Diospyros virginiana

Common Names: common persimmon[1], American persimmon; possumwood

| Diospyros virginiana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Ebenales |

| Family: | Ebenaceae |

| Genus: | Diospyros |

| Species: | D. virginiana |

| Binomial name | |

| Diospyros virginiana L. | |

| |

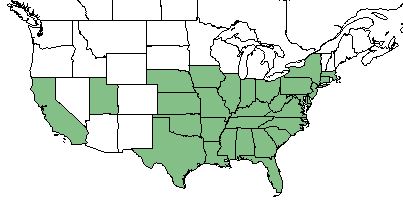

| Natural range of Diospyros virginiana from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: none[2]

Varieties: D. mosieri (Small); D. virginiana var. platycarpa Sargent; D. virginiana var. pubescens (Pursh) Nuttall; D. virginiana var. virginiana[2]

The genus name Diospyros derives from the Greek name meaning fruit of the god Zeus.[3]

Description

D. virginiana is a perennial tree of the Ebenaceae family native to North America.[1] Its common name, persimmon, is of Algonquian origin.[3] The tree can reach heights of 5 to 21 meters tall, with mature bark that is thick, blocky, and dark grey in color. Leaves simple, deciduous, alternately arranged, ovate to elliptic or oblong in shape, and entire with an acuminate apex as well as a rounded base. The underside of the leaves are usually lighter-colored, more often on younger leaves. The leaves can change color to a yellow or reddish-purple in the fall. Flowers staminate or pistillate borne on separate trees located on the shoots of the current year's growth. Pistillate flowers are short-stalked or sessile, bell-shaped, fragrant, corolla greenish-yellow to creamy, and 4 lobes. Staminate flowers are borne in clusters of 2 to 3 flowers, tubularly shaped, and greenish-yellow in color. Fruit is a greenish-yellow berry that contains a highly astringent pulp before ripe, and turns a yellow-orange color when ripe with 1 to 8 flat seeds inside.[4] East from the Mississippi River, D. virginiana has cuneate to rounded leaves at the base that are glabrous or glabrescent, while D. virginiana west of the Mississippi River have subcordate leaves that are persistently pubescent. These differences could be worthy of varietal recognition.[2]

Distribution

D. virginiana is found throughout the east coast and southeastern United States as well as California and Nevada. [1] While it is sparingly in other areas, its dominant distribution is in the east-central and southeastern United States.[4]

Ecology

Habitat

D. virginiana is easily adaptable to a wide range of soils and climates; it prefers moist and well-drained soils, but can also tolerate dry, hot, and poor soils. Habitats include from dry, sterile, and sandy woodlands to rocky hillsides and river bottoms. However, best growth is usually on clay and heavy loam soil on terraces of large streams and river bottoms. In the Mississippi Delta, it grows on shallow sloughs, wet flats, and swamp margins. It is shade tolerant, but grows best in full sun. In disturbed sites, it is usually an early pioneer species, and can commonly be found along fencerows and roadsides. It can also be found to grow in thickets in pastures and open fields.[4] All soils it can grow on include sandy and sandy loam, medium loam, clay loam and clay, acid-based, and calcareous.[3] D. virginiana is considered one of the most common mid-story vegetation in the upper panhandle savanna and clayhill longleaf woodlands in Florida. [5] As well, a variety of habitats have been visited for samples of D. virginiana including mixed woodlands, pine wiregrass community, lowland woodlands, old field, dry sandy soils, edge of branch swamp, and sandy ridge near swamp. [6] It also grows in pine-oak-hickory forests.[7] While it can be commonly found in upland habitats, it prefers lowland habitats.[8]

D. virginiana has shown positive regrowth in reestablished longleaf pinelands that were disturbed by agriculture-based soil disturbance in South Carolina's coastal plains, making it an indicator species for post-agricultural woodlands.[9] However, it was found to not respond to soil disturbance by agriculture in North Carolina or to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[10][11] D. virginiana was found to increase in frequency and density in response to soil disturbance by roller chopping in northwest Florida sandhills. It has also shown regrowth in reestablished native sandhill habitats that were disturbed by this practice.[12] D. virginiana was found to be neutral in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances but was an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[13]

Associated species: Quercus laevis, Quercus chapmannii, Quercus virginiana, Quercus geminata, Pinus palustris, Pinus elliottii var. densa, Aristida sp., Ximenia americana, Cyrilla parviflora, Nyssa sylvatica, Magnolia sp., and others.[6]

Diospyros virginiana is frequent and abundant in the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands and Upper Panhandle Savannas community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[14]

Phenology

General flowering time of D. virginiana is from May to June with fruiting occurring between September and December and persisting.[2] It has been observed flowering in April and May as well.[15] Preferred fruit-bearing age is between 25 to 50 years, even though fruit can start producing on 10 year old years.[4]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[16] These include being eaten by various birds as well as by various mammals.[17] One study found it to disperse great distances over a wide range of elevations.[17]

Seed bank and germination

D. virginiana can germinate easily from stratified seeds, even though scarification does not seem to improve germination rates. However, clipping the caps can bring more successful germination rates by encouraging radicle emergence instead. Seeds should be stratified in moist peat for 30 to 60 days at 36 to 41 degrees.[3]

Fire ecology

Populations of Diospyros virginiana have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[18][19] It is a common species in many fire-disturbed habitats.[20] D. virginiana has been shown to increase in frequency in response to fire disturbance, where one study found it to increase by 63%.[21] Another study found this species to have highest density in burned bluestem (Andropogon sp.) dominant habitats in northwest Florida.[22] Prescribed burns can be used to control the species, but fire exclusion can decrease its likelihood of surviving. As well, the roots and rootstocks of the plant can be killed with severe fires that char the soil, but less severe fires only top-kill the plant. When top-killed by fire or even cutting/pruning, vigorous sprouts produce from the root collar.[4] A study on fire exclusion found the number of trees to increase over time since fire disturbance, but for basal area to decrease.[23] It seems to benefit from 3 year and 6 year burn cycles.[24] One study by Schafer and Just conducted coppicing of multi-stemmed trees, including D. virginiana, to find how they are affected by disturbances like fire. They found this species to not be positively correlated with the pre-coppicing number of stems to number of resprouts, and speculated that factors like proximity of buds to the soil surface, bud activation, and pre-fire stem size could have affected the number of resprouts.[25]

Pollination

This plant is dioecious, meaning that male and female plants are separate individuals.[2] It is commonly pollinated by various native bees, and is of significant importance to these pollinators.[4][3]

Herbivory and toxicology

Flies of the families Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) have been collected from D. virginiana and is identified as a floral host.[26] More specifically this species has been observed to host assassin bugs such as Zelus luridus (family Reduviidae) and ground-nesting bees from the family Andrenidae such as Perdita bradleyi and P. townesi.[27]

This species consists of approximately 50-10% of the diet for large mammals, small mammals, and various terrestrial birds.[28] Bees use the nectar from the flowers for honey. White-tailed deer eat the twigs and leaves as well as the sprouts after fire or other disturbances. The fruit of the tree is eaten by squirrel, fox, skunk, deer, bear, coyote, racoon, opossum, quail, wild turkey, catbird, cedar waxwing and other various birds. Various natural defoliators of D. virginiana include the webworm (Seiarctica echo) and the hickory horned devil (Citheronia regalis).[4] The fruit has low pulp quality for birds.[29] It is also seldom eaten by gopher tortoises (Gopherus polyphemus).[30] This species is also an adult food source for the Luna moth (Actia luna).[3]

Diseases and parasites

D. virginiana can be susceptible to a wilt fungus (Cephalosporium diospyri) that kills many of these trees in the southeastern United States. Individuals can become infected through small branches being severed by a twig girdler (Oncideres cingulata), where these wounds leave the plant vulnerable to infection of the wilt fungus.[4] It is also a host plant of the false spider mite Brevipalpus phoenicis.[31]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

D. virginiana is listed as a species for special concern by the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, and it is listed as endangered by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Land and Forests.[1] It is an important species to conserve for it being one of the species that is fruit-bearing on sandhills that many species utilize.[32] This species, however, can be undesirable for growers of closely managed timber stands. For management, it can be mainly controlled by prescribed burns as well as various herbicides.[4] It is tolerant of the herbicides Dicamba, Hexazinone, and Triclopyr, and is susceptible to the herbicide Imazapyr.[33] A study found that managing areas for red cockaded woodpeckers brought an increase in frequency of D. virginiana.[34]

D. virginiana is a good species to utilize for erosion control due to its deep taproot. Various cultivars of this species are available, which were selected primarily for differentiating fruit taste, color, size, maturation time, and seedless cultivars.[4]

Cultural use

It is an edible fruit for humans as well, known for being sweet yet can be bitter if the fruit is not fully ripe.[2] The fruit can be used to make cookies, puddings, custard, cakes, and sherbet, and the seeds can be dried, roasted, and ground to make a substitute for coffee. The wood can be used for textile shuttles and heads for driver golf clubs due to it being smooth, hard, and even textured. The inner bark and unripe fruit can be used medicinally to treat fevers, diarrhea, and hemorrhage.[4] Native American tribes also used the species to make persimmon bread, and dried the fruit for storage. This fruit was the most prized by Native Americans in the southeastern United States.[3] The bark is an astringent, febrifuge, and anti-periodic, while the fruit is an astringent as well.[35] This species can also be diffused to make domestic liquors.[36]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 USDA Plant Database

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 3, 2019

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Nesom, G. and L. Moore (2006). Plant Guide: Common Persimmon Diospyros virginiana. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Baton Rouge, LA.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: R.K. Godfrey, Cecil Slaughter, Loran Anderson, T.Lott, B. Lund, Tom Barnes, Richard Mitchel, Gary Knight, Patricia Elliot, Bruce Hansen, Anne Perkins, Gwynn Ramsey, Karen MacClendon, M. Boothe, Leon Neel, Richard Gaskalla, R. Komarek, A. Johnson, M, Jenkins, Richard Carter. States and counties: Florida (Marion, Massau, Liberty, Franklin, Leon, Alachua, Wakulla, Highlands, Hernando, Jackson, Taylor, Collier, Lee, Sarasota, Gadsden, Suwannee, Calhoun, Washington, Holmes, Gulf) Georgia (Thomas, Grady, Lee)

- ↑ Bostick, P. E. (1971). "Vascular Plants of Panola Mountian, Georgia " Castanea 46(3): 194-209.

- ↑ Gilliam, F. S., et al. (2006). "Natural disturbances and the physiognomy of pine savannas: A phenomenological model." Applied Vegetation Science 9: 83-96.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 21 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Battaglia, L. L., et al. (2002). "Sixteen years of old-field succession and reestablishment of a bottomland hardwood forest in the lower Mississippi alluvial valley." Wetlands 22(1): 1-17.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Carter, R. E., et al. (2004). "Species composition of fire disturbed ecological land units in the Southern Loam Hills of south Alabama." Southeastern Naturalist 3: 297-308.

- ↑ Hartman, G. W. and B. Heumann (2003). Prescribed fire effects in the Ozarks of Missouri: the Chilton Creek Project 1996-2001. Second International Wildland Fire Ecology and Fire Management Congress and Fifth Symposium on Fire and Forest Meteorology, Orlando, FL, American Meteorological Society.

- ↑ Rodgers, H. L. and L. Provencher (1999). "Analysis of Longleaf Pine Sandhill Vegetation in Northwest Florida." Castanea 64(2): 138-162.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.

- ↑ Cain, M. D., et al. (1998). "Prescribed fire effects on structure in uneven-aged stands of loblolly and shortleaf pines." Wildlife Society Bulletin 26: 209-218.

- ↑ Schafer, J. L. and M. G. Just (2014). "Size dependency of post-disturbance recovery of multi-stemmed repsrouting trees." PLoS ONE 9(8): e105600.

- ↑ Tooker, J. F., et al. (2006). "Floral host plants of Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) of central Illinois." Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99(1): 96-112.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ Yarrow, G.K., and D.T. Yarrow. 1999. Managing wildlife. Sweet Water Press. Birmingham.

- ↑ White, D. W. and E. W. Stiles (1992). "Bird dispersal of fruits of species introduced into eastern North America." Canadian Journal of Botany 70(8): 1689-1696.

- ↑ Mushinsky, H. R., Terri A. Stilson and Earl D. McCoy (2003). "Diet and Dietary Preference of the Juvenile Gopher Tortoise " Herpetologists' League 59(4): 475-486.

- ↑ Childers, C. C., et al. (2003). "Host plants of Brevipalpus californicus, B. obovatus, and B. phoenicis (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) and their potential involvement in the spread of viral diseases vectored by these mites." Experimental & Applied Acarology 30: 29-105.

- ↑ Johnson, A. S. and J. L. Landers (1978). "Fruit production in slash pine plantations in Georgia." The Journal of Wildlife Management 42(3): 606-613.

- ↑ (2000). The role of fire in nongame wildlife management and community restoration: Traditional uses and new directions, Nashville, TN, USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station.

- ↑ Bowman, J. L., et al. (1999). Effects of red-cockaded woodpecker management on vegetative composition and structure and subsequent impacts on game species. Proceedings of the Fifty-third Annual Conference, Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies. A. G. Wong, P. Doerr, D. Woodward, P. Mazik and R. Lequire. Greensboro, NC, Southeastern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies: 220-234.

- ↑ Nickell, J. M. (1911). J.M.Nickell's botanical ready reference : especially designed for druggists and physicians : containing all of the botanical drugs known up to the present time, giving their medical properties, and all of their botanical, common, pharmacopoeal and German common (in German) names. Chicago, IL, Murray & Nickell MFG. Co.

- ↑ Porcher, F. P. (1869). Resources of the southern fields and forests, medical, economical, and agricultural. Richmond, VA, Order of the Surgeon-General.