Difference between revisions of "Smilax auriculata"

KatieMccoy (talk | contribs) |

KatieMccoy (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | + | In the Coastal Plain in Florida and Georgia, ''S. auriculata'' can be found bordering mesic woodlands, longleaf pine turkey oak sand ridges (FSU Herbarium), palmetto flatwoods (FSU Herbarium; Olano et al. 2006), oak-saw palmetto scrubs (Foster and Schmalzer 2003), sandhill communities (FSU Herbarium; Reinhart et al. 2004), xeric longleaf pine woodlands (Peet and Allard 1993), and unburned scrubby flatwoods (Menges and Kohfeldt 1995). It can also be found along railroads, powerline corridors, and disturbed longleaf pine restoration sites (FSU Herbarium). Soil types include loamy sand (FSU herbarium; Foster and Schmalzer 2003) and sandy, siliceous, hyperthermic Ultic haplaquod of the Pomona series (Moore et al. 1982). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | In habitats that include ''Pinus palustris, Quercus laevis, Q. incana, Sporobolus junceus'' and ''Licania michauxii'', ''S. auriculata'' accounts for most of the groundcover density (Rodgers and Provencher 1999). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

“is a woody vine with large specializes storage organs enabling rapid postfire recovery.” – Olano et al 2006. | “is a woody vine with large specializes storage organs enabling rapid postfire recovery.” – Olano et al 2006. | ||

Revision as of 13:24, 7 October 2015

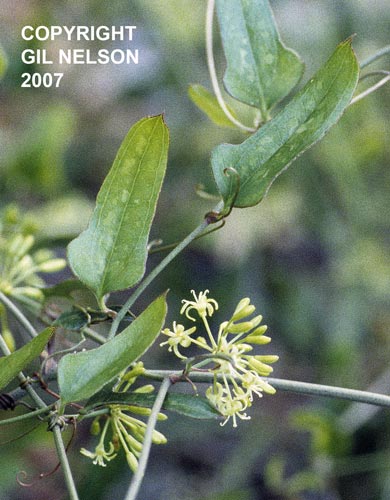

| Smilax auriculata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta – Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida – Monocotyledons |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Smilacaceae |

| Genus: | Smilax |

| Species: | S. auriculata |

| Binomial name | |

| Smilax auriculata Walter | |

| |

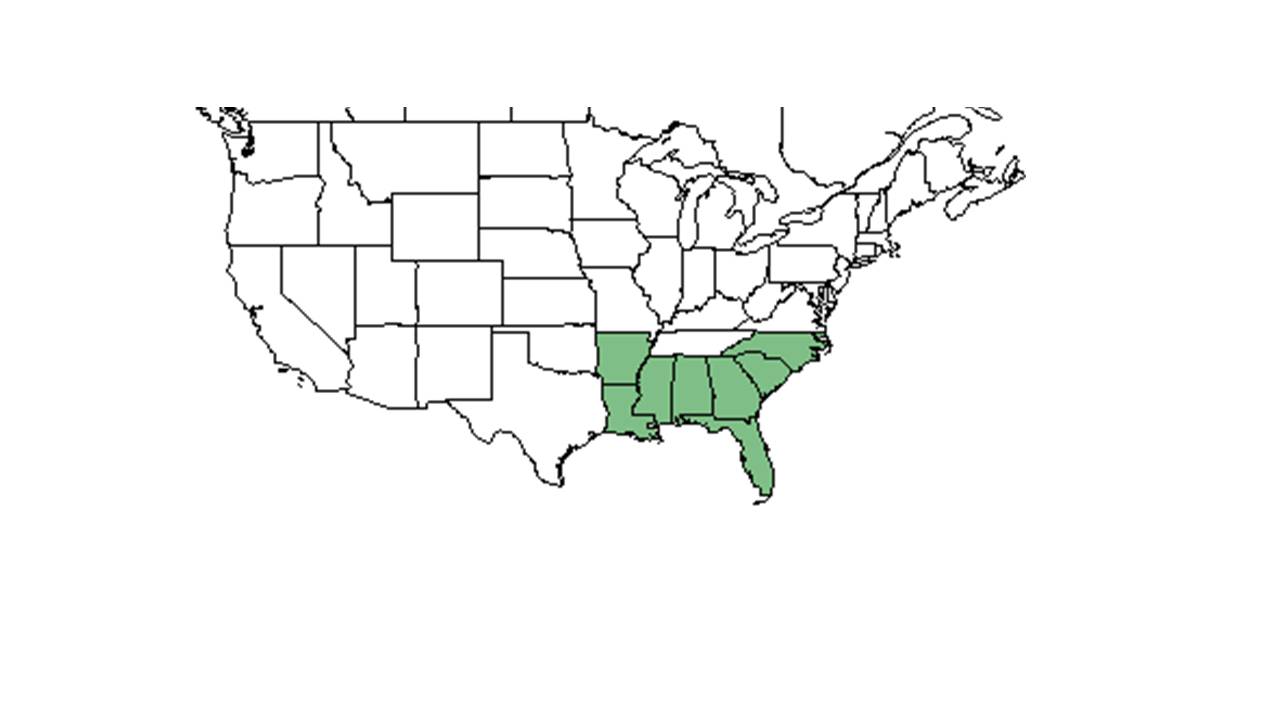

| Natural range of Smilax auriculata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: earleaf greenbrier

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Description

A description of Smilax auriculata is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain in Florida and Georgia, S. auriculata can be found bordering mesic woodlands, longleaf pine turkey oak sand ridges (FSU Herbarium), palmetto flatwoods (FSU Herbarium; Olano et al. 2006), oak-saw palmetto scrubs (Foster and Schmalzer 2003), sandhill communities (FSU Herbarium; Reinhart et al. 2004), xeric longleaf pine woodlands (Peet and Allard 1993), and unburned scrubby flatwoods (Menges and Kohfeldt 1995). It can also be found along railroads, powerline corridors, and disturbed longleaf pine restoration sites (FSU Herbarium). Soil types include loamy sand (FSU herbarium; Foster and Schmalzer 2003) and sandy, siliceous, hyperthermic Ultic haplaquod of the Pomona series (Moore et al. 1982).

In habitats that include Pinus palustris, Quercus laevis, Q. incana, Sporobolus junceus and Licania michauxii, S. auriculata accounts for most of the groundcover density (Rodgers and Provencher 1999).

Phenology

“is a woody vine with large specializes storage organs enabling rapid postfire recovery.” – Olano et al 2006.

Seed dispersal

Seed bank and germination

It can reproduce by resprouting, clonal spreading, and seeding (Menges and Kohfeldt 1995).

Fire ecology

It increases in abundance after fire (Menges and Kohfeldt 1995). Its rapid recovery post-fire can be attributed to large specialized storage organs (Olano et al 2006). However, Greenberg found out that S. auriculata decreased to almost nonexistent following a May fire (2003). This suggests that season of burning is important for this species.

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Smilax auriculata at Archbold Biological Station (Deyrup 2015):

Apidae: Apis mellifera

Halictidae: Augochlora pura

Megachilidae: Coelioxys dolichos, Megachile mendica, M. xylocopoides

Use by animals

S. auriculata was found in 5.5% of the Gopherus polyphemus scat observed by Carlson and her team (2003). Thus, the gopher tortoise can serve as an agent of seed dispersal. Deyrup (2002) observed these bees, Augochlora pura, Coelioxys dolichos, Megachile mendica, M. xylocopoides, Apis mellifera, Xylocopa micans, X. virginica krombeini, on S. auriculata.

Diseases and parasites

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Carlson, J. E., E. S. Menges, et al. (2003). "Seed dispersal by Gopherus polyphemus at Archbold Biological Station, Florida." Florida Scientist 66: 147-154.

Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

Deyrup, M. and L. Deyrup (2012). "The diversity of insects visiting flowers of saw palmetto (Arecaceae)." Florida Entomologist 95(3): 711-730.

Greenberg, C. H. (2003). "Vegetation recovery and stand structure following a prescribed stand-replacement burn in sand pine scrub." Natural Areas Journal 23: 141-151.

Menges, E. and N. Kohfeldt (1995). "Life History Strategies of Florida Scrub Plants in Relation to Fire." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 122(4): 282-297

Menges, E. S. and N. M. Kohfeldt (1992). Life history strategies of scrub plants in relation to fire [abstract]. History and Ecology of the Florida scrub, Lake Placid, FL, Archbold Biological Station.

Moore, W. H., B. F. Swindel, et al. (1982). "Vegetative response to prescribed fire in a north Florida flatwoods forest." Journal of Range Management 35: 386-389.

Olano, J. M., E. S. Menges, et al. (2006). "Carbohydrate storage in five resprouting Florida scrub plants across a fire chronosequence." New Phytologist 170: 99-105.

Provencher, L. M., B. J. Herring, et al. (2001). "Effects of hardwood reduction techniques on longleaf pine sandhill vegetation in northwest Florida." Restoration Ecology 9: 13-27.

Reinhart, K. O. and E. S. Menges (2004). "Effects of re-introducing fire to a central Florida sandhill community." Applied Vegetation Science 7: 141-150.

Schmalzer, P. A., S. R. Turek, et al. (2002). "Reestablishing Florida scrub in a former agricultural site: survival and growth of planted species and changes in community composition." Castanea 67: 146-160.