Morella cerifera

| Morella cerfiera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Karan A. Rawlins, University of Georgia, Bugwood.org | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Tracheophyta- Vascular plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Myricaceae |

| Genus: | Morella |

| Species: | M. cerfiera |

| Binomial name | |

| Morella cerfiera (L.) Small | |

| |

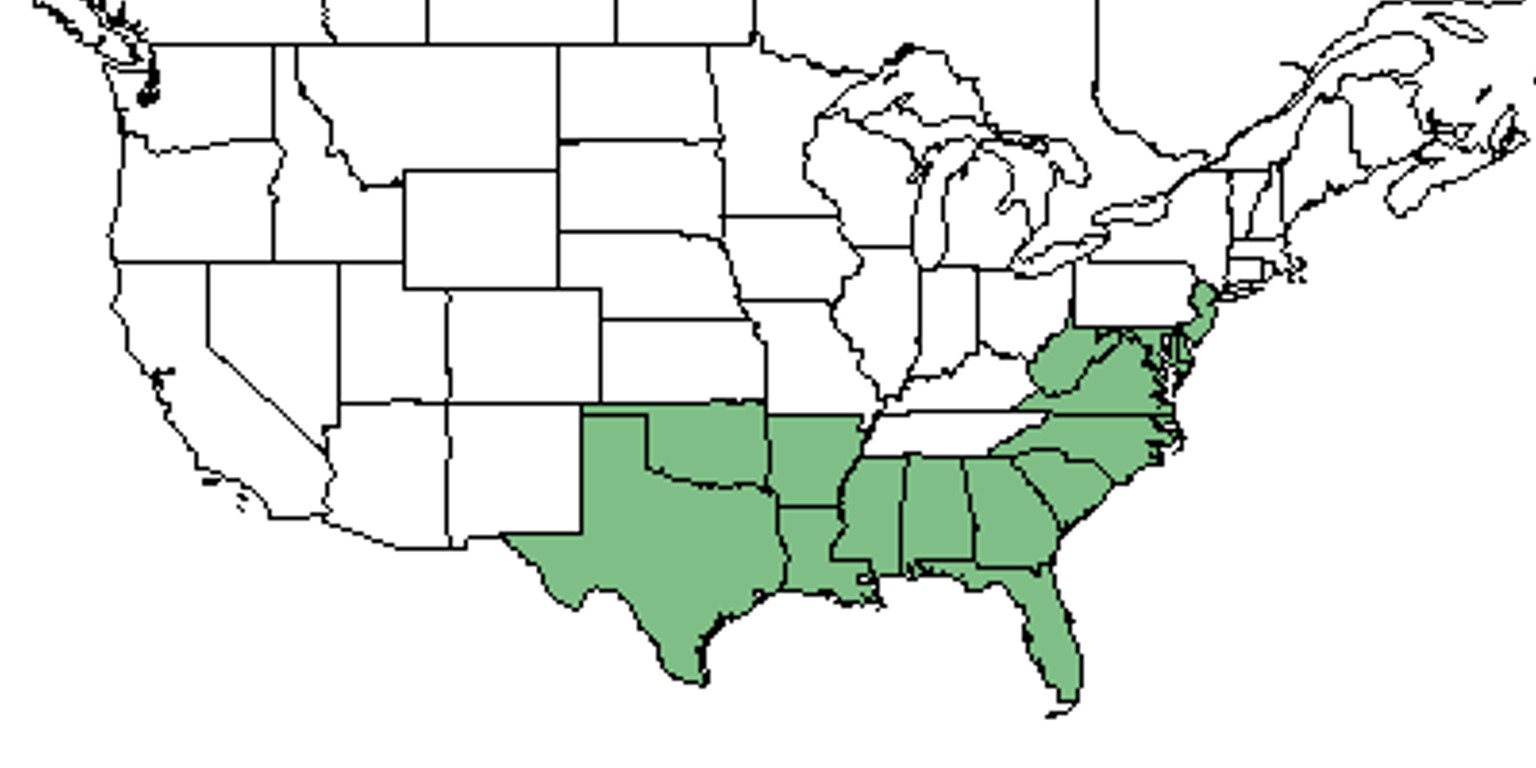

| Natural range of Morella cerfiera from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Common waxmyrtle; Southern bayberry

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Myrica cerifera L.; Myrica cerifera Linnaeus var. cerifera; Cerothamnus ceriferus (Linnaeus) Small.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

"Dioecious or monoecious shrubs or small trees, with brown to brownish-black, pubescent to glabrate twigs. Leaves deciduous or semi-evergreen, coriaceous, petiolate, exstipulate. Staminate catkins ovoid-cylindric, 0.6-2 cm long, 4-6 mm in diam.; bracteate and bracteolate; stamens 2-1, mostly 2-5. Pistillate catkins ovoid or cylindric, 5-10 mm long, deciduous-bracteate. Fruits drupaceous, white, globose, verrucose, 2.5-7 mm in diam. A taxonomically difficult group with intergrading species."[2]

"Shrub or small tree, 0.3-7 m tall. Leaves oblanceolate or elliptic, to 8 cm long and 2cm wide, heavily resinous on both surfaces, usually pubescent beneath, acute or obtuse, serrate or entire, base cuneate to attenuate, petioles to 1 cm long. Fruits 2.5-3.5 mm in diam."[2]

Distribution

Is found within the Coastal Plain and as far north as New Jersey.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

The species is naturally found in interdune swales, pocosins, brackish marshes, and other wet to moist habitats.[3] Is widely planted as an ornamental or as a landscaping shrub.[3]

M. cerifera has been found in sand barrens, mesic pine hardwood forests, turpentine glades, dry sandstone glades, pond edges, pineland bogs, pine flatwoods, maritime forests, and swamps.[4][5][6][7] It is also found in disturbed areas including highway roadsides, disturbed wetland edges, and disturbed post oak savannah.[5][6][8]

M. cerifera has shown regrowth in response to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina Coastal Plain communities, making it an indicator species for post-agricultural woodlands.[9] M. cerifera reduced its crown cover and biomass in response to heavy silviculture in north Florida.[10] It decreased its cover in response to clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods.[11] It also decreased its frequency in response to roller chopping in east Texas pinewoods.[12] This species has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished native habitats that were disturbed by these practices.[10][11][12] M. cerifera had mixed responses to clearcutting and roller chopping in north Florida and to KG blade disturbance in east Texas.[13][12] Its foliar cover is sometimes dependent on time since disturbance in north Florida flatwoods. In Texas pinewoods, the species typically decreased in frequency or was unaffected by KG blade disturbance.[13][12]

Morella cerifera is frequent and abundant in the Calcareous Savannas community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[14]

Phenology

This species flowers in April and fruits from August to October.[3]

Fire ecology

Populations of Morella cerifera have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[15][16][17]

===Herbivory and toxicology===<--Common herbivores, granivory, insect hosting, poisonous chemicals, allelopathy, etc.--> Morella cerifera has been observed to host plant bugs such as Psallus variabilis (family Miridae), and leafhoppers from the Cicadellidae family such as Empoasca deckeri and Empoasca fabae.[18]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

The wax from this plant can be used to make candles, and the leaves and berries can act as a substitute for bay leaves in food.[19]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 360. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Weakley, Alan S. Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States: Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina Herbarium (NCU). PDF. 644.

- ↑ Albion College accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: NA. States and Counties: North Carolina: Brunswick.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Angelo State University Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Paul A. Fryxell, Jeff Harper, and Stanely D. Jones, and Robert Kral. States and Counties: Florida: Pasco. Georgia: Ben Hill. Louisiana: Natchitoches. Texas: Aransas, Brazos, and Hardin.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Arizona State University Vascular Plant Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: W.R. Faircloth and A.E. Radford. States and Counties: Georgia: Brooks. South Carolina: Orangeburg.

- ↑ Catawba College Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: D. Reyes. States and Counties: North Carolina: Carteret.

- ↑ Colorado State University, Charles Maurer Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Raul Gutierrez Juanita Alejandro. States and Counties: Florida: Hillsborough.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Conde, L.F., B.F. Swindel, and J.E. Smith. (1986). Five Years of Vegetation Changes Following Conversion of Pine Flatwoods to Pinus elliottii Plantations. Forest Ecology and Management 15(4):295-300.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Stransky, J.J., J.C. Huntley, and Wanda J. Risner. (1986). Net Community Production Dynamics in the Herb-Shrub Stratum of a Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forest: Effects of CLearcutting and Site Preparation. Gen. Tech. Rep. SO-61. New Orleans, LA: U.S. Dept of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station. 11 p.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.