Difference between revisions of "Gaylussacia dumosa"

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | ''Gaylussacia dumosa'' commonly grows in pine savannas and other habitats that are frequently burned.<ref name= "herbarium"/> It increases in frequency in response to fire, but crown height and width over time since fire does not change much.<ref>Abrahamson, W. (1984). "Post-Fire Recovery of Florida Lake Wales Ridge Vegetation." American Journal of Botany 71(1): 9-21.</ref> One study found the amount of cover to dramatically increase in response to fire, but as time increased since fire disturbance, the percent cover of ''G. dumosa'' to decrease.<ref>Abrahamson, W. G. (1984). "Species Responses to Fire on the Florida Lake Wales Ridge." American Journal of Botany 71(1): 35-43.</ref> | + | ''Gaylussacia dumosa'' commonly grows in pine savannas and other habitats that are frequently burned.<ref name= "herbarium"/> It increases in frequency in response to fire, but crown height and width over time since fire does not change much.<ref>Abrahamson, W. (1984). "Post-Fire Recovery of Florida Lake Wales Ridge Vegetation." American Journal of Botany 71(1): 9-21.</ref> One study found the amount of cover to dramatically increase in response to fire, but as time increased since fire disturbance, the percent cover of ''G. dumosa'' to decrease.<ref>Abrahamson, W. G. (1984). "Species Responses to Fire on the Florida Lake Wales Ridge." American Journal of Botany 71(1): 35-43.</ref> It is easily ignitable due to average litter depth and bulk density which adds to the fine fuels from the plant that are able to ignite.<ref>Behm, A. L., et al. (2004). "Flammability of native understory species in pine flatwood and hardwood hammock ecosystems and implications for the wildland-urban interface." International Journal of Wildland Fire 13: 355-365.</ref> |

===Pollination=== | ===Pollination=== | ||

Revision as of 15:57, 15 May 2019

| Gaylussacia dumosa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Ericaceae |

| Genus: | Gaylussacia |

| Species: | G. dumosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Gaylussacia dumosa (Andrews) Torr. & A. Gray | |

| |

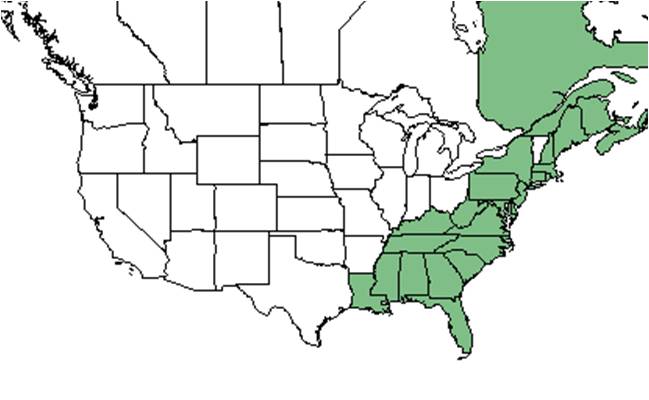

| Natural range of Gaylussacia dumosa from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Dwarf huckleberry; Southern dwarf huckleberry

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Gaylussacia dumosa (Andrews) Torrey var. dumosa; Lasiococcus dumosus (Andrews) Small

Description

A description of Gaylussacia dumosa is provided in The Flora of North America. Size class of this plant is between 1 and 3 feet.[1]

Distribution

Its main distribution is throughout the southeastern coastal plain, from New Jersey to Florida and west to eastern Louisiana, and less common more inland.[2] It is also native to the Canadian provinces of Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland & Labrador; it is also found in St. Pierre Miquelon located near Newfoundland & Labrador province.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

Gaylussacia dumosa is commonly found in mesic to xeric, acidic woodlands and forests.[2] This species has also been observed in a variety of habitats including pine and saw palmetto flats and other flatwoods, pine plantations, low pine savannas, scrub, sand ridges, bluffs, edge of a pitcher plant bog, and sandhills. Soils include drying and moist sand, acid sandy peat, sandy loam, and sandy to mucky soils.[4] It is restricted to native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of South Georgia. [5] G. dumosa responds negatively to soil disturbance in longleaf pine communities in South Carolina.[6] However, it has been observed in some slightly disturbed areas including along the edge of open powerline corridors, a disturbed wiregrass area cleared by rootrake, and sandy roadsides.[4] In other areas, it can also be found in low pinelands as well as bogs and pond margins.[1]

Associated species include Andropogon sp., Aristida stricta, Aristida sp., Sorghastrum sp., Pinus palustris, Pinus elliottii, Serenoa repens, Vaccinium darrowii, Vaccinium myrsinites, Vaccinium sp., Quercus laevis, Quercus minima, Quercus pumila, Diospyros virginiana, Actinospermum angustifolium, Leptoloma cognatum, Gaylussacia sp., Kalmia hirsuta, and others.[4]

Phenology

Generally, G. dumosa flowers from March to June and fruits from June until October.[2] It has been observed to flower March to May and in October with peak inflorescence in April, and fruit from April until July.[7][4]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates. [8] In particular, it has found to be dispersed by gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus).[9]

Fire ecology

Gaylussacia dumosa commonly grows in pine savannas and other habitats that are frequently burned.[4] It increases in frequency in response to fire, but crown height and width over time since fire does not change much.[10] One study found the amount of cover to dramatically increase in response to fire, but as time increased since fire disturbance, the percent cover of G. dumosa to decrease.[11] It is easily ignitable due to average litter depth and bulk density which adds to the fine fuels from the plant that are able to ignite.[12]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Gaylussacia dumosa at Archbold Biological Station: [13]

Apidae: Apis mellifera, Bombus impatiens

Halictidae: Augochlorella aurata, A. gratiosa

Megachilidae: Megachile brevis pseudobrevis, M. integrella

Use by animals

It consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for large mammals, 5-10% of the diet for small mammals, and 5-10% of the diet for various terrestrial birds.[14][15]

Conservation and management

Gaylussacia dumosa is listed as threatened by the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, the New Hampshire Division of Forests and Lands, and the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. It is listed as endangered by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, and is listed as a species of special concern by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management.[3]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 15, 2019

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 15 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: May 2019. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Edwin L. Bridges, D. Burch, S. Clawson, Andre F. Clewell, George R. Cooley, M. Davis, Patricia Elliot, Bob Fewster, J. P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, H. E. Grelen, D. Kennemore, R. Kral, Karen MacClendon, Sidney McDaniel, Marc C. Minno, R. S. Mitchell, John B. Nelson, Steve L. Orzell, Elmer C. Prichard, Gwynn W. Ramsey, Helen Roth, Annie Scmidt, Robert W. Simons, Cecil R. Slaughter, L. B. Trott, D. B. Ward, Kenneth A. Wilson, and Carroll E. Wood, Jr. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Calhoun, Clay, Columbia, Escambia, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Hamilton, Hernando, Highlands, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Manatee, Nassau, Okaloosa, Polk, St Johns, Suwannee, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Thomas.

- ↑ Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 9 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kay Kirkman, Jones Ecological Research Center, unpublished data, 2015.

- ↑ Carlson, J. E., E. S. Menges, and P. L. Marks. 2003. Seed dispersal by Gopherus polyphemus at Archbold Biological Station, Florida. Florida Scientist, v. 66, no. 2, p. 147-154.

- ↑ Abrahamson, W. (1984). "Post-Fire Recovery of Florida Lake Wales Ridge Vegetation." American Journal of Botany 71(1): 9-21.

- ↑ Abrahamson, W. G. (1984). "Species Responses to Fire on the Florida Lake Wales Ridge." American Journal of Botany 71(1): 35-43.

- ↑ Behm, A. L., et al. (2004). "Flammability of native understory species in pine flatwood and hardwood hammock ecosystems and implications for the wildland-urban interface." International Journal of Wildland Fire 13: 355-365.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Yarrow, G.K., and D.T. Yarrow. 1999. Managing wildlife. Sweet Water Press. Birmingham.