Gaylussacia dumosa

| Gaylussacia dumosa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Ericaceae |

| Genus: | Gaylussacia |

| Species: | G. dumosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Gaylussacia dumosa (Andrews) Torr. & A. Gray | |

| |

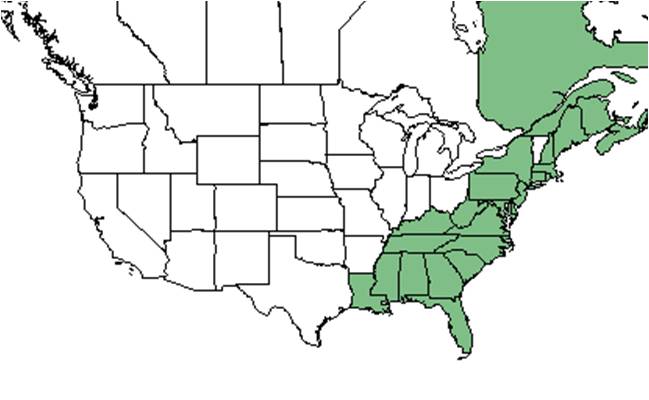

| Natural range of Gaylussacia dumosa from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: dwarf huckleberry; southern dwarf huckleberry

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Gaylussacia dumosa (Andrews) Torrey var. dumosa; Lasiococcus dumosus (Andrews) Small[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

A description of Gaylussacia dumosa is provided in The Flora of North America. Size class of this plant is between 1 and 3 feet.[2] It is usually short-statured with leaves that are leathery and relatively small.[3]

Distribution

Its main distribution is throughout the southeastern coastal plain, from New Jersey to Florida and west to eastern Louisiana, and less common more inland.[1] It is also native to the Canadian provinces of Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland & Labrador; it is also found in St. Pierre Miquelon located near Newfoundland & Labrador province.[4]

Due to 90% of the documented individuals occurring in disjunct populations throughout the coastal plain and Appalachian mountains, G. dumosa var. bigeloviana is considered endemic to this region.[5]

Ecology

Habitat

Gaylussacia dumosa is commonly found in mesic to xeric, acidic woodlands and forests.[1] This species has also been observed in a variety of habitats including pine and saw palmetto flats and other flatwoods, pine plantations, low pine savannas, scrub, sand ridges, bluffs, edge of a pitcher plant bog, and sandhills. Soils include drying and moist sand, acid sandy peat, sandy loam, and sandy to mucky soils.[6] It is restricted to native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of South Georgia. [7]

However, it has been observed in some slightly disturbed areas including along the edge of open powerline corridors, a disturbed wiregrass area cleared by rootrake, and sandy roadsides.[6] A study also found frequency of G. dumosa to increase with clearcutting and thinning the overstory.[8] Overall, it is quite vulnerable to general disturbance.[9] In other areas, it can also be found in low pinelands as well as bogs and pond margins.[2] While it can be found in wet prairies, it has a higher overall preference for dry prairie habitats.[10]

G. dumosa was found to reduce its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in longleaf pine communities in South Carolina and southwest Georgia. It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished habitats that were disturbed by agricultural practices, making it a remnant woodland indicator species.[7][11][12][13][14] Additionally, it was found to decrease its cover in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods. It has also shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished flatwood habitat that was disturbed by these practices.[15] Additionally, G. dumosa was found to be a decreaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances as well as in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[16]

Associated species include Andropogon sp., Aristida stricta, Aristida sp., Sorghastrum sp., Pinus palustris, Pinus elliottii, Serenoa repens, Vaccinium darrowii, Vaccinium myrsinites, Vaccinium sp., Quercus laevis, Quercus minima, Quercus pumila, Diospyros virginiana, Actinospermum angustifolium, Leptoloma cognatum, Gaylussacia sp., Kalmia hirsuta, and others.[6]

Gaylussacia dumosa is frequent and abundant in the Panhandle Xeric Sandhills, Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands, Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands, North Florida Mesic Flatwoods, and Central Florida Flatwoods/Prairies community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[17]

Phenology

Generally, G. dumosa flowers from March to June and fruits from June until October.[1] It has been observed to flower March to May and in October with peak inflorescence in April, and fruit from April until July.[18][6]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates. [19] In particular, it has found to be dispersed by gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus).[20]

Fire ecology

Gaylussacia dumosa commonly grows in pine savannas and other habitats that are frequently burned.[6] It has been found to appear after fire disturbance in areas it was not present before.[21] It increases in frequency in response to fire, but crown height and width over time since fire does not change much.[22] However, overall canopy coverage has been seen to significantly increase in response to fire.[23] One study found the amount of cover to dramatically increase in response to fire, but as time increased since fire disturbance, the percent cover of G. dumosa to decrease; it reached its maximum cover value a couple years after fire disturbance.[24] When other disturbances, like discing and shearing and piling, are also conducted with fire disturbance, this species has been seen to decrease in frequency over time.[25] It has also been found in greater densities in burned-wiregrass habitats rather than burned-bluestem habitats.[26] It is easily ignitable due to average litter depth and bulk density which adds to the fine fuels from the plant that are able to ignite.[27] Post-fire recovery of this species is mainly through resprouting as well as clonally.[28] As for seasonality, one study found G. dumosa to benefit most from winter burn regiments rather than spring or summer burn regiments with winter burns having the highest overall occurrence and biomass of the species.[29]

Populations of Gaylussacia dumosa have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[30]

Pollination

Gaylussacia dumosa has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host a variety of species, including bees from the Apidae family such as Apis mellifera, and Bombus impatiens, sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Augochlorella aurata, and A. gratiosa, and leafcutting bees from the family Megachilidae such as Megachile brevis pseudobrevis, and M. integrella.[31]

Herbivory and toxicology

G. dumosaconsists consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for large mammals, 5-10% of the diet for small mammals, and 5-10% of the diet for various terrestrial birds.[32][33] This plant is seldom eaten by white-tailed deer.[34] Herbaceous vegetation of this species has been found in the scat of gopher tortoises (Gopherus polyphemus).[35] Fruit production becomes an important component of the diet for mammals and birds in older pine stands and plantations than young pine plantations.[36]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Gaylussacia dumosa is listed as threatened by the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, the New Hampshire Division of Forests and Lands, and the Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation. It is listed as endangered by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation and the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, and is listed as a species of special concern by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management.[4] This species should avoid soil disturbance by agriculture and clearcutting and chopping to conserve its presence in pine communities.[7][11][12][13][14][15]

Cultural use

The fruit can be eaten as a spicy snack.[37]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 15, 2019

- ↑ Levey, D. J., et al. (2016). "Disentangling fragmentation effects on herbivory in understory plants on longleaf pine savanna." Ecology 97(9): 2248-2258.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 15 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Sorrie, B. A. and A. S. Weakley 2001. Coastal Plain valcular plant endemics: Phytogeographic patterns. Castanea 66: 50-82.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: May 2019. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Edwin L. Bridges, D. Burch, S. Clawson, Andre F. Clewell, George R. Cooley, M. Davis, Patricia Elliot, Bob Fewster, J. P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, H. E. Grelen, D. Kennemore, R. Kral, Karen MacClendon, Sidney McDaniel, Marc C. Minno, R. S. Mitchell, John B. Nelson, Steve L. Orzell, Elmer C. Prichard, Gwynn W. Ramsey, Helen Roth, Annie Scmidt, Robert W. Simons, Cecil R. Slaughter, L. B. Trott, D. B. Ward, Kenneth A. Wilson, and Carroll E. Wood, Jr. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Calhoun, Clay, Columbia, Escambia, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Hamilton, Hernando, Highlands, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Manatee, Nassau, Okaloosa, Polk, St Johns, Suwannee, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, and Walton. Georgia: Thomas.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.

- ↑ Brockway, D. G. and C. E. Lewis (2003). "Influence of deer, cattle grazing and timber harvest on plant species diversity in a longleaf pine bluestem ecosystem." Forest Ecology and Management 175: 49-69.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. K., et al. (2004). "Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna." Journal of Ecology 92(3): 409-421.

- ↑ Orzell, S. L. and E. L. Bridges (2006). "Floristic composition of the south-central Florida dry prairie landscape." Florida Ecosystem 1(3): 123-133.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 9 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kay Kirkman, Jones Ecological Research Center, unpublished data, 2015.

- ↑ Carlson, J. E., E. S. Menges, and P. L. Marks. 2003. Seed dispersal by Gopherus polyphemus at Archbold Biological Station, Florida. Florida Scientist, v. 66, no. 2, p. 147-154.

- ↑ Hierro, J. L. and E. S. Menges (2002). "Fire intensity and shrub regeneration in palmetto-dominated flatwoods of central Florida." Florida Scientist 65: 51-61.

- ↑ Abrahamson, W. (1984). "Post-Fire Recovery of Florida Lake Wales Ridge Vegetation." American Journal of Botany 71(1): 9-21.

- ↑ Moore, W. H., et al. (1982). "Vegetative response to prescribed fire in a north Florida flatwoods forest." Journal of Range Management 35: 386-389.

- ↑ Abrahamson, W. G. (1984). "Species Responses to Fire on the Florida Lake Wales Ridge." American Journal of Botany 71(1): 35-43.

- ↑ Conde, L. F., et al. (1983). "Plant species cover, frequency, and biomass: Early responses to clearcutting, burning, windrowing, discing, and bedding in Pinus elliottii flatwoods." Forest Ecology and Management 6: 319-331.

- ↑ Rodgers, H. L. and L. Provencher (1999). "Analysis of Longleaf Pine Sandhill Vegetation in Northwest Florida." Castanea 64(2): 138-162.

- ↑ Behm, A. L., et al. (2004). "Flammability of native understory species in pine flatwood and hardwood hammock ecosystems and implications for the wildland-urban interface." International Journal of Wildland Fire 13: 355-365.

- ↑ Maguire, A. J., Eric S. Menges (2011). "Post-fire growth strategies of resprouting florida scrub vegetation " Fire Ecology 7(3): 12-25.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Yarrow, G.K., and D.T. Yarrow. 1999. Managing wildlife. Sweet Water Press. Birmingham.

- ↑ Harlow, R. F. (1961). "Fall and winter foods of Florida white-tailed deer." The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 24(1): 19-38.

- ↑ Carlson, J. E., et al. (2003). "Seed dispersal by Gopherus polyphemus at Archbold Biological Station, Florida." Florida Scientist 66: 147-154.

- ↑ Johnson, A. S. and J. L. Landers (1978). "Fruit production in slash pine plantations in Georgia." The Journal of Wildlife Management 42(3): 606-613.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.