Nothoscordum bivalve

| Nothoscordum bivalve | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo from the Illinois Wildflowers Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Liliaceae |

| Genus: | Nothoscordum |

| Species: | N. bivalve |

| Binomial name | |

| Nothoscordum bivalve L. | |

| |

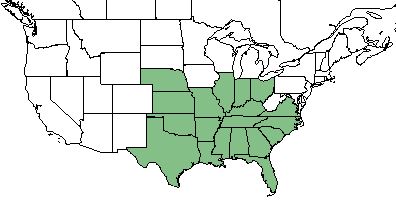

| Natural range of Nothoscordum bivalve from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: Grace garlic; False garlic;[1] Crowpoison[2]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Allium bivalve (Linnaeus) Kuntze.[3]

Varieties: none.[3]

Description

Nothoscordum bivalve is a bulbous[4] monoecious perennial forb/herb.[2] It is an onion-like plant but typically lacks an odor.[1]

Distribution

This species is found from southeastern Virginia, westward to southern Ohio and Kansas, southward to central peninsular Florida, Texas, and South America.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

N. bivalve occurs around granite flatrocks, in various glades and barrens, open woodlands, fields,[1][4] disturbed soils, low sandy woods, meadows, prairies, parking strips of towns, and rocky glades of limestone, chert, granite or sandstone. N. bivalve has additionally been found in swamp forests, pine-oak sandhills, oak woodlands, and pinelands.[5] It is also found in disturbed areas including roadsides, along fences, and burned pine savannah.[5] Associated species: C. atlantica ssp. capillacea, Rhynchospora miliacea, Allium canadense, and Dryopteris.[5]

In Tennessee cedar (limestone) glades, N. bivalve is most abundant where soil is 10-15 cm deep. It can be found in glades that are flooded during winter and early spring and in those that are unflooded. During summer months in this habitat, soil moisture is frequently below the wilting coefficient.[4]

Associated species in Tennessee glades include Erigeron strigosus, Hypericum sphaerocarpum, Isanthus brachiatus, Isoetes butleri, Ophioglossum engelmanni, Petalostemon gattingeri, Psoralea subacaulis, Ruellia humilis, Satureja glabella, Scutellaria parvula, Senecio smallii, and Sporobolus vaginiflorus.[4]

Phenology

Seeds emerge from the soil in Tennessee glades during late February or early March and are fully elongated by late March and early April. Flowering here begins in early April, is in full flower by late April to early May, and ends by mid-May. Green fruits and seeds occur from May first through the third week of May and ripe seeds occur from mid to late May. However, wet environments can shift the fruiting further into early to mid-June. Seeds are dispersed within 1-2 weeks of ripening. As seeds ripen, the stem turns yellow and dies about the time of seed dispersal. Bulblets are produced at the base of the plant between April and May. However, bulblets and/or seeds do not always occur, could both occur, or just one or the other. Roots also start dying at the same time as bulblets and completely die when the summer dry period sets in. In autumn, new roots grow that typically persist through winter. New leaves are also produced during autumn once soil moisture conditions become favorable. Autumn leaves die by mid-November, although it produces 1+ leaves that remain under the soil surface until late February or early March. Seed germination occurs from late March to mid-April. Warmer temperatures appear to trigger bulblet growth of roots and shoots. Root growth starts before the shoots and shoot growth seems more responsive to the temperature regime than roots. The optimal regime was a 30/15 °C 12/12 hr alternating interval.[4]

In the southeastern and mid-Atlantic United States, N. bivalve flowers from mid-March through mid-May and in September through December. Fruiting occurs in May through June and from October through January.[1] For the Florida panhandle, reports of flowering primarily occur from January through May, peaking between February and April. Flowering has also been observed in September through November, but in reduced numbers compared to the spring.[6]

Seed bank and germination

A period of stratification is required to end seed dormancy. Germination was most successful in a 14-week dark stratification, rather than light or 7-week stratification, and colder temperatures (15/6 °C 12/12 hr alternating intervals rather than 20/10 or 30/15 °C).[4]

Fire ecology

In Illinois barrens, N. bivalve was one of the species present before a burn; but absent afterward; this suggests it is intolerant of fire.[7] However, populations on the Wade Tract of south Georgia have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[8]

Pollination and use by animals

Two hoverfly species are known to visit and help pollinate N. bivalve. These include Sphaerophoria contiqua and Toxomerus marginatus.[9] Additionally, this species is visited by ground-nesting bees from the Andrenidae family such as Panurginus polytrichus.[10] Herbivory by grazers is low for this species,[11] but trace amounts have been found in white-tailed deer rumen of southern Texas.[12] Relative abundance peaks in properly grazed prairies and overgrazed but uneroded prairies.[11] Seeds may also be consumed trace quantities by bobwhite and scaled quail in southwest Texas.[13]

Diseases and parasites

Fungal parasites have been observed on N. bivalve, including Uromyces primaverilis ssp. nothoscordi.[14]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley AS (2015) Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 08 February 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Baskin JM, Baskin CC (1979) The ecological life cycle of Nothoscordum bivalve in Tennessee cedar glades. Castanea 44(4):193-202

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: L.C. Anderson, Robert K. Godfrey, Karen MacClendon, and Travis MacClendon. States and counties: Florida: Calhoun, Liberty, and Wakulla. Georgia: Grady.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 8 FEB 2018

- ↑ Heikens AL, West KA, Robertson PA (1994) Short-term response of chert and shale barrens vegetation to fire in southwestern Illinois. Castanea 59(3):274-285.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Tooker JF, Hauser M, Hanks LM (2006) Floral hosts plants of Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) of central Illinois. Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99(1):96-112.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Smith CC (1940) The effect of overgrazing and erosion upon the biota of the mixed-grass prairie of Oklahoma. Ecology 21(3):381-397.

- ↑ Everitt JH, Drawe DL (1974) Spring food habits of white-tailed deer in the south Texas plains. Journal of Range Management 27(1):15-20

- ↑ Campbell-Kissock L, Blankenship LH, Stewart JW (1985) Plant and animal foods of bobwhite and scaled quail in southwest Texas. The Southwestern Naturalist 30(4):543-553.

- ↑ Savile DBO (1961) Some fungal parasites on Liliaceae. Mycologia 53(1):31-52.