Croton glandulosus

| Croton glandulosus | |

|---|---|

| |

| photo by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Euphorbiales |

| Family: | Euphorbiaceae |

| Genus: | Croton |

| Species: | C. glandulosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Croton glandulosus L. | |

| |

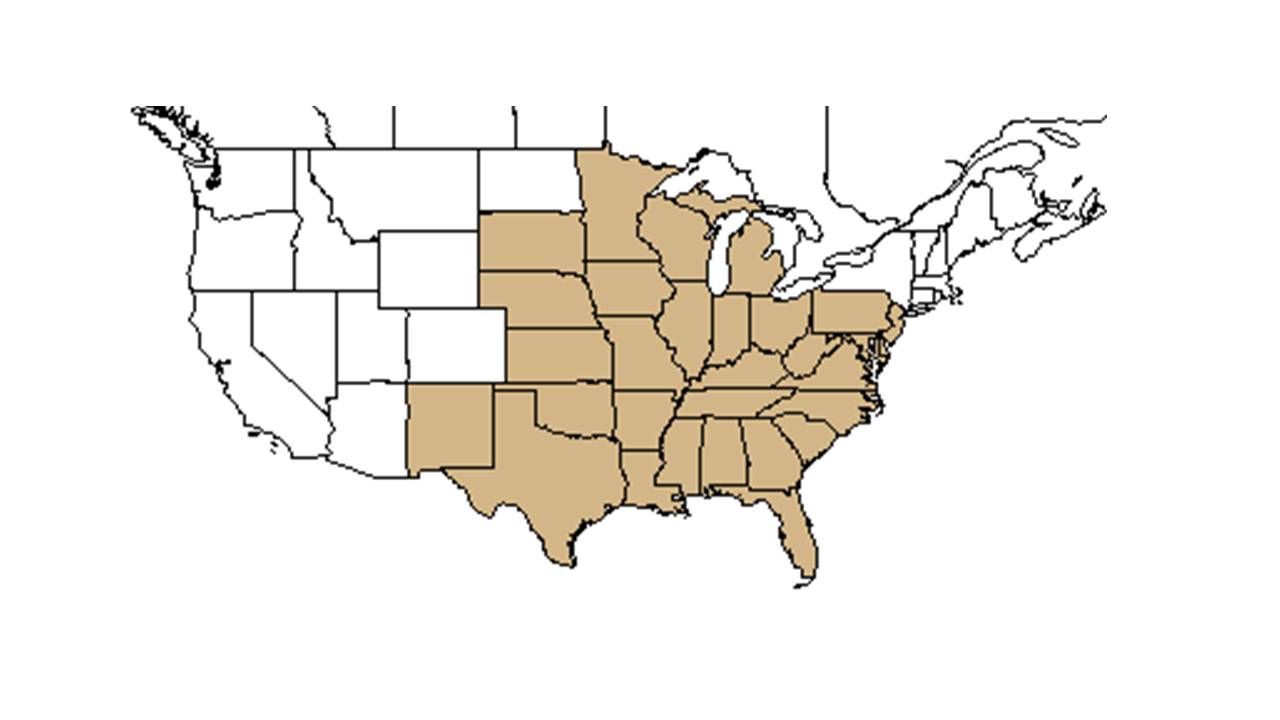

| Natural range of Croton glandulosus from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Vente conmigo, doveweed, tooth-leaved croton, sand croton, south Texas croton, northern croton

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Croton arenicola Small[1]

Varieties: Croton glandulosus Linnaeus var. lindheimeri Muller of Aargau; C. glandulosus Linnaeus var. pubentissimus Croizat; C. glandulosus Linnaeus var. arenicola Small; C. glandulosus Linnaeus var. septentrionalis Muller of Aargau; C. glandulosus var. angustifolius Muller of Aargau; C. glandulosus var. simpsonii A.M. Simpson[1]

Description

This species is an annual forb/herb and subshrub that is a member of the Euphorbiaceae family.[2] Leaves alternately arranged, serrate, and lanceolate to ovate shape. Flowers unisexual and borne on a terminal raceme. Fruit type is a capsule.[3]

Distribution

Croton glandulosus is native throughout tropical and subtropical America, but its original range is obscure.[4] It is introduced as well as native in the eastern and central United States, from Pennsylvania and New Jersey south to Florida as well as west to New Mexico, Kansas, Nebraska, South Dakota, and Minnesota. The species is also native to Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.[2]

C. glandulosus was seen to be an increaser in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[5]

Var. floridanus is endemic to Florida, and var. pubentissimus is endemic to Texas.[6]

Ecology

Habitat

It can be found in mid-grass prairie communities.[7] It can also be found in longleaf pine communities, though it is not as common since they're dominated by perennial species.[8] This species has been observed in sandy and sandy loam soils of turkey oak ridges, open fields and clearings, wet borders of swamps, cabbage palm hammocks, dunes, and the ecotone between trees and shoreline of beaches. This species also occurs in human disturbed areas such as grassy highway medians, grassy edges of parking lots, along railroad tracks, waste areas, sandy roadsides, corn fields, and citrus groves.[9] C. glandulosus was found to increase in occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia. It has shown additional regrowth in reestablished pinelands that were disturbed by agriculture.[10][11]

Associated species includes Quercus laevis, Q. geminata, Baptisia, Selaginella, Polygonella, Commelina, Pinus palustris, Haplopappus divaricatus, Pityopsis, Palofoxia, Ambrosia, and Conyza.[9]

Phenology

It is seasonal; it is mainly found from May to December, peaking in September in a study at Padre Island.[7] It has been observed flowering and fruiting June through October with peak inflorescence in June and August, and fruiting in December.[9][12]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by ants and/or explosive dehiscence. [13]

Seed bank and germination

It germinates after fire.[7]

Fire ecology

Populations of Croton glandulosus have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[14] It is included in the flowering plant survery – post burn – in Heuberger’s study[15]

Pollination

Croton glandulosus was observed at the Archbold Biological Station to be frequented by members of the Hymenoptera order. These species include thread-waisted wasps from the Sphecidae family such as Cerceris blakei and Philanthus ventilabris.[16]

Herbivory and toxicology

C. glandulosus consists of approximately 5-10% of the diet for terrestrial birds.[17] It is eaten by bobwhite quail, where one study found it to be an important food source only in 1 year old Loblolly pine (Pinus taeda) plantation stands.[18]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

C. glandulosus is listed as threatened by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. It is also considered a species that can be weedy or invasive by the Southern Weed Science Society.[2]

Cultural use

Many species of Croton can be used in medicine, but oil derived from the plant can be highly toxic for canines and cause blistering on skin.[19]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 22 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 22, 2019

- ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Sorrie, B. A. and A. S. Weakley 2001. Coastal Plain valcular plant endemics: Phytogeographic patterns. Castanea 66: 50-82.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Lonard, R. I., F. W. Judd, et al. (2004). "Recovery of vegetation following a wildfire in a barrier island grassland, Padre Island National Seashore, Texas." Southwestern Naturalist 49: 173-188.

- ↑ Simkin, S. M., W. K. Michener, et al. (2001). "Plant response following soil disturbance in a longleaf pine ecosystem." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 128: 208-218.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, G. Avery, D. Burch, Andre F. Clewell, Delzie Demaree, R. F. Doren,S. F. da Fonseca, B. J. Frier, Robert K. Godfrey, H. S. Irwin, D. Jones, Walter S. Judd, Beverly Judd, Gary R. Knight, R. Komarek, Robert Kral, Mabel Kral, Merle Kuns, O. Lakela, Robert L. Lazor, Karen MacClendon, F. Matthews, Sidney McDaniel, Richard S. Mitchell, Leon Neal, J. B. Nelson, R. A. Norris, Gwynn W. Ramsey, R. Reis dos Santos, Cecil R. Slaughter, R. Souza, V. I. Sullivan, Amanda R. Travis, Edwin L. Tyson, and D. B. Ward. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Citrus, Collier, Dade, Franklin, Hernando, Highlands, Jackson, Jefferson, Lafayette, Lake, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Martin, Nassau, Okaloosa, Pinellas, Polk, Putnam, Seminole, St. Johns, Taylor, Volusia, and Wakulla. Georgia: Thomas. Other Countries: Honduras, Bolivia, and Brazil.

- ↑ McClain, W. E., et al. (2008). "Floristic study of sand prairie-scrub oak nature preserve, Mason County, Illinois." Castanea 73(1): 29-39.

- ↑ Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson (2007). A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, south Georgia, USA. Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, Tallahassee, Tall Timbers Research Station.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 22 APR 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Everitt, J.H., D.L. Drawe, and R.I. Lonard. 1999. Field guide to the broad leaved herbaceous plants of South Texas used by livestock and wildlife. Texas Tech University Press. Lubbock.

- ↑ Sweeney, J. M., et al. (1981). Bobwhite quail food in young Arkansas loblolly pine plantations. Arkansas Experiment Station bulletin 852. Fayetteville, AR, University of Arkansas, Divisionn of Agriculture, Agricultural Experiment Station.

- ↑ Mueschner, W.C. 1957. Poisonous Plants of the United States. The Macmillan Company, New York.