Stipulicida setacea

| Stipulicida setacea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Shirley Denton (Copyrighted, use by photographer’s permission only), Nature Photography by Shirley Denton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Caryophyllales |

| Family: | Caryophyllaceae |

| Genus: | Stipulicida |

| Species: | S. setacea |

| Binomial name | |

| Stipulicida setacea Michx. | |

| |

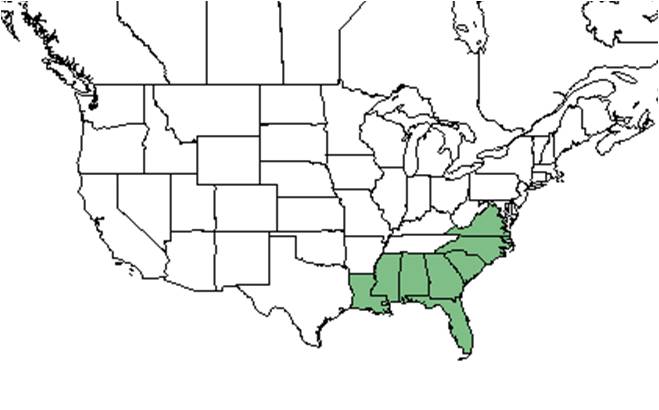

| Natural range of Stipulicida setacea from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Pineland scalypink, Coastal Plain wireplant

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Stipulicida setacea var. setacea; S. filiformis Nash; S. setacea var. filiformis (Nash) D.B. Ward

The genus name Stipulicida derives from the Greek meaning for fibers. The specific epithet setacea comes from the Latin word for bristle- which refers to the tiny leaves that resemble bristles.[1]

Description

A description of Stipulicida setacea is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

Found along the Coastal Plain from Virginia down to Florida and west to Louisiana. It is critically imperiled in Virginia and Louisiana.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain, S. setacea habitats include shrubless barrens, sandhill clearings in oak woodlands, sand pine-oak scrubs, longleaf pine-saw palmetto flatwoods, surrounding cypress wetlands, oak-hickory hammock forests, open oak-hickory-sand pine scrubs, and slash pine woodlands bordering tidal marshes. It occurs in disturbed areas such as powerline corridors, grassy roadsides, sandy old fields, parking areas, moist banks of drainage canals, and a pineapple field. Soil types include loamy sand, sand, and sandy peat. Associated species include Lupinus diffusus, Arenaria caroliniana, Opuntia, Parnoychia erecta, Polygonella robusta, Helianthemum, Vaccinium, and Crataegus.[3]

Phenology

S. setacea has white flowers, usually in clusters of three; with five petals, three stamen, and three lobed ovaries.[3] The flowers are not notched at the tips, unlike many members of this family.[4] The fruit is a small capsule with a small yellowish seed. Flowers March through June and fruits May through August.[3]

Seed dispersal

Seeds lack obvious dispersal mechanisms and is a poor disperser.[5] According to Kay Kirkman, a plant ecologist, this species disperses by gravity. [6]

Seed bank and germination

It has been observed that the seed bank after fire in the Florida rosemary scrub was dominated by S. setacea.[7][8] Carrington (1997) observed there to be more seeds present in the bank than adults in the Florida rosemary scrub.

Fire ecology

S. setacea is a seeder species that occasionally resprouts after fire.[5] Post-fire, it has been observe to dominate the seed bank in the Florida rosemary scrub.[7] It has been observed growing in burned pinewoods.[3]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Stipulicida setacea at Archbold Biological Station: [9]

Halictidae: Lasioglossum nymphalis

Megachilidae: Anthidiellum notatum rufomaculatum

Vespidae: Leptochilus krombeini, Microdynerus monolobus

Conservation and management

Threats include shoreline and barrier island erosion and fire exclusion. Beneficial management practices include shoreline and island stabilization and prescribed burning or mowing.[4]

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ [[1]]Alabama Plants. Accessed: March 17, 2016

- ↑ [[2]]NatureServe. Accessed: March 17, 2016

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: November 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Leonard J. Brass, James Buckner, Delzie Demaree, R.B. Channel, George R. Cooley, A.H. Curtiss, Wilbur H. Duncan, Bob Fewster, Angus Gholson, Robert K. Godfrey, H.A. Hespenheide, Edwin Keppner, Brian R. Keener, Robert Kral, S.W. Leonard, Sidney McDaniel, Marc Minno, John B. Nelson, Elmer C. Prichard, A.E. Radford, Paul Redfearn, William Reese, Annie Schmidt, Robert Simons, Cecil R. Slaughter, John K. Small, Wayne K. Webb, R.L. Wilbur, Kenneth A. Wilson, Carroll E. Wood Jr.. States and Counties: Alabama: Autauga, Baldwin, Henry Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Escambia, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Highlands, Hillsborough, Holmes, Indian River, Lee, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Marion, Martin, Osceola, Palm Beach, Polk, St. Lucie, St. Johns, Volusia, Wakulla,Walton, Washington. Georgia: Ben Hill, Laurens, McDuffie, Richmond, Wheeler. Mississippi: Jackson. North Carolina: Bladen, Craven, Moore, Robeson. South Carolina: Lexington, Richland. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 [[3]]Accessed: March 17, 2016

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Dee, J. R. and E. S. Menges (2014). "Gap ecology in the Florida scrubby flatwoods: effects of time-since-fire, gap area, gap aggregation and microhabitat on gap species diversity." Journal of Vegetation Science 25(5): 1235-1246. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "dee" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Kay Kirkman, unpublished data, 2015.

- ↑ Carrington, M. E. (1997). "Soil Seed Bank Structure and Composition in Florida Sand Pine Scrub." The American Midland Naturalist 137(1): 39-47.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.