Asclepias tuberosa

| Asclepias tuberosa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Gentianales |

| Family: | Asclepiadacea |

| Genus: | Asclepias |

| Species: | A. tuberosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Asclepias tuberosa (L) Brittonex Vail | |

| |

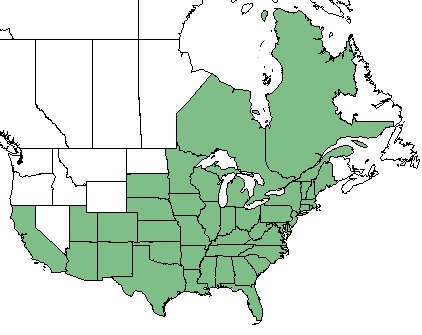

| Natural range of Asclepias tuberosa from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Names: midwestern butterfly-weed; sandhills butterfly-weed; common butterfly-weed; scrub butterflyweed; western butterflyweed;[1] butterfly milkweed; Rolfs' milkweed;[2] orange milkweed; pleurisy root; chigger flower[3]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Asclepias is named for Asklepio, the Greek god of medicine and healing. Humistrata is derived from the Latin word 'humis' meaning ground and 'sternere' to spread.[4]

Synonyms: Asclepias tuberosa ssp. terminalis Woodson; A. tuberosa Linnaeus ssp. interior Woodson; A. tuberosa Linnaeus var. interior (Woodson) Shinners; A. rolfsii Britton ex Vail; A. tuberosa ssp. rolfsii (Britton ex Vail) Woodosn; A. tuberosa ssp. tuberosa[1]

Varieties: Asclepias tuberosa Linnaeus var. cordata Beck; A. tuberosa Linnaeus var. rolfsii (Britton ex Vail) Shinners; A. tuberosa Linnaeus var. tuberosa; A. decumbens Linnaeus[1]

Description

In general, with the Asclepias genus, they are perennial herbs usually milky sap. The stems are erect, spreading or decumbent and usually are simple and often solitary. The leaves are opposite to subopposite, are sometimes whorled, and rarely alternate. The corolla lobes are reflexed and are rarely erect or spreading. The filaments are elaborate into five hood forming a corona around the gynosteguim. The corona horns are present in most species.[5]

Asclepias tuberosa, specifically, is a dioecious perennial forb/herb.[2] It is bushy and grows between 30 - 60 cm in height. The leaves are alternate, pointed, smooth on the edge, and 1.50 - 2.25 in (3.81 - 5.72 cm) long. Flat-topped clusters 2 - 5 in (5.1 - 12.7 cm) in diameter contain flowers[3] which range from a yellow to yellowish orange or a deep-orange to reddish.[1][3] with each cluster containing 88 - 94 flowers when grown in Michigan, but 79 - 87 when brought into and grown in a greenhouse.[6] Despite its common name and relatives, "milkweed", it has no milky sap.[3]

The root system of Asclepias tuberosa includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[7] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 404 mg/g (ranking 5 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 53.5% (ranking 10 out of 100 species studied).[7]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Asclepais tuberosa has stem tubers woth a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.915 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 404 mg g-1.[8]

Distribution

This species is found from Quebec and Maine, westward to Ontario and Minnesota, southwestward to South Dakota, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and California, and southward to central Texas, the Gulf Coast, and peninsular Florida.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

A. tuberosa occurs in roadbanks, dry forests, sandhills, woodland margins, roadsides, pastures, hardwood hammocks yellow sand sandhill savannas, and scrub.[1][9][10][11][12] It has been observed growing on dry coarse sandy soils, dry rocky soil, gravel, and peaty/silty soil.[13] In southern Iowa and northern Missouri grasslands, densities were 0.3 flowering ramets Dm-2.[14]

Associated species: Pinus palustris, Liatris sp., Panicum sp., Leptoloma cognatum, Imperata cylindrica, and Diospyros virginiana.[13]

Phenology

In the southeastern and mid-Atlantic United States, A. tuberosa has been observed to flower from April through November with peak inflorescence in May, and fruits from August through September.[15][1] As well, in North Port[9] and Walton County,[16] Florida, flowers have been observed blooming in April. Daylengths and cold storage lengths interact to influence the number of shoots, flowers, and length of time it takes for A. tuberosa to reach market stage.[6]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind. [17]

Seed bank and germination

Seed size is negatively correlated with A. tuberosa growth rates.[18]

Fire ecology

Populations of Asclepias tuberosa have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[19] In a Minnesota oak savanna, fire frequency of 2-19 burns from 1964-1984 showed no effect on the percent coverage of A. tuberosa.[20] Similarly, flowering of A. tuberosa in an Iowa prairie was uneffected by April burning.[21]

Pollination

This species is of special value to bumble bees, honey bees, and native bees, and can attract butterflies and hummingbirds as well.[3] In Arizona, the most important pollinators for A. tuberosa were Bombus sonorus, Apis mellifera, and small-sized bees. However, the presence of pollinators and their dominance varied between each year of the two year study. Other pollinators observed include Battus philenor (family Papilionidae), small-sized pollinators from the order Lepidoptera (i.e. Hesperiidae, Nymphalidae, Pieridae), medium-sized pollinators from the order Lepidoptera (i.e. Hesperiidae, Lycaenidae, Nymphalidae, Pieridae), medium sized pollinators from the order Hymenoptera (i.e. Anthophoridae, Megachilidae), and birds such as Archilochus alexandri (Trochilidae).[22]

Herbivory and toxicology

A. tuberosa has been observed to host brush-footed butterflies from the family Nymphalidae such as Phyciodes tharos[23] and Agraulis vanillae[16], bees from the family Apidae such as Bombus griseocollis, B. bimaculatus, Epeolus lectoides, Ceratina dupla and Ceratina strenua, sweat bees from the family Halictidae such as Augochlora pura, A. aurata, A. sumptuosa, Agapostemon splendens, Lasioglossum mitchelli, L. pectorale and L. subviridatum, and leafcutting bees from the family Megachilidae such as Ashmeadiella cactorum, Coelioxys octodentata, Dianthidium ulkei, D. heterulkei, D. pudicum, D. parvum, Heriades occidentalis, H. timberlakei, Coelioxys sayi, Osmia pumila, Megachile campanulae, M. texana M. mendica, and M. frugalis.[24][25] This species is also known to host gossamer-winged butterflies from the family Lycaenidae such as Lycaeides melissa samuelis[26], Strymon melinus and Satyrium titus.[27] This species composes 2-5% of the diet of some large mammals, including white-tailed deer, and terrestrial birds.[28][29] It is a host plant for flies in the Syrphidae and Tachinidae families[30], as well as Oncopeltus fasciatus (family Lygaeidae).[31]

Diseases and parasites

Known fungal diseases for A. tuberosa include: leafspot by Cercospora asclepiadorae, Cercospora clavata, and Phyllosticta tuberosa, leaf and stem blight by Diaporthe arctii, root rot by Phymatotrichum omnivorum, Pythiumsp., and Thielaviopsis basicola, and rust by Puccinia bartholomaei, Puccinia vexans, and Uromyces asclepiadis.[32]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

It is a priority species for habitat restoration efforts in the Rocky Mountains region, the Southern Plains region, the Great Lakes region, the Midwest, the Northeast, the Mid-Atlantic, the Southeast, and Florida.[32] A. tuberosa can be propagated via seeds or root cuttings. Root propagation can be performed in the fall by cutting the taproot into 2 in (5.1 cm) sections and planting each section vertically while keeping the soil moist.[3]

Cultural use

Historically, A. tuberosa was used by Native American tribes in the Missouri River region by the root eaten raw for pulmonary and bronchial trouble; it was also used for wounds by either chewing and placing on the wound or pulverizing when dry and blowing unto the wound. As well, it was utilized as a remedy for obstinate, old sores.[33] Though consuming larger quantities of any part of the plant can be toxic.[3], indigenous people also ingested the roots to treat colic, hysteria, hemorrhaging, gas, and weakness; a tea could also be made from the leaves to induce vomiting.[34]

It is also documented that native peoples would harvest and cook immature Asclepias tuberosa to eat as greens. The Dakota peoples would harvest immature seed pods and boil them to eat with meats. The seed pods can also be canned this way. It is also thought that indigenous Canadians would make a brown sugar by boiling dew off the milkweed plant. Additionally, the milk-like sap of the plant could be collected and used as a sort of chewing gum after sitting overnight.[35]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 13 February 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Plant database: Asclepias tuberosa. (13 February 2018) Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. URL: https://www.wildflower.org/plants/search.php?search_field=&newsearch=true

- ↑ [[1]]Florida Native Plant Society. Accessed: March 30, 2016

- ↑ Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 848-852. Print.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Albrecht ML, Lehmann JT (1991) Daylength, cold storage, and plant-production method influence growth and flowering of Asclepias tuberosa. HortScience 26(2):120-121.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz-Torbio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Observation by David Iannotti and identification by Edwin Bridges in North Port, Florida, April 16, 2017, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group April 16, 2017.

- ↑ Observation by Edwin Bridges in Lake Wales Ridge Wildlife and Environmental Area, Carter Creek Tract, Highlands County, FL, August 26,2017, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group August 26, 2017.

- ↑ Observation by Mark Reynolds in Charlotte County, FL, April 2, 2016, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group April 2, 2016.

- ↑ Observation by Kevin Songer in Lee County, FL, November 2, 2015, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group November 2,2015.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: March 2019. Collectors: Morris Adams, W. P. Adams, Nancy Allen, Loran C. Anderson, Raymond Athey, L. Baltzell, Adrian Bambini, Elizabeth Ann Bartholomew, C. R. Bell, James Bennett, Bunny Bergin, Kurt E. Blum, R. Buchanan, Kathy Craddock Burks, Michael Cartrett, Dorothy Cladin, Andre F. Clewell, Chris Cooksey, Cyrus Darling, Mr. H. A. Davis, Mrs. H. A. Davis, Jack P. Davis, M. Davis, Delzie Demaree, Robert Doren, Patricia Elliot, S. Ferguson, Tiffani Floyd, William T. Gillis, Robert K. Godfrey, S. J. Grant, H. E. Grelen, Norlan C. Henderson, Violet Hicks, D. C. Hunt, C. Jackson, S. B. Jones, Samuel B. Jones, Jr., Lisa Keppner, Gary R. Knight, R. Komarek, Robert Kral, Elmo Law, Robert L. Lazor, John F. Logue, Alpha Mae Looney, Sidney McDaniel, Richard S. Mitchell, K. Mori, Sydney Morthland, R. A. Norris, Bill Price, Elmer C. Prichard, Gwynn W. Ramsey, P. L. Redfearn, Jr., Don Reynolds, Cecil R. Slaughter, Dan Smalley, Michelle Marie Smith, R. R. Smith, Shelly Sparks, Steve Stafford, R. Stastny, Donald E. Stone, H. Larry E. Stripling, H. Sumanth, E. Laurence Thurston, Mike Turner, D. B. Ward, S. S. Ward, R. L. Wilbur, Lovett Williams, Jr., Mary Margaret Williams, Dale Wilson, Edgar T. Wherry, Virginia Whitman, and D. R. Windler. States and Counties: Florida: Calhoun, Charlotte, Collier, Dade, De Soto, Duval, Franklin, Gadsden, Hamilton, Hernando, Highlands, Hillsborough, Jackson, Jefferson, Lafayette, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Manatee, Marion, Okaloosa, Orange, Osceola, Pasco, Polk, Putnam, Seminole, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, and Washington. Georgia: Bulloch, Grady, Harris, McIntosh, and Thomas. Alabama: Geneva, Lowndes, Pickens, and Sumter. Kentucky: Christian and Livingston. Maryland: Baltimore. Tennessee: Grundy and Montgomery. Kansas: Cowley, Franklin, and Woodson. Missouri: Barry, Cass, Chariton, Dallas, Jackson, Ozark, Polk, and Webster. Arkansas: Garland, Saline, Washington, and Yell. Louisiana: Ouachita. West Virginia: Grant and Wirt. Texas: Callahan, Freestone, and Van Zandt. North Carolina: Alexander, Buncombe, Catawba, Granville, Jackson, Jones, Macon, Martin, and Surry. Mississippi: Carroll, Jackson, Kemper, and Yazoo. Indiana: Knox and Kosciusko. South Carolina: Allendale and Lancaster. New Jersey: Gloucester. Virginia: Giles. Pennsylvania: Delaware.

- ↑ Moranz RA, Debinski DM, McGranahan DA, Engle DM, Miller JR (2012) Untangling the effects of fire, grazing, and land-use legacies on grassland butterfly communities. Biodiversity and Conservation 21(11):2719-2746.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 22 MAR 2019

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Observation by Floyd Griffith in Walton County, FL, April 30, 2017, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group May 1, 2017.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Gleeson SK, Tilman D (1994) Plant allocation, growth rate and successional status. Functional Ecology 8:543-550.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Tester JR (1996) Effects of fire frequency on plant species in oak savanna in east-central Minnesota. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 123(4):304-308.

- ↑ Richards MS, Landers RQ (1973) Responses of species in Kalsow prairie, Iowa, to an April fire. Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science 80:159-161.

- ↑ Fishbein M, Venable DL (1996) Diversity and temporal change in the effective pollinators of Asclepias tuberosa. Ecology 77(4):1061-1073.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ Grundel, R., et al. (2011). "A survey of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of the Indiana Dunes and Northwest Indiana, USA." Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 84(2): 105-138.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [3]

- ↑ Grundel, R., et al. (2000). "Nectar plant selection by the Karner blue butterfly (Lycaeides melissa samuelis) at the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore." The American Midland Naturalist 144(1): 1-10.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [4]

- ↑ Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Atwood, E. L. (1941). "White-tailed deer foods of the United States." The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3): 314-332.

- ↑ Tooker, J. F., et al. (2006). "Floral host plants of Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) of central Illinois." Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99(1): 96-112.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [5]

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Borders, B. and E. Lee-Mader (2014). Milkweeds: A conservation practitioner's guide. Portland, The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation.

- ↑ Gilmore, M. R. (1919). Uses of plants by the indians of the Missouri River region. B. o. A. E. Smithsonian Institution. 33rd Annual Report.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.