Commelina erecta

| Commelina erecta | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Tom Miller, Apalachicola National Forest, FL | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida – Monocotyledons |

| Order: | Commelinales |

| Family: | Commelinaceae |

| Genus: | Commelina |

| Species: | C. erecta |

| Binomial name | |

| Commelina erecta L. | |

| |

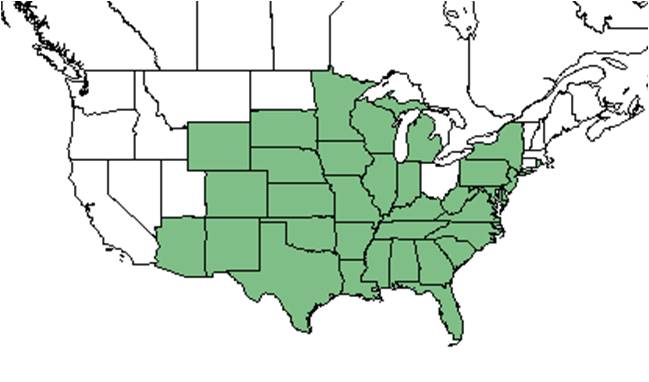

| Natural range of Commelina erecta from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: whitemouth dayflower, erect dayflower, sand dayflower, midwestern dayflower

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: C. erecta Linnaeus var. angustifolia (Michaux) Fernald; C. erecta Linnaeus var. erecta; C. erecta Linnaeus var. 'deamiana' Fernald; C. angustifolia Michaux; C. crispa Wooton[1]

Description

A description of Commelina erecta is provided in The Flora of North America.

In Collier County, FL, an albino form was observed.[2]

C. erecta var. angustifolia is a trailing plant that can have stems reach as long as 1.3 meters.[3] As a member of the Commelinaceae family, the genus name Commelina is named after the three Commelin brothers who were Dutch botanists, and this plant's two conspicuous petals are said to stand for the two brothers who were published while the third petal that is inconspicuous is said to represent the unpublished Commelin brother.[4]

The root system of Commelina erecta includes root tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[5]. Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 426 mg/g (ranking 1 out of 100 species studied).[5]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Commelina erecta has root tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 1.24 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 426 mg g-1.[6]

Distribution

In general, C. erecta is distributed across most of the continental United States, from New York and along the east coast south to Florida, west to South Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado, and Arizona. It is also native to Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.[7] C. erecta var. angustifolia is distributed from east North Carolina to south Florida, as well as Texas, Iowa, northwest Nebraska, New Mexico, and Colorado. However, C. erecta var. erecta is distributed from Pennsylvania to Missouri and east Kansas to Florida and Texas.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

In general, this species can grow in a wide range of habitats, including prairies, streambanks, gardens, roadsides, and places of waste.[4] C. erecta var. angustifolia can be found in sandhills and other sandy dry sites, dunes and sand flats on barrier islands, and shale barrens and other rocky areas. C. erecta var. erecta can be found in streambanks, woodlands and dry openings, riverbanks, and mesic forests.[3] Overall, this species can be seen as a dry to mesic species across its wide native range, since it is listed as a facultative, facultative upland, and obligate upland species that can occur in non-wetlands mostly but also wetland communities.[7] C. erecta has been observed in pine flatwoods, edges of cypress wetlands, along trails, open coastal hammocks, mixed hardwood forests, longleaf pine and scrub sandhill, steep slopes, limestone glades, and exposed lake beds.[8] It can grow on a variety of soils between sandy and clayey soils.[4] C. erecta has shown regrowth in reestablished longleaf pinelands that were disturbed by agricultural practices in South Carolina, making it a post-agricultural woodland indicator species.[9] C. erecta was found to be neutral in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[10]

Commelina erecta is an indicator species for the Panhandle Xeric Sandhills community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[11]

Associated species include Bulbostylis sp., Marsilea sp., Pinus elliottii, Pinus palustris, Desmodium ochroleucum, Rhynchosia sp., Ludwigia americana, Lindernia crustacea, Sesbania vesicaria, Quercus stellata, Quercus elliottii, and Aristida beyrichiana.[8]

Phenology

C. erecta has been observed flowering from May to November with peak inflorescence in June and July.[12][3] In repeated annual censuses conducted in October in permanently marked plots in native longleaf pine-wiregrass communities in southern Georgia, C. erecta appeared only in certain years, seemingly in particularly wet years, and was fairly common in the years that it appeared.[13] While each individual flower only blooms for a day, there are several buds on the plant that flower between 3 and 4 days apart from one another.[14]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. [15]

Seed bank and germination

In a greenhouse germination study, a success of 87% was found with twelve hours of daylight with temperatures between 75 and 85 degrees Fahrenheit and twelve hours of darkness with temperatures between 50 and 60 degrees Fahrenheit.[4]

Fire ecology

Populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns,[16][17] and C. erecta has been observed in a slash pine-palmetto community that was burned, and was observed to flower in August after a burn in May of the same year.[8] Multiple studies have found the plant to increase in frequency in response to fire.[18][19] Another found a winter burn in January to greatly increase the frequency of C. erecta by April of that year, but to decrease in frequency by June.[20]

Pollination

In Daytona Beach, FL, the pollen-feeding bee fly (Poecilognathus punctipennis) was observed visiting Commelina erecta[21] and performing their unique foraging behavior.[22] Several members of the Hymenoptera order were observed visiting flowers of C. erecta at the Archbold Biological Station, including leafcutting bees such as Megachile brevis pseudobrevis (family Megachilidae), and sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Augochlorella aurata, Augochloropsis metallica, A. sumptuosa, Lasioglossum nymphalis, and L. placidensis.[23] Other species in the Hymenoptera order observed to pollinate this species include Dialictus nymphalis and D. placidensis.[24]

Herbivory and toxicology

C. erecta consists of approximately 10-25% of the diet for large mammals, and 5-10% of the diet for terrestrial birds.[25] It is a preferred source of food for white-tailed deer, it is grazed by cattle, and the seeds are eaten by bobwhite quail, white-winged doves, and mourning doves.[4] Gopher tortoises (Gopherus polyphemus) have been observed to forage on the plant.[26]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

This species is listed as endangered by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and Energy, as threatened by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, as extirpated by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, and as probably extirpated by the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.[7] However, since the plant is weedy, it has the potential to become invasive in some areas.[14]

Cultural use

It is possible the plant's roots could be edible when cooked, but needs further investigation.[27]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Observation by Roger Hammer in CREW Marsh, Collier County, FL, May 23, 2017, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group May 23, 2017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Lloyd-Reilley, J. and E. Kadin. (2006). Plant Guide: Erect Dayflower Commelina erecta. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Kingsville, TX.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 15 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: March 2019. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Alice Bard, D. E. Breedlove, Steve Christman, Richard R. Clinebell II, M. Davis, J. Dwyer, J. Kevin England, Jamie England, Robert K. Godfrey, Dianne Hall, Ann F. Johnson, Ed Keppner, Lisa Keppner, R. Komarek, R. Kral, Robert M. Laughlin, J. R. Martinez, C. H. Mueller, C. Nelson, John B. Nelson, R. A. Norris, William Platt, Cecil R. Slaughter, L. B. Smith, Edwin L. Tyson, and F. Lyle Wynd. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Bay, Brevard, Calhoun, Duval, Franklin, Gadsden, Jackson, Jefferson, Lee, Leon, Okaloosa, St Johns, St Lucie, Volusia, Wakulla, and Washington. Alabama: Marengo. Georgia: Thomas. South Carolina: Richland. Texas: Smith.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 7 DEC 2016

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. 2017 Pebble Hill Fire Plots database. Tall Timbers Research, Inc., Tallahassee, Florida.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 15, 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Duncan, R. S., et al. (2008). "The effect of fire reintroduction on endemic and rare plants of a southeastern glade ecosystem." Restoration Ecology 16: 39-49.

- ↑ Ruthven III, D. C., et al. (2000). "Effect of Fire and Grazing on Forbs in the Western South Texas Plains." The Southwestern Naturalists 45(2): 89-94.

- ↑ Hansmire, J., et al. (1988). "Effects of Winter Burns on Forbs and Grasses of the Texas Coastal Prairie." The Southwestern Naturalists 33(3): 333-338.

- ↑ Observation by Peter May in Tiger Bay State Forest, Daytona Beach, FL, May 23, 2017, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group May 23, 2017.

- ↑ Deyrup MA (1988) Pollen-feeding in Poecilognathus punctipennis (Diptera: Bombyliidae). The Florida Entomologist 71(4):597-605.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).

- ↑ Everitt, J.H., D.L. Drawe, and R.I. Lonard. 1999. Field guide to the broad leaved herbaceous plants of South Texas used by livestock and wildlife. Texas Tech University Press. Lubbock.

- ↑ Carlson, J. E., et al. (2003). "Seed dispersal by Gopherus polyphemus at Archbold Biological Station, Florida." Florida Scientist 66: 147-154.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.