Brickellia eupatorioides

| Brickellia eupatorioides | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Anne Barkdoll and Rick Owens, Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Brickellia |

| Species: | B. eupatorioides |

| Binomial name | |

| Brickellia eupatorioides (L.) Shinners | |

| |

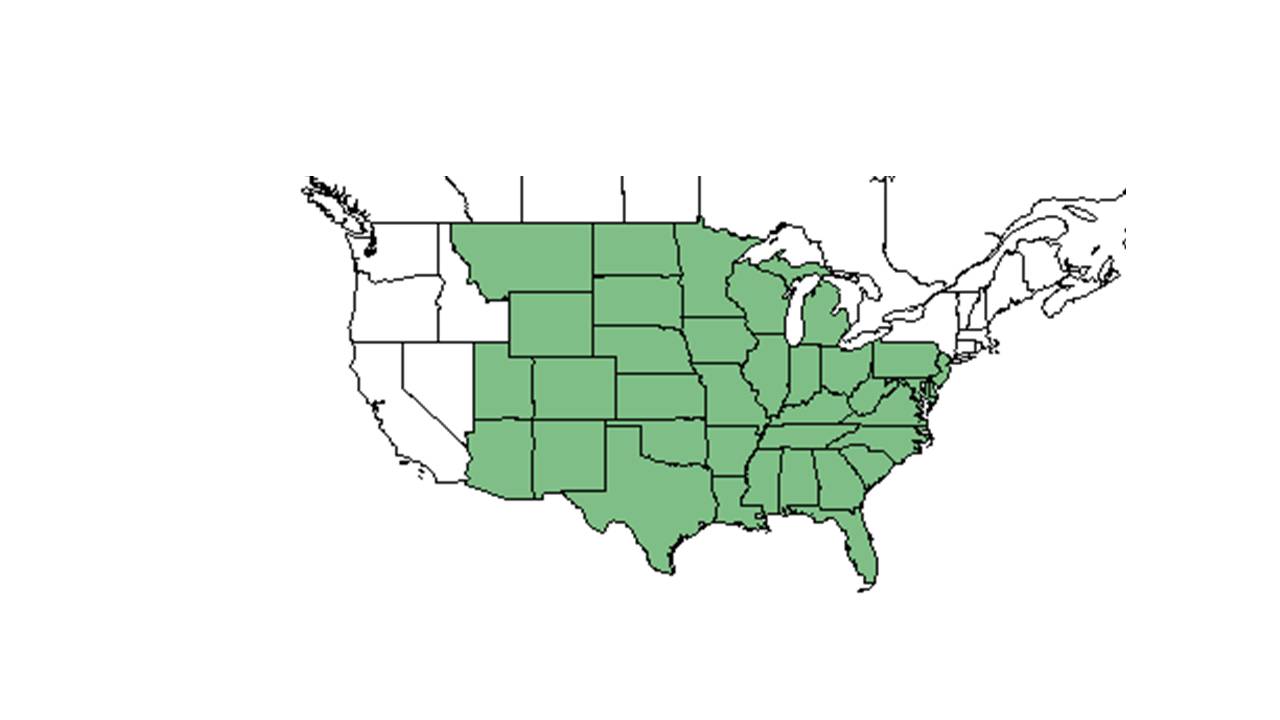

| Natural range of Brickellia eupatorioides from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: False Boneset, eastern Kuhnia

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Kuhnia eupatorioides (Linnaeus) Shinners var. eupatorioides; Kuhnia eupatorioides var. eupatorioides; Kuhnia eupatorioides var. pyramidalis Rafinesque[1]

Varieties: Brickellia eupatorioides (Linnaeus) Shinners var. corymbulosa (Torrey & Grey) Shinners; Brickellia eupatorioides (Linnaeus) Shinners var. eupatorioides; B. eupatorioides (Linnaeus) Shinners var. gracillama; B. eupatorioides (Linnaeus) Shinners var. texana[1]

Description

A description of Brickellia eupatorioides is provided in The Flora of North America.

Brickellia eupatorioides var. corymbulosa is a perennial that has been documented to be variable in habit, from erect and subvirgatte to decumbent, spreading or distinctly prostrate, arising from a slender deep-seated rootstock. [2][3]

Distribution

Ecology

Mycorrhizal relationships seemed to yield significantly higher phosphorous levels.[4]

Habitat

Brickellia eupatorioides is common in grassland communities[5], and is especially dominant in the tallgrass prairie.[6] In addition, this species occurs in pine-oak woodlands, open pinewoods, limestone glades, sandhills, longleaf pine-wiregrass communities, and hardwood hammocks. The plant has also been known to grow in disturbed areas including railways, roadside embankments, and open fields. B. eupatorioides appears in a range of light conditions, from semi-shade to full sun, and it prefers rocky or sandy soils. In Florida, it has been found in drying or moist loamy sand; in New Mexico, gravelly sand; in Texas, clay loam; and in Kansas, dry rocky soil.[7][2]

Associated species include Symphyotrichum concolor, Aster linariifolius, Aster phyllolepis, Campanula americana, Ageratina aromatica, Liatris gracilis, and others. [2]

Phenology

B. eupatorioides has been observed to flower July through November, and fruits in October.[2][8]

Seed dispersal

Achenes are long and cylindrical and have a tuft of white hair on top to aid in wind distribution. [9] This species is thought to be dispersed by wind. [10]

Seed bank and germination

It germinates well at 18-22 degrees Celsius.[4]

Fire ecology

Brickellia eupatorioides is fire tolerant[5] and populations are known to persist through repeated annual burns.[11] One study found B. eupatorioides to increase with frequency over time with summer burns.[12]

Pollination

Brickellia eupatorioides is pollinated by bumblebees, Halictid bees, and leaf cutting bees (Megachile spp.).[9] One study recorded Coelioxys octodentata pollinating B. eupatorioides.[13]

Herbivory and toxicology

The caterpillars of Schinia trifascia (three-lined flower moth), Schinia oleagina (Oleagina flower moth), and Schinia grandimedia (false boneset flower moth) feed destructively on the flowerheads and developing seeds.[9] Other insect feeders include Lygus lineolaris, Aphis coreopsidis, Dichagyris grotei, Melanoplus confusus (little pasture grasshopper), Melanoplus keeleri (Keeler's grasshopper), and Melanoplus discolor (contrasting spur-throated grasshopper). Entylia carinata (family Membracidae) has also be observed on this species.[14]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

It is listed as threatened by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and Energy.[3] Preference is full sun and dry conditions, although it can tolerate a little shade. Prefers poor soil that is made up of mostly clay, sand, or gravel. [9]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: L. C. Anderson, W. Baker, E. A. Bartholomew, S. F. Blake, J. R. Bozeman, J. R. Burkhalter, C. Cooksey, D. S. Correll, V. L. Cory, D. Demaree, J. Ewan, N Ewan, W. B. Fox, A. Gholson Jr., R. K. Godfrey, F. R. Hedges, N. C. Henderson, R. Komarek, J. Lazor, R. Lazor, R. Kral, S. McDaniel, J. B. Morrill, G. W. Parmelee, R. E. Perdue Jr., A. E. Radford, G. S. Ramseur, P. L. Redfearn Jr., J. A. Steyermark, B. C. Tharpe, and C. S. Wallis. States and Counties: Alabama: Jefferson and Talladega. Arkansas: Cleburne, Faulkner, and Logan. Colorado: Boulder and Lincoln. Florida: Calhoun, Decatur, Escambia, Gadsden, Jackson, Leon, Liberty, Madison, Suwannee, and Wakulla. Georgia: Decatur, Early, Grady, and Thomas. Iowa: Mills and Pottawatomie. Kansas: Hamilton and Johnson. Kentucky: Madison. Maryland: St. Marys. Michigan: Barry and Kent. Mississippi: Okibbeha. Missouri: Cass, Crawford, Greene, Jackson, Johnson, and Platte. New Mexico: Colfax. North Carolina: Alexander, Buncombe, and Richmond. Tennessee: Davidson. Texas: Crockett, Dallas, Gray, Kern, Milam, Ochiltree, Pecos, Tarrant, Williamson, and Wood. Virginia: Giles. West Virginia: Wirt.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 27 March 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kula, A. A. R., D. C. Hartnett, et al. (2005). "Effects of mycorrhizal symbiosis on tallgrass prairie plant-herbivore interactions." Ecology Letters 8: 61-69.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Bahm, M. A., T. G. Barnes, et al. (2011). "Herbicide and fire effects on smooth brome (Bromus inermis) and Kentucky bluegrass (Poa pratensis) in invaded prairie remnants." Invasive Plant Science and Management 4: 189-197.

- ↑ Towne 2002 cited by Kula et al 2005.More citation needed.

- ↑ Miller, J. H. and K. V. Miller (1999). Forest plants of the southeast, and their wildlife uses Champaign, IL, Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 27 MAR 2019

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 [[1]]Illinois Wildflowers. Accessed: April 4, 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Towne, E. G. and K. E. Kemp (2008). "Long-term response patterns of tallgrass prairie to frequent summer burning." Rangeland Ecology & Management 61: 509-520.

- ↑ Grundel, R., et al. (2011). "A survey of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of the Indiana Dunes and Northwest Indiana, USA." Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 84(2): 105-138.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]