie, Duval, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Hamilton, Hillsborough, Jackson, Jefferson, Lee, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Manatee, Marion, Monroe, Nassau, Okaloosa, Orange, Osceola, Pinellas, Polk, Putnam, St Johns, Sarasota, Seminole, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, Walton, and Washington. Georgia: Decatur, Grady, Taylor, and Thomas. Louisiana: Evangeline, Iberia, and Ouachita. Maryland: Baltimore. Mississippi: Harrison, Lamar, Pearl River, and Saratoga-city. North Carolina: Alleghany, Bertie, Bladen, Buncombe, Burke, Caldwell, Carteret, Catawba, Cherokee, Davidson, Harnett, Haywood, Iredell, Jackson, Mitchell, Orange, Robeson, Swain, Vance, Wilkes, and Wilson. South Carolina: Beaufort, Cherokee, Colleton, Darlington, and Jasper. Tennessee: Anderson, Bedford, and Coffee. Virginia: Amelia, Brunswick, Giles, Prince Edward, Roanoke, and Southampton. West Virginia: Cabell.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Buckner, J.L. and J.L. Landers. (1979). Fire and Disking Effects on Herbaceous Food Plants and Seed Supplies. The Journal of Wildlife Management 43(3):807-811.

- ↑ Cushwa, C.T. and M.B. Jones. (1969). Wildlife Food Plants on Chopped Areas in Piedmont South Carolina. Note SE-119. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 4 pp.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Sheahan, C.M. 2015. Plant guide for sensitive partridge pea (Chamaecrista nictitans). USDA-Natural Resources Conservation Service, Cape May Plant Materials Center, Cape May, NJ.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 5 APR 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Jenkins, Amy Miller. Seed banking and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae in pasture restoration in central Florida. University of Florida. 2003.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Hutchinson, T. (2005). Fire and the herbaceous layer of eastern oak forests. F. S. United States Department of Agriculture, Northern Research Station: 136-149.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Hiers, J. K., et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.

- ↑ Hiers, J. K., et al. (2000). "The effects of fire regime on legume reproduction in longleaf pine savannas: is a season selective?" Oecologia 125: 521-530.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).

- ↑ Grundel, R., et al. (2011). "A survey of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of the Indiana Dunes and Northwest Indiana, USA." Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 84(2): 105-138.

- ↑ Quesenberry, K. H., et al. (2008). "Response of native southeastern U.S. legumes to root-knot nematodes." Crop Science 48: 2274-2278.

- ↑ Nickell, J. M. (1911). J.M.Nickell's botanical ready reference : especially designed for druggists and physicians : containing all of the botanical drugs known up to the present time, giving their medical properties, and all of their botanical, common, pharmacopoeal and German common (in German) names. Chicago, IL, Murray & Nickell MFG. Co.