Ambrosia artemisiifolia

| Ambrosia artemisiifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John R. Gwaltney Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Ambrosia |

| Species: | A. artemisiifolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. | |

| |

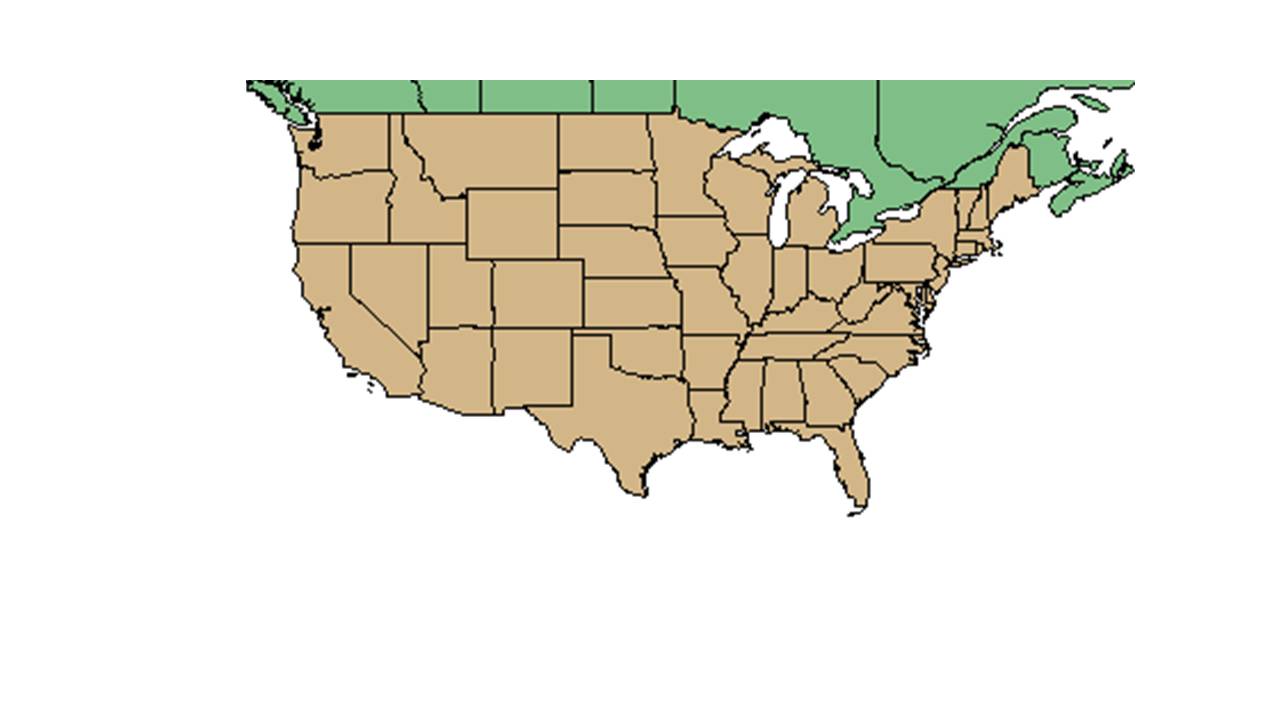

| Natural range of Ambrosia artemisiifolia from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Common ragweed

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: A. elatior Linnaeus; A. monophylla (Walter) Rydberg; A. glandulosa Scheele[1]

Description

Ambrosia artemisiifolia is an annual herb with pubescent, freely branched stems that can grow between 0.2 - 2 m tall. The leaves are oppositely arranged on most of the plant and alternately arranged on the upper portions; they are linear in shape, pubescent, 3 - 15 cm long and 0.5 - 3 mm wide with deep bipinnate dissection and acute sinuses and entire margins. The plant has a taproot, but primarily spreads through rhizomes.[2]

The flowers grow on racemes 3 - 20 cm long with a whorl of 1.5 - 3 mm bracts (modified small leaves) around the base (these whorls are known as involucres). The involucres of the pistillate (female) flowers are bundled in upper leaf axils, obovoid in shape, pubescent, 2.5 - 3.5 mm long and 1.5 - 2.5 mm in diameter with 5 - 6 projections toward the apex. The staminate (male) flower heads are 2 - 4 mm wide with around 5 lobes and situated on stalks 1 - 6 mm long. The nutlets produced by the plant are black or brown in color, obovoid in shape, pubescent at the apex, and 3 - 3.5 mm long.[2]

Distribution

A. artemisiifolia is distributed across the continental United States as both a native and introduced species, and is native to almost all provinces of Canada. It has also been introduced to Hawaii. [3]

Ecology

Habitat

It is common throughout Florida.[4] and throughout the entire United States.[5] It has been found in open pine woods, mixed hardwoods, wet hammocks, and along dried up shores of ponds. It does well in a number of disturbed areas including old fields, drainage ditches, pastures, roadsides, sandy vacant lots, railroad gravel, blackland prairie soil, camping areas, wet pastures, levees, drainage ditches, along edges of mixed forests, recently disturbed boggy areas, along canals, and agricultural fields. It thrives in dry sandy soils to wet, peaty soils in high intensity light in open areas.[6] A. artemisiifolia has been observed to be negatively impacted by soil disturbance in northeast Florida.[7].However, A. artemisiifolia has been found to be an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[8] It does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[9]

Ambrosia artemisiifolia is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[10]

Associated species include Agalinis divaricata, pine, hickory; Euphorbia, Andropogon, Bidens, Paspalum urvillei, Paspalum notatum, Eragrostis oxylepis, Eleusine indica, Digitaria sanguinalis, Cyperus surinamensis, Strophostyles helvola, Solanum americanum, Solanum sisymbriifolium, Daubentonia drummondii, Sesbania exaltata, cabbage palmetto, Emilia fosbergii, Paspalum setaceum, Heterotheca subaxillaris, Boerhavia diffusa, Bothriochloa ischaemum, Croton capitatus and various grasses.[6]

Phenology

Ambrosia artemisiifolia has been observed to flower between April and June to November and fruits from summer to late fall.[4][6][11]

Seed dispersal

Seeds are primarily distributed by animals,[12] but this species is also thought to be dispersed by wind.[13]

Seed bank and germination

It has a persistent seedbanks that can remain in the soil even after years of disturbance.[14] Seeds require an after-ripening period before germination occurs; germination occurs after near freezing temperatures.[15] While this is true, it is quite successful in seed germination due to being able to germinate in a large range of variable conditions, including temperatures between 5 to 40 degrees Celsius.[16] The initial dormancy of A. artemisiifolia can be attributed to presence of inhibitors like phenolic compounds and abscissic acid.[17]

Fire ecology

It can live where winter-burned annually and has been found in firelanes of annually-burned pinelands.[6][18] While fire increases the amount of bare ground, this in turn decreases competition and allows weedy forbs like A. artemisiifolia to greatly increase in numbers.[19] As well, A. artemisiifolia has been shown to proliferate with a high number of fire treatments.[20]

Herbivory and toxicology

A. artemisiifolia is one of the most important plant species for food and cover-producing for northern bobwhite quail.[21] The seeds are also consumed and utilized by various songbirds, the thirteen line ground squirrel, prairie deer mice, meadow vole, and prairie vole.[12] It is a common plant for white-tailed deer to browse in the Spring and Summer months.[21][22][23][24] Some species of caterpillars have been observed to eat the foliage, flowers and seeds. These species include geometer moths such as Synchlora aerata (family Geometridae), as well as owlet moths from the family Noctuidae such as Schinia rivulosa, Tarachidia erastrioides and Tarachidia candefacta.[12] Additionally, A. artemisiifolia has been observed to host tuft moths such as Diphthera festiva (family Nolidae), plant bugs such as Chlamydatus associatus (family Miridae), treehoppers such as Acutalis tartarea (family Membracidae), ladybugs such as Coccinella septempunctata (family Coccinellidae), cicadas such as Tibicen chloromera (family Cicadidae), leafhoppers from the family Cicadellidae such as Ceratagallia sp. and Empoasca sp., and planthoppers such as Pelitropis rotulata (family Tropiduchidae).[25]

Diseases and parasites

The pathogenic fungus Albugo tragopogi (white rust fungus) attacks ragweed and decreases pollen production. It is used as a control agent to limit the amount of ragweed allergens.[26]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Ragweed is a common allergen. While mowing A. artemisiifolia multiple times can reduce airborne pollen, this method of management does not affect the seed bank and would not stop the species from regerminating.[27] However, the pathogenic fungus Albugo tragopogi (white rust fungus) can be used as a control agent to limit the amount of ragweed pollen produced.[26] A. artemisiifolia is listed as a noxious weed within city limits in the state of Illinois, and listed as a "B" designated weed and quarantined in the state of Oregon.[3] Ragweed may also be responsible for dermatitis, as the leaves can be a skin irritant to some people.[28]

Cultural use

Historically, A. artemisiifolia was used by the Oto Native American tribe in the Missouri River region as a remedy for nausea. It was used on the surface of the abdomen, where the patient was scarified and then dressed with the bruised leaves.[29] It was also utilized by the Houma tribe in Louisiana for menstruation pain by making a tea out of the boiled roots.[30]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 1016-1018. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 USDA Plants Database URL: https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=ANGE

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Wunderlin, Richard P. and Bruce F. Hansen. Guide to the Vascular Plants of Florida. Second edition. 2003. University Press of Florida: Gainesville/Tallahassee/Tampa/Boca Raton/Pensacola/Orlando/Miami/Jacksonville/Ft. Myers. 296. Print.

- ↑ Hall, David W. Illustrated Plants of Florida and the Coastal Plain: based on the collections of Leland and Lucy Baltzell. 1993. A Maupin House Book. Gainesville. 74. Print.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Tom Barnes, R. Barbezat, Sarah Beem, S. Bennett, Kurt E. Blum, Michael B. Brooks, R. C. Darby, Frank DiCecco, William B. Fox, Mary A. Garland, Robert K. Godfrey, Bruce Hansen, G. G. Hedgcock, Norlan C. Henderson, Brenda Herrig, C. Jackson, T. Kanno, Robert Kral, Gary R. Knight, Elmo Law, Martha Lee, S. W. Leonard, S. J. Lombardo, C. L. Lundell, Travis MacClendon, Karen MacClendon, Sidney McDaniel, Richard S. Mitchell, J. B. Morrill, John B. Nelson, R. A. Norris, H. Okazaki, Dan Pittillo, A. E. Radford, Lloyd H. Shinners, Cecil R. Slaughter, Bill Stangler, William R. Stimson, Amanda R. Travis, Charles S. Wallis, Keenan Windler, and Wendy Zomlefer. States and Counties: Alabama: Baldwin. Colorado: Jefferson. Florida: Brevard, Columbia, Dade, Escambia, Franklin, Indian River, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Okaloosa, Pasco, Polk, Putnam, and Wakulla. Georgia: Colquitt, Decatur, Fulton, Grady, and Thomas. Illinois: Coles, Cook, and Lawrence. Iowa: Fremont. Louisiana: Ouachita. Kansas: Riley. Maryland: Baltimore. Mississippi: Harrison and Oktibbeha. Missouri: Cass, Greene, and Ray. North Carolina: Ashe, Chowan, Macon, Madison, and Wayne. Oklahoma: Ottawa. Pennsylvania: Huntingdon. South Carolina: Dorchester, Lexington, and Richland. Tennessee: Grundy and Polk. Texas: Dallas. Virginia: Giles, Montgomery, and Van Zandt. Other countries: Japan.

- ↑ Moore, W. H., et al. 1982. Vegetative response to clearcutting and chopping in a north Florida flatwoods forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 7 DEC 2016

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 [[1]]Illinois Wildflowers. Accessed: March 29, 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Rothrock, P. E., E. R. Squiers, et al. (1993). "Heterogeneity and Size of a Persistent Seedbank of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. and Setaria faberi Herrm." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 120(4): 417-422.

- ↑ Bazzaz, F. A. (1970). "Secondary Dormancy in the Seeds of the Common Ragweed Ambrosia artemisiifolia." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 97(5): 302-305.

- ↑ Sang, W., et al. (2011). "Germination and emergence of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. under changing environmental conditions in China." Plant Species Biology 26: 125-133.

- ↑ Dinelli, G., et al. (2013). "Germination ecology of Ambrosia artemisiifolia L. and Ambrosia trifida L. biotypes suspected of glyphosate resistance." Central European Journal of Biology 8: 286-296.

- ↑ Bakelaar, R. G. and E. P. Odum (1978). "Community and population level responses to fertilization in an old-field ecosystem." Ecology 59: 660-665.

- ↑ Curtis, J. T. and M. L. Partch (1948). "Effect of fire on the competition between blue grass and certain prairie plants." American Midland Naturalist 39: 437-443.

- ↑ Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Miller, J. H. and K. V. Miller (1999). Forest plants of the southeast, and their wildlife uses Champaign, IL, Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Atwood, E. L. (1941). "White-tailed deer foods of the United States." The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3): 314-332.

- ↑ Gee, K. L., et al. (1994). White-tailed deer: their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.

- ↑ Howard, W. E. and F. C. Evans (1961). "Seeds stored by prairie deer mice." Journal of Mammalogy 42(2): 260-263.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Hartmann, H. and A. K. Watson (1980). "Damage to Common Ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia) Caused by the White Rust Fungus (Albugo tragopogi)." Weed Science 28(6): 632-635.

- ↑ Simard, M.-J. and D. L. Benoit (2011). "Effect of repetitive mowing on common ragweed (Ambrosia artemisiifolia L.) pollen and seed production." Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine 18: 55-62.

- ↑ Hardin, J.W., Arena, J.M. 1969. Human Poisoning from Native and Cultivated Plants. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina.

- ↑ Gilmore, M. R. (1919). Uses of plants by the indians of the Missouri River region. B. o. A. E. Smithsonian Institution. 33rd Annual Report.

- ↑ Speck, F. G. (1941). "A list of plant curatives obtained from the Houma Indians of Louisiana." Primitive Man 14(4): 49-73.