Ageratina aromatica

| Ageratina aromatica | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Ageratina |

| Species: | A. aromatica |

| Binomial name | |

| Ageratina aromatica (L.) Spach | |

| |

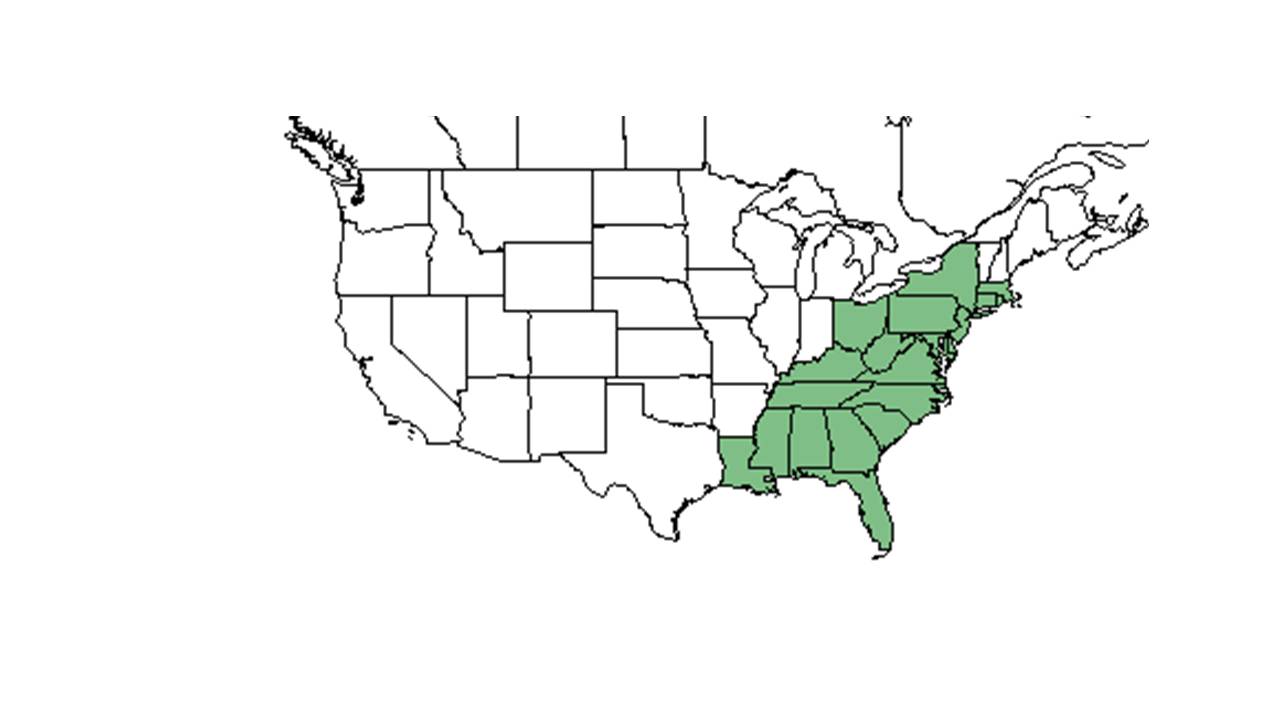

| Natural range of Ageratina aromatica from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Lesser snakeroot; Wild hoarhound; Small-leaved white snakeroot

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Eupatorium aromaticum Linnaeus[1]

Varieties: A. aromatica var. aromatica (L.) Spach; A. aromatica var. incisa (Gray) C.F. Reed; Eupatorium latidens Small[1]

The genus name Ageratina comes from the Greek word "agera" which means un-aging, not growing old in reference to the longevity of the flowers. The specific epithet comes from the Greek word "aroma" meaning spice seasoning.[2]

Description

A description of Ageratina aromatica is provided in The Flora of North America.

The lifepans of individual plants within the Wade Tract old-growth pine savanna in southern Georgia, based on multiple years of data from permanent plots, is several years, with genets that become established and flower persisting through 1 - several fires.[3] No genet has been observed to survive more than about 4-5 years.[4]

Ageratina aromatica genets commonly are comprised of a single ramet or a few ramets within a few centimeters of each other, especially after fires have top-killed existing ramets. Underground the roots radiate from the base of the ramet stem and are thickened relative to most fibrous roots of composites. Below ground rhizomes often are not present, but if present are short. The compact growth form of flowering snakeroots in the old-growth pine savanna, consisting of one or a few closely spaced above-ground ramets, may differ from growth forms of genets in more open secondary forests.[3]

It can be distinguished from the closely related A. altissima[1] by having smaller, thicker, and less sharply toothed leaves on shorter petioles, smaller stature, smaller flower heads, and thicker roots, and shorter, firmer pubescence.[4]

Distribution

It is found from eastern Louisiana and Mississippi eastward to the Atlantic coast and northward to Pennsylvania and Massachusetts.[5] It is regionally rare in New England. In Massachusetts and Connecticut it is listed as endangered (S1) and in Rhode Island is historical only (SH).[4]

Ageratina aromatica is among the 20 most frequent ground layer plant species in mesic old-growth pine savanna on the Wade Tract, occurring in almost half the permanent plots in the ongoing long-term study.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

A. aromatica can be found in a variety of longleaf pine communities, mixed pine-hardwood forests, open oak woods, live oak woodlands, upland woodlands, and rolling red hills. It can also be found in disturbed habitat such as roadsides, along fences, and on the edges of fields.[6]

On the Wade Tract, A. aromatica occurs in open pine savanna along mid and lower mesic slopes, but tends to be absent from drier, sandy ridges. It often occurs in slightly disturbed areas of the Wade Tract, and it occurs in natural hardwood thickets as well.[3] Ageratina aromatica is considered a dominant plant species in post-agricultural longleaf pine savannas.[7] This species is observed in a range of light conditions, from open forest situations to semi-shaded and shady areas. In the ground layer of pine savannas at Girl Scout Camp Whispering Pines in Louisiana, A. aromatica was neither positive nor negatively associated with understory light levels, suggesting broad tolerance of light conditions.[8] Additionally, a study exploring longleaf pine patch dynamics found A. aromatica to be most strongly represented within stands of longleaf pine that are between 10-130 years of age.[9] A. aromatica occurs most frequently in moist sandy loam, dry sand, and areas of lime rock.[6] A. aromatica became absent in response to soil disturbance by military training in west Georgia. It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished pinelands that were disturbed by this activity.[10] However, A. aromatica has been found to be an increaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances but neutral in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[11]

Ageratina aromatica is an indicator species for the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands and Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[12]

Associated species include Chamaecrista fasiculata, Eupatorium album, Helianthus angustifolius, Liatris graminifolia, Solidago odora, Sorghastrum nutans, Pinus palustris, Pinus echinata, Aristida beyrichiana, Quercus, Liatris, and Dicerandra species and others.[6]

Phenology

Flowering occurs in the fall[13], and has been observed flowering in the months of October, November, and January with peak inflorescence in October.[14] It has been observed to fruit in October and November as well.[6]

On the Wade Tract, flowering occurs at the end of the growing season, in the latter part of October and November, following spring fires. At this time, A. aromatica often is the most abundant and conspicuous flowering composite in the ground layer of mesic savanna. The white inflorescences are at "canopy" height of the herbaceous vegetation and form flat platforms of flowers visited by numerous bees and other flying insects in the late fall. Flowering may occur sporadically in years between fires, but is most noticeable as highly synchronized flowering displays across mesic landscapes on the Wade Tract following spring fires.[3]

In north Florida, it has been observed to reproduce with A. juncunda[2], suggesting that these species are possibly conspecific.[15]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind.[16]It can spread vegetatively in a limited area, but it is dependent on sexual reproduction to colonize new areas.[4]

On the Wade Tract, achenes are wind-dispersed in the late fall/early winter. The achenes are light, but the small pappus results in seeds that tend to fall within the vicinity of the parent plant.

Seed bank and germination

Whether a seed bank is present is not known, but if present, it is likely only to be comprised of short-lived seeds. Germination has been observed in burned areas during the early summer following the onset of summer rains. Seedlings sometime are numerous around established plants. Survival of seedlings is very low, but the seedlings appear to be shade tolerant and can persist under the shade of other ground-layer plants. Seedlings in plots on the Wade Tract have reached a size such that they flower within 2-3 years. Nonetheless, many juvenile plants survive for several years before being killed in fires without ever flowering. Populations of A. aromatica on the Wade Tract thus tend to be multi-sized, but the short lifespan results in fairly rapid turnover within small areas.[3]

Fire ecology

A. aromatica is found in annually burned savannas and wet pinelands[6] as shown in the populations occurring in annually burned research plots.[17][18] It a common ground cover species of North Florida Longleaf Woodlands, which are dependent on fire.[19] This species requires full to partial sun, such that forest canopy closure resulting from a lack of fire can shade out A. aromatica.[4]

The nature of the population dynamics of A. aromaticaon the Wade Tract suggests that this species should be sensitive to fire suppression and other disturbances that reduce numbers of established plants, but also capable of rapid recovery if some plants survive the disturbances.[3]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

In New England, it is threatened by fire suppression and lack of disturbance that allows for canopy closure and forest maturation, resulting in lack of sunlight needed for A. aromatica to prosper.[4] It is listed as endangered in the state of Massachusetts. [20]

This species should avoid soil disturbance by military training to conserve its presence in longleaf pine habitats.

Cultural use

The plant is antispasmodic, diaphoretic, diuretic and expectorant[21]. It is used in the treatment of inflammation and irritability of the bladder[22], ague, pulmonary diseases, stomach complaints and nervous diseases.[23][24]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ [[3]]Alabama Plants. Accessed: March 22, 2016

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 William J. Platt, Unpublished data from ongoing long-term study of ground layer vegetation on the Wade Tract

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 [[4]]New England Wild. Accessed: March 22, 2016

- ↑ Hall, David W. Illustrated Plants of Florida and the Coastal Plain: based on the collections of Leland and Lucy Baltzell. 1993. A Maupin House Book. Gainesville. 100. Print.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 .Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Robert Blaisdell, Andre F. Clewell, William B. Fox, J. P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, C. Jackson, Gary R. Knight, R. Komarek, Robert Kral, Robert L. Lazor, Sidney McDaniel, Richard S. Mitchell, P. L. Redfearn Jr., V. I. Sullivan, Jean W. Wooten, and Geo. Wilder MacClendons. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Holmes, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Okaloosa, Putnam, Santa Rosa, St. Johns, and Wakulla. Georgia: Grady.

- ↑ Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson (2007). A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, south Georgia, USA. Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, Tallahassee, Tall Timbers Research Station.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., S.M. Carr, M. Reilly, and J. Fahr. 2006. Pine savanna overstorey influences on ground-cover biodiversity. Applied Vegetation Science 9:37-50.

- ↑ Mugnani et al. (2019). “Longleaf Pine Patch Dynamics Influence Ground-Layer Vegetation in Old-Growth Pine Savanna”.

- ↑ (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Wunderlin, Richard P. and Bruce F. Hansen. Guide to the Vascular Plants of Florida. Second edition. 2003. University Press of Florida: Gainesville/Tallahassee/Tampa/Boca Raton/Pensacola/Orlando/Miami/Jacksonville/Ft. Myers. 295. Print.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 4 MAR 2019

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. and J. W. Wooten (1971). "A Revision of Ageratina (Compositae: Eupatorieae) from Eastern North America." Brittonia 23(2): 123-143.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., K. M. Robertson, et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ USDA Plants Database URL: https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=ANGE

- ↑ .Usher. G. A Dictionary of Plants Used by Man. Constable 1974 ISBN 0094579202

- ↑ Grieve. A Modern Herbal. Penguin 1984 ISBN 0-14-046-440-9

- ↑ Coffey. T. The History and Folklore of North American Wild Flowers. Facts on File. 1993 ISBN 0-8160-2624-6.

- ↑ Plants for a Future - Ageratina aromatica (L.) Spach URL: https://pfaf.org/User/Plant.aspx?LatinName=Ageratina+aromatica last accessed August 23, 2021.