Eupatorium album

| Eupatorium album | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo was taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Eupatorium |

| Species: | E. album |

| Binomial name | |

| Eupatorium album L. | |

| |

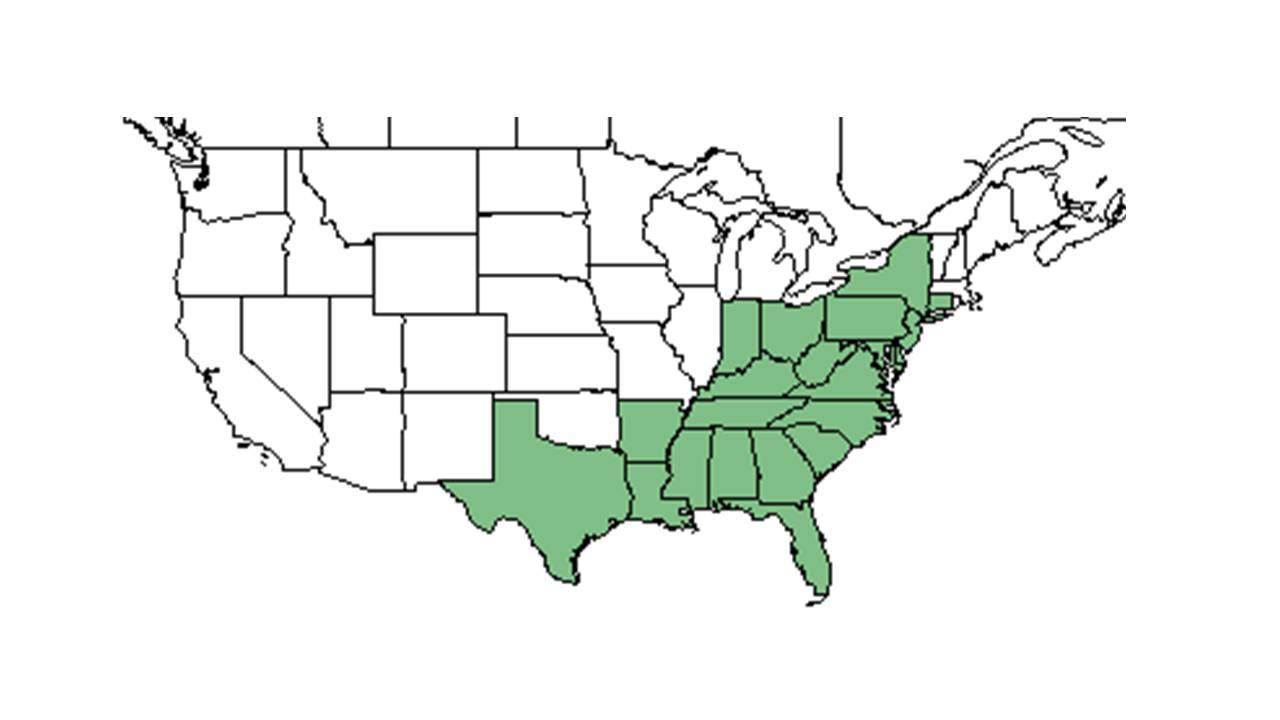

| Natural range of Eupatorium album from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: white thoroughwort; white-bracted thoroughwort

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Eupatorium album Linnaeus var. album; E. album var. glandulosum (Michaux) A.P. de Candolle

Description

A description of Eupatorium album is provided in The Flora of North America. Although the fruit is usually referred to as an achene, it is technically a cypsela.[1]

Distribution

Eupatorium album can be found from Connecticut, New York, Ohio, and Tennessee south to Florida and Louisiana.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

This species can generally be found in various dry woodlands.[2] It is found in sandhills, Longleaf pine-wiregrass savannas, evergreen scrub oak sand ridges, pine flatwoods, old fields, flatwoods, hammocks, seepage slopes, pine-palmetto flatwoods, in woods adjacent to sinkholes, and in well-drained Longleaf pinelands. It is also found in human disturbed areas such as roadsides, areas that have been clear cut, bulldozed, and in powerline corridors. It requires open to semi-shaded areas. It is associated with areas that have drying-loamy sand, wet-sandy loam, dry sand, gray-sand loam, dry-sparsely loamy sand soil types.[3] It does well in open canopy areas on longleaf pine habitats and does okay in areas that have been clear cut. [4] It is found in longleaf pine sandhill communities. [5]

E. album responds negatively to soil disturbance in South Carolina's coastal plains.[6] It also responds negatively to soil disturbance from agricultural marking it as a possible indicator species for remnant woodlands.[7][8] E. album responds positively to soil disturbance by heavy silvilculture in North Carolina.[9] It also responds positively to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[10]

Associated species include Eupatorium recurvans, E. mikanioides, E. rotundifolium, E. anomalum, E. compositifolium, E. aromaticum, Chamaecrista fasciculata, Sassafras albidum, Pteridium aquilinum, Quercus incana, Q laevis, Aristida beyrichiana, Serenoa repens, Ilex glabra, Rhynchospora, Xyris, Magnolia virginiana, E. rotundifolium, Solidago odora, Liatris gracilis, L. tenuifolia, L. elegans,Sericocarpus tortifolius, Rubus cuneufolius, Andropogon ternarius, Carphephorus corymbosus.[3]

Phenology

Generally, E. album flowers from late June until September.[2] It has been observed flowering from July to November with peak inflorescence in July.[3][11] Kevin Robertson has observed this species flower within three months of burning. KMR

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind. [12]

Fire ecology

The species can commonly be found in fire dependent habitats.[3] Generally, it increases in abundance in response to fire disturbance.[13] It flowers within three months of burning in the early spring to early summer. KMR It seems to benefit most in overall occurrence and biomass from winter burn regiments rather than spring or summer burn regiments.[14]

Conservation and management

E. album is listed as endangered by the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection and by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Nature Preserves. It is also listed as threatened by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Natural Areas and Preserves, and listed as extirpated by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.[15]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 10, 2019

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, Robert L. Lazor, John Lazor, J. P. Gillespie, R. Kral, Victoria I. Sullivan, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, Delzie Demaree, Nancy E. Jordan, R. F. Doren, R. E. Perdue, S. C. Hood, Paul L. Redfearn, Jr., R. A. Norris, and R. Komarek. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Citrus, Clay, Columbia, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Jackson, Jefferson, Lafayette, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Marion, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, Taylor, Wakulla, and Washington. Georgia: Thomas.

- ↑ Brockway, D. G. and C. E. Lewis (2003). "Influence of deer, cattle grazing and timber harvest on plant species diversity in a longleaf pine bluestem ecosystem." Forest Ecology and Management 175: 49-69.

- ↑ Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 10 MAY 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Moore, W. H., et al. (1982). "Vegetative response to prescribed fire in a north Florida flatwoods forest." Journal of Range Management 35: 386-389.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 10 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.