Difference between revisions of "Chaptalia tomentosa"

HaleighJoM (talk | contribs) |

HaleighJoM (talk | contribs) (→Ecology) |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

The species could be hypothesized to be fire-tolerant since it is found in upper Florida panhandle savannas that are fire-dependent.<ref name= "Carr">Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.</ref> One study found ''C. tomentosa'' to significantly increase in frequency in response to a recent fire.<ref name= "Hinman">Hinman, S. E. and J. S. Brewer (2007). "Responses of Two Frequently-Burned Wet Pine Savannas to an Extended Period without Fire." The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 134(4): 512-526.</ref> As number of growing seasons since past fire disturbance increases, one study found ''C. tomentosa'' to decrease in ground cover and frequency over the years.<ref name= "Lemon">Lemon, P. C. (1949). "Successional responses of herbs in the longleaf-slash pine forest after fire." Ecology 30: 135-145.</ref> | The species could be hypothesized to be fire-tolerant since it is found in upper Florida panhandle savannas that are fire-dependent.<ref name= "Carr">Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.</ref> One study found ''C. tomentosa'' to significantly increase in frequency in response to a recent fire.<ref name= "Hinman">Hinman, S. E. and J. S. Brewer (2007). "Responses of Two Frequently-Burned Wet Pine Savannas to an Extended Period without Fire." The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 134(4): 512-526.</ref> As number of growing seasons since past fire disturbance increases, one study found ''C. tomentosa'' to decrease in ground cover and frequency over the years.<ref name= "Lemon">Lemon, P. C. (1949). "Successional responses of herbs in the longleaf-slash pine forest after fire." Ecology 30: 135-145.</ref> | ||

| − | ===Pollination and | + | <!--===Pollination===--> |

| + | |||

| + | ===Herbivory and toxicology===<!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | ||

It is considered to have poor forage value.<ref name= "Hilman">Hilman, J. B. (1964). "Plants of the Caloosa Experimental Range " U.S. Forest Service Research Paper SE-12 </ref> | It is considered to have poor forage value.<ref name= "Hilman">Hilman, J. B. (1964). "Plants of the Caloosa Experimental Range " U.S. Forest Service Research Paper SE-12 </ref> | ||

<!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | <!--===Diseases and parasites===--> | ||

Revision as of 12:23, 22 June 2022

| Chaptalia tomentosa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Katelin Pearson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Chaptalia |

| Species: | C. tomentosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Chaptalia tomentosa Vent. | |

| |

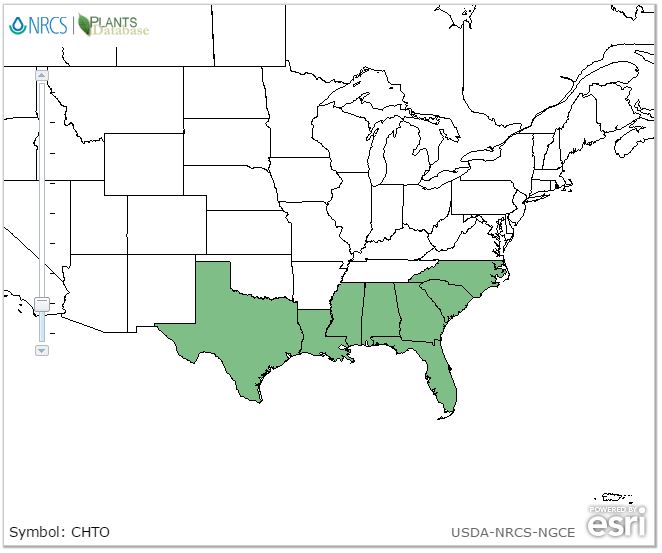

| Natural range of Chaptalia tomentosa from USDA NRCS [1]. | |

Common names: Woolly Sunbonnets; Pineland Daisy; Night-nodding Bog-dandelion; Sunbonnets

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

C. tomentosa is a perennial forb/herb that is a member of the Asteraceae family.[2] Leaf shape varies from elliptic to obovate with denticulate margins. The fruit type an achene (small, dry, and one-seeded). The flower is white with pinkish back petals.[3]

One study found the average maximum root depth to be 17 cm, and the average root porosity to be 14.3%.[4] Its life history is long-lived.[5]

Distribution

Chaptalia tomentosa is endemic to the longleaf pine range[6] of the Southeastern Coastal Plain, from east North Carolina to south Florida and west to east Texas.[7]

Ecology

Habitat

Chaptalia tomentosa is a facultative wetland species commonly found in seepage areas, edges of ditches, along streams, in low meadows, roadside wetlands, open bogs, and swampy woodlands. This species can occur in non-wetland areas such as sandhill seeps, savannas, and pine flatwoods.[7][2][8]

C. tomentosa grows in soil types ranging from sandy peat to moist or wet loamy sand.[8] One study found the species to increase in frequency when the overstory is thinned rather than clear cut.[9]C. tomentosa decreased in occurrence or was unaffected in response to soil disturbance by roller chopping in South Florida. It either resisted regrowth or remained unaffected in reestablished native habitat that was disturbed by roller chopping.[10] It increased in frequency in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests. It also showed positive regrowth in reestablished native flatwoods that were disturbed by clearcutting and chopping.[11]

Chaptalia tomentosa is frequent and abundant in the Upper and Lower Panhandle Savannas community type and is an indicator species for the Lower Panhandle Savannas community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[12]

Associated species include Pinus elliottii, Pinus palustris, Aristida sp., Serenoa repens, Hypericum fasciculatum, Sarracenia sp., Helenium vernale, Andropogon sp., Ascyrum tetrapetalum, Drosera brevifolia, Xyris sp., Taxodium sp., Sisyrinchium sp., Calopogon sp., Viola lanceolate, and Pinguicula sp.[8]

Phenology

C. tomentosa has been observed flowering from January to June with peak inflorescence in March.[13]

Fire ecology

The species could be hypothesized to be fire-tolerant since it is found in upper Florida panhandle savannas that are fire-dependent.[14] One study found C. tomentosa to significantly increase in frequency in response to a recent fire.[5] As number of growing seasons since past fire disturbance increases, one study found C. tomentosa to decrease in ground cover and frequency over the years.[15]

Herbivory and toxicology

It is considered to have poor forage value.[16]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Global status rank: G5 secure [17].

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 5 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ [[2]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 5, 2019

- ↑ Brewer, J. S., et al. (2011). "Carnivory in plants as a beneficial trait in wetlands." Aquatic Botany 94: 62-70.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hinman, S. E. and J. S. Brewer (2007). "Responses of Two Frequently-Burned Wet Pine Savannas to an Extended Period without Fire." The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 134(4): 512-526.

- ↑ Sorrie, B. A. and A. S. Weakley 2001. Coastal Plain valcular plant endemics: Phytogeographic patterns. Castanea 66: 50-82.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: March 2019. Collectors: William P. Adams, Luis Almodovar, Loran C. Anderson, K. Craddock Burks, George R. Cooley, R.K. Godfrey, C. Jackson, Percy Jones, Lisa Keppner, M. Knott, R. Komarek, R. Kral, John M. Kunzer, R. L. Lazor, Joseph Monachino, T. Myint, R. A. Norris, Elmer C. Prichard, Cecil R Slaughter, R. R. Smith, L. B. Trott, and Rodie White. States and Counties: Florida: Baker, Bay, Calhoun, Charlotte, Clay, Collier, Flagler, Franklin, Gulf, Jackson, Jefferson, Lee, Leon, Liberty, Martin, Okaloosa, Pasco, Santa Rosa, Volusia, Wakulla, Walton, and Washington. Georgia: Thomas.

- ↑ Brockway, D. G. and C. E. Lewis (2003). "Influence of deer, cattle grazing and timber harvest on plant species diversity in a longleaf pine bluestem ecosystem." Forest Ecology and Management 175: 49-69.

- ↑ Lewis, C.E. (1970). Responses to Chopping and Rock Phosphate on South Florida Ranges. Journal of Range Management 23(4):276-282.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 7 DEC 2016

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Lemon, P. C. (1949). "Successional responses of herbs in the longleaf-slash pine forest after fire." Ecology 30: 135-145.

- ↑ Hilman, J. B. (1964). "Plants of the Caloosa Experimental Range " U.S. Forest Service Research Paper SE-12

- ↑ [Encyclopedia of Life] Accessed 5 June 2016