Paspalum setaceum

Common names: thin paspalum[1], fringeleaf paspalum[2], hairy lens grass,[3] yellow sand paspalum[4]

| Paspalum setaceum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Shirley Denton hosted at Atlas of Florida Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae |

| Genus: | Paspalum |

| Species: | P. setaceum |

| Binomial name | |

| Paspalum setaceum Michx. | |

| |

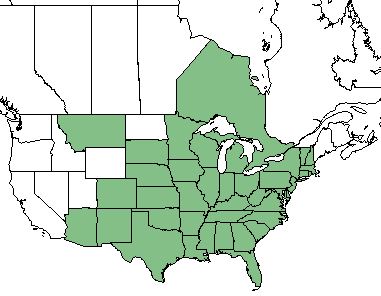

| Natural range of Paspalum setaceum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym: Paspalum ciliatifolium Michaux; P. ciliatifolium Michaux var. ciliatifolium; P. longepedunculatum LeConte; P. ciliatifolum Michaux var. muhlenbergii (Nash) Fernald; P. pubescens Muhlenberg ex Willdenow; P. setaceum var. muehlenbergii (orthographic variant); P. psammophilum Nash; P. rigidifolium Nash; P. ciliatifolium Michaux var. stramineum (Nash) Fernald; P. stramineum Nash; P. supineum Bosc ex Poiret; P. villosissimum Nash[4]

Varieties: Paspalum setaceum Michaux var. ciliatifolium (Michaux) Vasey; P. ciliatifolim Michaux; P. propinquum Nash; Paspalum setaceum Michaux var. longepedunculatum (LeConte) Alph; Paspalum setaceum Michaux var. muhlenbergii (Nash) Fernald; P. ciliatifolium Michaux var. muhlenbergii (Nash) Fernald; P. setaceum var. calvescens Fernald; Paspalum setaceum Michaux var. psammophilum (Nash) D.J. Banks; Paspalum setaceum Michaux var. rigidifolium (Nash) D.J. Banks; Paspalum setaceum Michaux var. setaceum; P. debile Michaux; P. setaceum Michaux var. stramineum (Nash) D.J. Banks; P. bushii Nash; Paspalum setaceum var. supinum (Bosc ex Poiret) Trinius; Paspalum setaceum Michaux var. villosissimum (Nash) D.J. Banks[4]

Description

Paspalum setaceum is a perennial graminoid of the Poaceeae family that is native to North America.[1] It has a tufted growth that originates from short rhizomes. The culms are 1-8 dm tall with glabrous nodes and internodes. The leaves are basal and cauline. The blades are 4 dm long and 12 mm wide, glabrous or pubescent, with scaberulous and ciliate margins. The sheaths are glabrous or pubescent, with scarious and ciliate margins. Ligules are membranous, ciliate apically, and 2-6 mm long. There are 1-2 racemes which are terminal and axillary, 4-14 cm long, with scaberulous pedicels that are 0.5-1.2 mm long.[4]

Paspalum setaceum does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its rhizomes.[5] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 39.7 mg/g (ranking 81 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 55.6% (ranking 33out of 100 species studied).[5]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Paspalum setaceum has rhizomes with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.356 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 39.7 mg g-1.[6]

Distribution

P. setaceum is found throughout the majority of the continental United States, excepting western states North Dakota, Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, Idaho, Washington, Oregon, and California. It is also found in Ontario, Canada.[1]

Paspalum setaceum var. psammophilum is endemic to an area from southeastern Massachusetts to southern New Jersey and adjacent Delmarva Peninsula.[7]

Ecology

Habitat

Habitats include sandhills, savannas, and other dry soils. Other varieties can be found in grasslands, pine flatwoods, pine savannas, old fields, and other fields.[4] Specimens have been collected from habitats such as dry sand of grass clearing, a wooded ridge with sandy loam, open wet pine flatwoods and mixed hardwood swamps, floodplain forest, shade near lakes, coastal hammock, pine flatwoods, fire run in a flatwood, botanical gardens, sandhill, and waste ground.[8]

P. setaceum increased its occurrence in response to roller chopping in south Florida.[9] It increased its frequency in response to clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods.[10] It has also increased its occurrence in response to agriculture in South Carolina longleaf pine.[11] Additionally, this species has increased its foliar cover in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and roller chopping in north Florida.[12] It has shown regrowth in reestablished native habitat that was disturbed by these practices, making it a post-agricultural woodland indicator species.[9][10][11][12]

This species has had mixed responses to chopping, disking, fertilizing, and bedding in south Florida prairie. It either increased its biomass or was unaffected by these practices.[13]

Paspalum setaceum is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills, North Florida Longleaf Woodlands, North Florida Subxeric Sandhills, and Central Florida Flatwoods/Prairies community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[14]

Phenology

P. setaceum has been observed flowering in June.[15]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[16] It has been found that gopher tortoises can disperse the seeds of the grass through their scat. The germination success of these partially digested seeds is much lower than those that are not.[17]

Fire ecology

Populations of Paspalum setaceum have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[18][19][20]

Herbivory and toxicology

P. setaceum provides forage for livestock and deer in Texas.[1] This species has been known to hold up well to and increase in response to heavy grazing by cattle.[21] Birds have been observed to eat the seeds.[1]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 USDA Plant Database

- ↑ Gee, K. L., et al. (1994). White-tailed deer: their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.

- ↑ Goldblum, D., et al. (2013). "The impact of seed mix weight on diversity and species composition in a tallgrass prairie restoration planting, Nachusa grasslands, Illinois, USA." Ecological Restoration 31(2): 154-167.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ Sorrie, B. A. and A. S. Weakley 2001. Coastal Plain valcular plant endemics: Phytogeographic patterns. Castanea 66: 50-82.

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, Roy Komarek, DJ Banks, RA Norris, Andre F. Clewell, Kevin Oakes, Chris Cooksey, M. Davis, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, Cecil Slaughter, M. Darst, A. Stiles, H. Light, J. Good, L. Peed, K. Smith, R. A. Pursell, A.H. Curtiss, Sidney McDaniel, Robert J Lemaire, Gwynn W. Ramsey, R. E. Perdue Jr., H. Kurz, R. F. Thorne, R. A. Davidson, R. S. Mitchell, W. Reese, P. Redfearn, W.C. Brumbach, Angus Gholson, Daniel B. Ward, S.T. Cooper, James B McFarlin, Silvus, Grady W. Reinert, A.A. Eaton, Richard Carter, Paul O. Schallert, Travis MacClendon, Karen MacClendon. States and counties: Florida ( Wakulla, Liberty, Franklin, Santa Rosa, Jefferson, Jackson, Leon, Suwannee, Putnam, Flagler, Osceola, Dixie, Levy, Seminole, Volusia, Walton, Lee, Martin, Gadsden, Holmes, Pinellas, Clay, Polk, Marion, Monroe, Gulf, bay, Sarasota, Highland, Nassau, Dade, Hernando, Escambia, Gilchrist) Georgia (Charlton, Gadsden, Thomas, Grady, Clinch)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lewis, C.E. (1970). Responses to Chopping and Rock Phosphate on South Florida Ranges. Journal of Range Management 23(4):276-282.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.

- ↑ Moore, W.H. and B.F. Swindel. (1981). Effects of Site Preparation on Dry Prairie Vegetation in South Florida. Southern Journal of Applied Forestry 27(2)89-92.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 24 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Carlson, J. E., et al. (2003). "Seed dispersal by Gopherus polyphemus at Archbold Biological Station, Florida." Florida Scientist 66: 147-154.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Byrd, Nathan A. (1980). "Forestland Grazing: A Guide For Service Foresters In The South." U.S. Department of Agriculture.