Asclepias tuberosa

| Asclepias tuberosa | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Gentianales |

| Family: | Asclepiadacea |

| Genus: | Asclepias |

| Species: | A. tuberosa |

| Binomial name | |

| Asclepias tuberosa (L) Brittonex Vail | |

| |

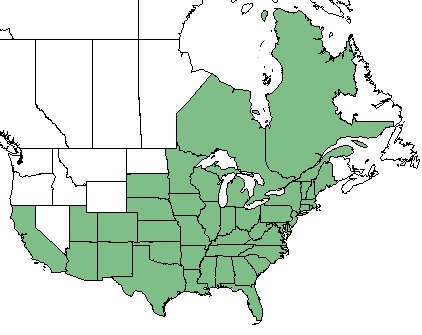

| Natural range of Asclepias tuberosa from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Names: midwestern butterfly-weed; sandhills butterfly-weed; common butterfly-weed;[1] butterfly milkweed; Rolfs' milkweed;[2] orange milkweed; pleurisy root; chigger flower[3]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Varieties: A. tuberosa var. interior; A. tuberosa var. rolfsii; A. tuberosa var. tuberosa.[1] Other sources list these three varieties as subspecies.[2]

Synonyms: A. rolfsii; A. decumbens[1]

Description

Asclepias tuberosa is a dioecious perennial forb/herb.[2] It is bushy and grows to 30-60 cm in height. Leaves are alternate, pointed, smooth on the edge, and 1.50-2.25 in (3.81-5.72 cm) long. Flat-topped clusters 2-5 in (5.1-12.7 cm) diameter contain flowers,[3] which range from a yellow to yellowish orange or a deep-orange to reddish.[1][3] Each cluster contains 88-94 flowers when grown in Michigan, but 79-87 when brought into and grown in a greenhouse.[4] Despite its common name, milkweed, it has no milky sap.[3]

Distribution

This species is found from Quebec and Maine, westward to Ontario and Minnesota, southwestward to South Dakota, Colorado, Utah, Arizona, and California, and southward to central Texas, the Gulf Coast, and peninsular Florida.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

A. tuberosa occurs in roadbanks,[1][5] dry forests, sandhills, woodland margins, roadsides, pastures,[1] hardwood hammocks[6] yellow sand sandhill savannas,[7] and scrub.[8] In southern Iowa and northern Missouri grasslands, densities were 0.3 flowering ramets Dm-2.[9]

Phenology

In the southeastern and mid-Atlantic United States, A. tuberosa flowers from May through September and fruits from August through September.[1] However, in North Port[5] and Walton County,[10] Florida, flowers have been observed blooming in April. Daylengths and cold storage lengths interact to influence the number of shoots, flowers, and length of time it takes for A. tuberosa to reach market stage.[4]

Seed bank and germination

Seed size is negatively correlated with A. tuberosa growth rates.[11]

Fire ecology

In a Minnesota oak savanna, fire frequency of 2-19 burns from 1964-1984 showed no effect on the percent coverage of A. tuberosa.[12] Similarly, flowering of A. tuberosa in an Iowa prairie was uneffected by April burning.[13]

Pollination

This species is of special value to bumble bees, honey bees, and native bees and can attract butterflies and hummingbirds as well.[3] In Arizona, the most important pollinators for A. tuberosa were Bombus sonorus, Apis mellifera, and small-sized bees. However, the presence of pollinators and their dominance varied between each year of the two year study. Other pollinators observed include Battus philenor, small-sized Lepidoptera (i.e. Hesperiidae, Nymphalidae, Pieridae), medium-sized Lepidoptera (i.e. Hesperiidae, Lycaenidae, Nymphalidae, Pieridae), medium sized bees (i.e. Anthophoridae, Megachilidae), and Archilochus alexandri.[14] The Gulf fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) has also been reported as a pollinator for A. tuberosa.[10]

Use by animals

This species composes 2-5% of the diet of some large mammals and terrestrial birds.[15] Humans will often utilize this plant in home gardens because of its color and ability to attract butterflies. Native Americans also used to chew the root as a cure for pleurisy or other pulmonary ailments. However, consuming larger quantities of any part of the plant can be toxic.[3]

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

A. tuberosa can be propagated via seeds or root cuttings. Root propagation can be performed in the fall by cutting the taproot into 2 in (5.1 cm) sections and planting each section vertically while keeping the soil moist.[3]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Weakley AS (2015) Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 13 February 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Plant database: Asclepias tuberosa. (13 February 2018) Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. URL: https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=ASTU

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Albrecht ML, Lehmann JT (1991) Daylength, cold storage, and plant-production method influence growth and flowering of Asclepias tuberosa. HortScience 26(2):120-121.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Observation by David Iannotti and identification by Edwin Bridges in North Port, Florida, April 16, 2017, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group April 16, 2017.

- ↑ Observation by Mark Reynolds in Charlotte County, FL, April 2, 2016, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group April 2, 2016.

- ↑ Observation by Edwin Bridges in Lake Wales Ridge Wildlife and Environmental Area, Carter Creek Tract, Highlands County, FL, August 26,2017, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group August 26, 2017.

- ↑ Observation by Kevin Songer in Lee County, FL, November 2, 2015, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group November 2, 2015.

- ↑ Moranz RA, Debinski DM, McGranahan DA, Engle DM, Miller JR (2012) Untangling the effects of fire, grazing, and land-use legacies on grassland butterfly communities. Biodiversity and Conservation 21(11):2719-2746.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Observation by Floyd Griffith in Walton County, FL, April 30, 2017, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group May 1, 2017. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Griffith 2017" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Gleeson SK, Tilman D (1994) Plant allocation, growth rate and successional status. Functional Ecology 8:543-550.

- ↑ Tester JR (1996) Effects of fire frequency on plant species in oak savanna in east-central Minnesota. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 123(4):304-308.

- ↑ Richards MS, Landers RQ (1973) Responses of species in Kalsow prairie, Iowa, to an April fire. Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science 80:159-161.

- ↑ Fishbein M, Venable DL (1996) Diversity and temporal change in the effective pollinators of Asclepias tuberosa. Ecology 77(4):1061-1073.

- ↑ Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.