Cornus florida

Common name: Flowering Dogwood

| Cornus florida | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Cornales |

| Family: | Cornaceae |

| Genus: | Cornus |

| Species: | C. florida |

| Binomial name | |

| Cornus florida L. | |

| |

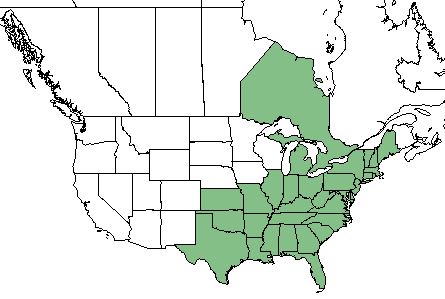

| Natural range of Cornus florida from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Cynoxylon floridum (Linnaeus) Rafinesque ex B.D. Jackson; Benthamidia florida (Linnaeus) Spach[1]

Varieties: none[1]

The genus name Cornus derives from the Latin word meaning a horn.[2]

Description

C. florida is a small, bushy, perennial shrub/tree of the Cornaceae family native to North America and Canada[3] that reaches heights of 40 feet with a diameter between 12 and 18 inches.[4] The bark is grayish brown, reddish brown, or black, rough, and broken into square blocks, and the leaves are deciduous, opposite, simple, nearly hairless and smooth to the touch on the upper surface with fine hair on bottom surface. The inflorescence is many flowers crowded into a head, subtended by 4 large and showy white-pink petal-like bracts. The fruit is an elliptical drupe, 1-2 seeded, bright red or yellowish at maturity, usually with several crowded together.[5]

Distribution

C. florida is native to the eastern continental United States west to Indiana, Missouri, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, as well as the Ontario region of Canada.[3] It is also native in montane northeast Mexico, including Veracruz and Nuevo Leon.[6]

Ecology

Habitat

C. florida can be found in a range of habitats from dry to moist forests to wetlands.[6] It does well in understories in the communities that it is found.[7]C. florida also proliferates in disturbed areas and rich woods.[8] Other habitats include bluffs and ravines, floodplains, gum swamps, and old-field communities. They are tolerant of dry periods that are seasonal, but are not tolerant of severe drought or saturated and heavy soils. With this, they are sensitive to quickly changing soil temperatures and prefer temperature-consistent woodland soils.[9] It is listed as a facultative upland species, where it mostly occurs in non-wetlands, but can still occur in wetlands.[3] C. florida is also associated with the pine-oak-hickory community type in the Gulf Coastal Plain.[10] The species grows best on rich and well-drained soils that are usually on middle and lower slopes.[4]

Cornus florida increased its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agricultural practices in South Carolina longleaf pinelands. It has shown regrowth in reestablished longleaf habitat that was disturbed by agricultural practices.[11] However, C. florida also showed resistance to regrowth in response agriculture-based soil disturbance in the same region, making it a remnant woodland indicator species.[12] It exhibits no response to soil disturbance by improvement logging in Mississippi.[13] Additionally, C. florida was found to be neutral in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[14]

Cornus florida is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[15]

Associated species include Carya sp., Quercus sp., Magnolia grandiflora, Vaccinium sp., Myrica cerifera, Symplocos tinctoria, Rubus sp., Smilax sp., Pinus sp., Rhus sp., Viola sp., Cnidoscolus sp., Aesculus sp., and Fagus sp.[8]

Phenology

C. florida has been observed flowering from February to April, October, and November. [16] The species has also been observed to fruit from May through November.[8]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates. [17] C. florida is a bird-dispersed species. [18] One study found that birds depended on perching availability for seed disturbance, where seeds of the Cornus genus were most commonly found under standard perches and snags and not the forest edge.[19] As well, trees were found to fruit heavily only every other year in one study, which affects the diet and presence of frugivores.[20]

Seed bank and germination

For best germination results, seeds should be stratified between 30 to 60 days at 41 degrees.[2]

Fire ecology

C. florida is not fire resistant, but has a medium fire tolerance.[3] The aboveground portion of the plant is easily damaged by fire since the bark is thin and allows fatal levels of heat to get to the cambrium quite quickly. Recovery post-fire is more rapid after surface fires rather than crown fires. The root crown commonly resporuts once the aboveground portion of the plant is damaged or even destroyed by fire disturbance.[9] Together, this decreases the browse palatability of the plant and affects the wildlife that use it as a food resource.[21] However, the tree tends to be more fruitful a couple years after fire disturbance.[22] Sapling density has been shown to decrease over time in response to fire introduction.[23] If burning cycles are implemented, C. florida was found to only benefit from at least a 9 year burn cycle.[24] The species proliferates with fire exclusion, with populations significantly increasing in response to a cease in fire regiment,[25] but populations of C. florida have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[26]

Pollination

Cornus florida has been observed to host ground-nesting bees such as Andrena forbesii (family Andrenidae), aphids from the family Aphididae such as Aphis sp. and Uroleucon sp., leafhoppers such as Erythroneura comes (family Cicadellidae), and assassin bugs from the Reduviidae family such as Phymata sp. and Zelus luridus.[27]

Herbivory and toxicology

C. florida consists of approximately 5-10% of the diet for large and small mammals, water birds, and terrestrial birds.[28] It is a food source during the winter and fall for the fox squirrel and grey squirrel, cedar waxwing, bobwhite quail, flicker, cardinal, robin, mockingbird, woodpecker, and wild turkey. The twigs and the leaves are eaten by white-tailed deer, and it is not an important plant for nesting.[4] As well, beavers and rabbits browse on the sprouts and leaves of the plant, and the tree provides shelter and various habitat for many wildlife species.[9] It is also a species of special value to native bees as well as supporting conservation biological control through attracting predatory or parasitoid insects that in turn prey upon pest insects. C. florida is a larval host for the spring azure (Celastrina ladon) as well.[2]

Diseases and parasites

C. florida has been impacted since the 1980s by widespread infection by the dogwood anthracnose fungus (Discula destructive).[6] Other pests and diseases include several wood boring insects and canker diseases that invade the main stem, and others that can attack the leaves and branches of the plant.[4] The dogwood borer larvae bore through openings in the bark to feed, where the cambrium can be destroyed and kill the tree. Twig borers can invade and kill young twigs by burrowing through the pith and leave ambrosia fungi for the larvae to feed on. As well, dogwood club-gall midge larvae can invade the twigs and cause them to swell at the base; only heavy infestation of this species can stunt the growth of the tree. Cankers can form on the tree at wound sites that allow infestation of fungi and harmful insects. Root rot can develop from root injury, over-fertilization, or a lack of soil drainage. Overall, this species is not very tolerant of stresses like drought, heat, salt, or pollution, and these stresses can make the plant more vulnerable to diseases and pests.[9]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

C. florida is listed as endangered by the Maine Department of Conservation Natural Areas Program, exploitably vulnerable by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Land and Forests, and threatened by the Vermont Department of Fish and Wildlife Nongame and Natural Heritage Program. [3] For timber stand improvement and tree harvest operations, 5 to 6 dogwoods should be left per acre for aesthetic purposes as well as a food source for wildlife.[4] For general management, C. florida is somewhat resistant to herbicides. Smaller resprouts occur when the stems are mechanically cut. When damaged by fire, the plant resprouts from the root crown once the aboveground vegetation is destroyed. For this species, extreme soil moisture and flooding is necessary. However, excess water leaves the plant susceptible to invasion by diseases and pests. Trees that are established in deep or partial shade only need irrigation in times of drought while trees in full sun need irrigation throughout their lifetime.[9] This species can be used in restoration efforts for urban forestry projects and even restoration of abandoned strip mines since C. florida is a soil improver due to the leaf litter decomposing quicker than most other species it associates with. There are many cultivars available for flowering dogwood, some examples including 'Bay Beauty', 'Cherokee Chief', 'Apple Blossom', 'Cherokee Brave', 'First Lady', 'Purple Glory', 'Cloud 9', 'Mystery', 'Welchii', and 'Sweetwater Red'.[9]

Cultural use

For humans the fruit is poisonous, but other portions of the plant have been used in the past. Historically, Native Americans used the root bark as a skin astringent, fever reducer, a pain reliever for various ailments, an antidiarrheal agent, and to even counteract many poisons as well as a general tonic. The bark itself was used for a throat aid, headaches and backaches, and as an infusion for some childhood diseases like measles. The flowers were utilized for fever reductions and colic pain relief. Finally, compound infusions of various parts of the plant were used as medicine for blood diseases and as blood purifiers.[9] In modern times, the wood of C. florida is harvested for charcoal, tool handles, hayforks, wheel cogs, and pulleys, and it is sometimes utilized for specialty items like golf club heads or knitting needles.[9]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 17, 2019

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=COFL2

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 USDA NRCS Plant Materials Program. (2006). Plant Fact Sheet: Flowering dogwood Cornus florida. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture.

- ↑ Gee, K. L., et al. (1994). White-tailed deer: their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ Concilio, A., et al. (2005). "Soil respiration response to prescribed burning and thinning in mixed-conifer and hardwood forests." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 35: 1581-1591.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Robert K. Godfrey, Gwynn W. Ramsey, Loran C. Anderson, William F. Sheridan, George R. Cooley, Joseph Monachino, J.P. Gillespie, Patricia Elliot, Gary R. Knight, K. Craddock Burks, Richard S. Mitchell, Lovett E. Willimas Jr., R.F. Christensen, C.C. Christensen, John W. Thieret, Windler, Keenan, Lombardo, Williams, A.J. Sharp, Evelyn Sharp, Frank Galyon, Clarke Hudson, R. Kral, R. L. Wyatt, Jerry C. Walters, George T. Jones, Roomie Wilson, Delzie Demaree, James, L. Luteyn, Jack P. Davis, Jewel Moore, W.R. Anderson, M.R. Crosby, Charles S. Wallis, Norlan C. Henderson, Charles Roach, Robert M. Downs, R.D. Whetstone, Mark A. Garland, Jolice Wiedenhoff, N. Summerlin, G. Gil, D.S. Kline, Harry E. Ahles, P. Crutchfield, Lloyd H. Shinners, R.E. Torrey, R.D. Houk, Gerald Poltorak, William D. Reese, C.L. Lundell, Amelia A. Lundell, W.F. Westerfeld, R.W. Booher, T. Sirko, H.A. Wahl, G.W. Parmelee, James R. Coleman, Andrew W. Westling, R.W. Nunan, William B. Masters, Kevin Oakes, Chris Cooksey, R. Komarek, W.M.D. Countryman. States and counties: Leon County Florida, Madison County Florida, Gadsden County Florida, Polk County Florida, Hernando County Florida, Wakulla County Florida, Liberty County Florida, Franklin County Florida, Jackson County Florida, Jefferson County Florida, Murray County Georgia, Iberia County Louisiana, Baltimore County Maryland, Sevier County Tennessee, Evangeline County Louisiana, Calcasieu County Louisiana, Natchitoches County Louisiana, Jefferson Davis County Mississippi, Lincoln County Louisiana, Forsyth County North Carolina, Bulloch County Georgia, Ashland County Ohio, Tangipahoa County Louisiana, Stone County Arkansas, Wake County North Carolina, Blount County Tennessee, Cobb County Georgia, Knox County Tennessee, Oconee County South Carolina, Muskogee County Oklahoma, Boone County Missouri, Morgan County West Virginia, Osage County Missouri, St. Mary County Louisiana, Marshall County Alabama, Stewart County Georgia, Grady County Georgia, Bastrop County Texas, Macon County North Carolina, Barbour County Alabama, Stone County Mississippi, Durham County North Carolina, Harrison County Mississippi, Wayne County Mississippi, Franklin County Massachusetts, Greene County Missouri, Ouachita County Louisiana, Union County Louisiana, Ingham County Michigan, Rapides County Louisiana, Montgomery County Virginia, Cherokee County Texas, Clearfield County Pennsylvania, Huntington County Indiana, Bradford County Pennsylvania, Lafayette County Louisiana, St. Landry County Louisiana, West Feliciana County Louisiana, De Kalb County Georgia, Transylvania County North Carolina, Dallas County Missouri, Thomas County Georgia, Cheshire County New Hampshire.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Wennerberg, S. (2006). Plant Guide: Flowering dogwood Cornus florida. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Baton Rouge, LA.

- ↑ Bostick, P. E. (1971). "Vascular Plants of Panola Mountian, Georgia " Castanea 46(3): 194-209.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ McComb, W.C. and R.E. Noble. (1982). Response of Understory Vegetation to Improvement Cutting and Physiographic Site in Two Mid-South Forest Stands. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society 47(1):60-77.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 18 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Myster, R. W. and S. T. A. Pickett (1993). "Effects of litter, distance, density and vegetation patch type on post dispersal tree seed predation in old fields." Oikos 66: 381-388.

- ↑ McClanahan, T. R. and R. W. Wolfe (1987). "Dispersal of ornithochorous seeds from forest edges in central Florida." Vegetatio 71: 107-112.

- ↑ Skeate, S. T. (1987). "Interactions between birds and fruits in a Northern Florida hammock community." Ecology 68(2): 297-309.

- ↑ Lay, D. W. (1967). "Browse palatability and the effects of prescribed burning in southern pine forests." Journal of Forestry 65: 826-828.

- ↑ (2000). The role of fire in nongame wildlife management and community restoration: Traditional uses and new directions, Nashville, TN, USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station.

- ↑ Albrecht, M. A. and B. C. McCarthy (2006). "Effects of prescribed fire and thinning on tree recruitment patterns in central hardwood forests." Forest Ecology and Management 226(1-3): 88-103.

- ↑ Bostick, P. E. (1971). "Vascular Plants of Panola Mountian, Georgia " Castanea 46(3): 194-209.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ Yarrow, G.K., and D.T. Yarrow. 1999. Managing wildlife. Sweet Water Press. Birmingham.