Smilax glauca

Common name: whiteleaf greenbriar[1], wild sarsaparilla[1], cat greenbriar[2]

| Smilax glauca | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Gwaltney hosted at Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Smilacaceae |

| Genus: | Smilax |

| Species: | S. glauca |

| Binomial name | |

| Smilax glauca Walter | |

| |

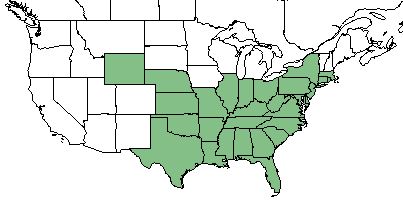

| Natural range of Smilax glauca from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: none

Varieties: S. glauca var. leurophylla Blake

Description

S. glauca is a perennial shrub/vine of the Smilacaceae family native to North America.[2]

Distribution

S. glauca is found in the southeastern corner of the United States from Wyoming to Massachusetts.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

S. glauca proliferates in a wide variety of upland and wetland habitats.[1]

S. glauca has been resistant to growth in reestablished pine woodland habitats that were disturbed by agriculture in South Carolina coastal plain communities, making it a possible indicator species for remnant woodlands.[3]

However, in other areas the species was unaffected by agriculture in South Carolina pine habitats.[4]

It exhibits no response to soil disturbance by improvement logging in Mississippi.[5] S. glauca also does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods forests.[6]

Specimens have been collected from drying loamy sand, mesic woodland, cedar swamp, and bottomland hardwood.[7]

Smilax glauca is frequent and abundant in the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands and Upper Panhandle Savannas community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[8]

Phenology

S. glauca has been observed to flower April through May.[9]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[10]

Fire ecology

S. glauca is not fire resistant, but has a high fire tolerance[2] as seen in populations that have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[11][12][13]

S. glauca has high palatability for browsing animals, but low palatability for grazing animals.[2]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

There are many species of Smilax and it is thought they can all be used in similar ways. Historically, the roots were harvested and prepared in a red flour or a thick jelly that could be used in candies and sweet drinks. Our first known written account of using the plant roots to make this jelly is from the journal of Captain John Smith in 1626. Other travelers throughout US history have made note of the uses of Smilax plants. We know the flour was used in breads and soups, and that a drink very similar to Sarsaparilla could be prepared. The shoots of this particular species are also edible without cooking.[14]

The jelly from this particular species comes out honey-colored.[15]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=SMGL

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ McComb, W.C. and R.E. Noble. (1982). Response of Understory Vegetation to Improvement Cutting and Physiographic Site in Two Mid-South Forest Stands. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society 47(1):60-77.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, R. Komarek, Andre F. Clewell, Chris Cooksey, Cecil SLaughter, Marc Minno, Bob Fewster, William Platt, Richard Carter, M. Darst, H. Light, L. Peed. States and counties: Florida (Levy, Washington, Flagler, Leon, Calhoun, Wakulla) Georgia (Thomas, Grady, Taylor)

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ PNelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 29 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.