Erigeron strigosus

| Erigeron strigosus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Erigeron |

| Species: | E. strigosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Erigeron strigosus Muhl. ex Willd. | |

| |

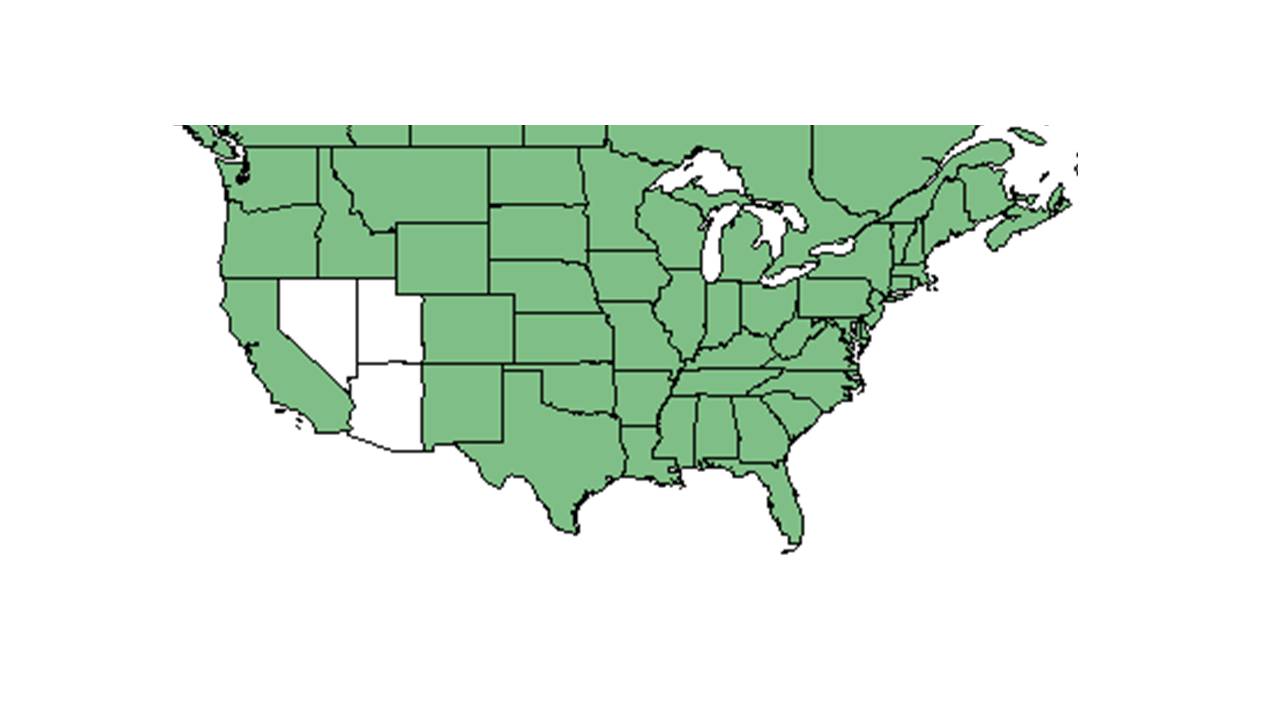

| Natural range of Erigeron strigosus from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: prairie fleabane; common eastern fleabane; common rough fleabane

Contents

[hide]Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Erigeron strigosus Muhlenberg ex Willdenow[1]

Varieties: Erigeron strigosus Muhlenberg ex Wildenow var. strigosus; Erigeron strigosus Muhlenberg ex Willdenow var. septentrionalis (Fernald & Wiegand) Fernald; Erigeron strigosus var. beyrichii[1]

Description

A description of Erigeron strigosus is provided in The Flora of North America.

Distribution

Generally, E. strigosus can be found across the United States and Canada in all provinces except the northern provinces, and all states but Alaska, Hawaii, Nevada, Utah, and Arizona.[2] E. strigosus var. calcicola is found in the central basin of Tennessee, northwest Georgia, and northern Alabama. E. strigosus var. dolomiticola is endemic to Bibb county in Alabama. E. strigosus var. septentrionalis is scattered across northern North America, south to New York, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Wyoming, and California. Lastly E. strigosus var. strigosus is distributed from Nova Scotia west to Washington state, and south to central peninsular Florida as well as Texas.[1] Apomictic (reproduce asexually) populations usually have wider distributions than sexual populations.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

E. strigosus var. calcicola can be found in limestone glades, var. dolomiticola can be found in calcareous Ketona glades, var. septentrionalis can be found in roadsides and other disturbed areas, and var. strigosus can be found in open woodlands as well as roadsides and other disturbed areas.[1] In the Coastal Plain, E. strigosus can occur in upland old fields, sandy floodplains, turkey oak forests, lake shores, sandhill scrub oak-wiregrass communities, open oak woods, boggy slopes of longleaf pine savannas, and open limestone glades. In human disturbed areas it has been found along sandy roadsides, vacant lots, a disturbed sandhill growing with planted Pinus palustris and disturbed longleaf pine restoration sites. Soils include sand, sandy clay, loamy sand and sandy loam. [4] E. strigosus was found to be in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[5]

Associated species include Liatris, Panicum, Leptoloma cognata, Baptisia megacarpa, Festuca, Piptochaetium, Verbena, Pinus palustris, Hymenopappus scabiosaeus, Phlox floridana, Stillingia sylvatica, Asimina longifolia var. spathulata, Lactuca graminifolia, Stylosanthes biflora, Erigeron strigosa, Baptisia lanceolata, Hedyotis crassifolia, Pterocauloon undulatum, Asclepias humistrata, Quercus hemisphaerica, Rhynchospora divergens, and Allium canadense. [4]

Phenology

E. strigosus has been observed flowering in February through October with peak inflorescence in May.[6][4] For the varieties, var. calcicola flowers from April or May until October, var. dolomiticola flowers from late May until October, and var. strigosus flowers from late April until October.[1] Overall, it begins flowering in March, with peak inflorescence in April and May, and sporadically flowers until October to early November, although it can flower outside of this normal time period.[3]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind.[7]

Seed bank and germination

It is commonly found in the seed bank in the areas it is found, and germination rates increase after a fire disturbance. However, germination rates were seen to decrease with annual fire disturbance compared to four year burn regiments.[8]

Fire ecology

Generally, E. strigosus significantly increases abundance in response to fire disturbance,[9] and populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[10][11] It commonly germinates in response to fire disturbance, and germination rates increase with fire disturbance rather than with no disturbance.[8] Increasing fire frequency overall has a positive affect on this species.[12] As well, E. strigosus benefits the most from a high fire return interval.[13] It also benefits more from springtime burn regiments rather than summertime burn regiments.[14]

Pollination

Erigeron strigosus has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Agapostemon splendens, Augochlorella aurata, Halictus poeyi and Lasioglossum placidensis[15] Other pollinators of E. strigosus include Dialictus placidensis, Halictus ligatus, Ceratina calcarata, Ceratina dupla, Ceratina strenua, Hylaeus mesillae, Hylaeus modestus, Augochloropsis sumptuosa and Lasioglossum pilosum.[16][17] It is also pollinated by the Karner blue butterfly (Lycaeides melissa samuelis).[18] Additionally, E. strigosus has been observed to host aphids such as Uroleucon sp. (family Aphididae), ground-nesting bees from the family Andrenidae such as Andrena brevipalpis, Andrena thaspii and Andrena wilkella, bees from the Apidae family such as Epeolus pusillus and Nomada articulata, plasterer bees from the Colletidae family such as Colletes mandibularis, Colletes simulans and Hylaeus coloradensis, sweat bees from the family Halictidae such as Agapostemon virescens, Augochlora pura, Halictus confusus, Halictus parallelus, Lasioglossum cinctipes, Lasioglossum hitchensi, Lasioglossum imitatum, Lasioglossum truncatum and Lasioglossum zonulum, true bugs such as Xyonysius californicus (family Lygaeidae), leafcutting bees from the family Megachilidae such as Heriades variolosa, Megachile pugnata, and Stelis lateralis, plant bugs such as Lygus lineolaris (family Miridae), and tree bugs from the family Membracidae such as Campylenchia latipes, Campylenchia sp.and Spissistilus festinus.[19] For grassland butterfly communities, E. strigosus is a very important nectar source due to its high density of flowering ramets compared to other flowering species in the same community.[20] As well, it is thought to be pollinated by flies in the Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) families.[21] This species is considered to be of special value since it attracts a large number of native bees for pollination.[22]

Herbivory and toxicology

E. strigosus consists of approximately 5-10% of the diet for various large mammals.[23] In the springtime, it is foraged by white-tailed deer.[24] This species supports conservation biological control through attracting predatory or parasitoid insects that in turn prey upon pest insects.[22]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

This species is considered to be weedy or invasive in Nebraska and the Great Plains region of the United States.[2]

For restoring prairie sites, E. strigosus can be utilized to help restore the community, and has been seen to persist in the seed bank as a site is being restored.[25]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 8 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.0 3.1 Noyes, R. D., et al. (2006). "Sexual and apomictic prairie fleabane (Erigeron strigosus) in Texas: geographic analysis and a new combination (Erigeron strigosus var. traversii, Asteraceae)." SIDA Contributions to Botany 22(1): 265-276.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: October 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Andre F. Clewell, R.F. Doren, Patricia Elliot, Richard Gaskalla, J.P. Gillespie, R. K. Godfrey, H.E. Grelen, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, E.M. Hodgson, C. Jackson, Ann F. Johnson, J.M. Kane, Gary R. Knight, R. Komarek, R. Kral, Richard Mitchell, R. A. Norris, Gwynn W. Ramsey, Paul L. Redfearn Jr. , Bian Tan, L.B. Trott, B. L. Turner. States and Counties: Alabama: Limestone. Florida: Calhoun, Columbia, Franklin, Gadsden, Hamilton, Leon, Liberty, Jackson, Jefferson, Madison, Marion, Nassau, Okaloosa, Polk, Putnam, Suwannee, Union, Wakulla. Georgia: Grady, Thomas. Louisiana: Caldwell. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- Jump up ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- Jump up ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 9 DEC 2016

- Jump up ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Abrams, M. (1988). "Effects of Burning Regime on Buried Seed Banks and Canopy Coverage in a Kansas Tallgrass Prairie." The Southwestern Naturalists 33(1): 65-70.

- Jump up ↑ Taft, J. B. (2003). "Fire effects on community structure, composition, and diversity in a dry sandstone barrens." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 130: 170-192.

- Jump up ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- Jump up ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- Jump up ↑ Burton, J. A. (2009). Fire frequency effects on vegetation of an upland old growth forest in eastern Oklahoma. Environmental Science. Stillwater, Oklahoma, Oklahoma State University. Bachelor: 78.

- Jump up ↑ Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.

- Jump up ↑ Towne, E. G. and K. E. Kemp (2008). "Long-term response patterns of tallgrass prairie to frequent summer burning." Rangeland Ecology & Management 61: 509-520.

- Jump up ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- Jump up ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).

- Jump up ↑ Grundel, R., et al. (2011). "A survey of bees (Hymenoptera: Apoidea) of the Indiana Dunes and Northwest Indiana, USA." Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 84(2): 105-138.

- Jump up ↑ Grundel, R., et al. (2000). "Nectar plant selection by the Karner blue butterfly (Lycaeides melissa samuelis) at the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore." The American Midland Naturalist 144(1): 1-10.

- Jump up ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- Jump up ↑ Moranz, R. A., et al. (2012). "Untangling the effects of fire, grazing, and land-use legacies on grassland butterfly communities." Biodiversity and Conservation 21(11): 2719-2746.

- Jump up ↑ Tooker, J. F., et al. (2006). "Floral host plants of Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) of central Illinois." Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99(1): 96-112.

- ↑ Jump up to: 22.0 22.1 [[2]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 9, 2019

- Jump up ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- Jump up ↑ Gee, K. L., et al. (1994). White-tailed deer: their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.

- Jump up ↑ Rosburg, T. R. and M. Owens (2004). The seed bank of a reconstructed prairie. Proceeding of the North American Prairie Conferences.