Smilax bona-nox

Common Names: Saw Greenbrier[1], Catbrier, Bullbrier[2]

| Smilax bona-nox | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Gwaltney hosted at Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida - Moncots |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Smilacaceae |

| Genus: | Smilax |

| Species: | S. bona-nox |

| Binomial name | |

| Smilax bona-nox L. | |

| |

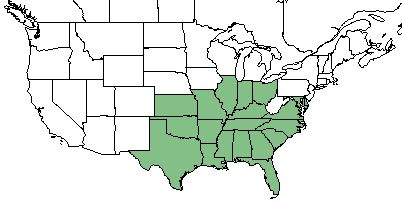

| Natural range of Smilax bona-nox from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym: none

Variety: S. bona-nox var. littoralis (Coker ex Sorrie); S. bona-nox var. exauriculata (Fernald), S. bona-nox var. hederifolia (Beyrich) Fernald

Description

Smilax bona-nox is a perennial shrub/vine of the Smilacaceae family that is native to North America.[1]

Smilax bona-nox does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its rhizomes.[3] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 60.3 mg/g (ranking 68 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 65.7% (ranking 85 out of 100 species studied).[3]

Distribution

S. bona-nox is found in the southeastern United States; Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, Ohio, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, Illinois, Alabama, Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Texas.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Common habitats for S. bona-nox include wetland and upland habitats, dunes, and maritime thickets and forests.[4] S. bona-nox can grow in a variety of soils, coarse, medium, and fine textures.[1] It has a medium tolerance to drought and a high tolerance for shade.[1] Habitats that specimens have been collected from include moist loamy soil near creeks, edges of msic woodland, and lower tidal swamps.[5]

Phenology

S. bona-nox has been observed flowering in April.[6]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[7]

Fire ecology

S. bona-nox has a high tolerance to fire.[1]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

There are many species of Smilax and it is thought they can all be used in similar ways. Historically, the roots were harvested and prepared in a red flour or a thick jelly that could be used in candies and sweet drinks. Our first known written account of using the plant roots to make this jelly is from the journal of Captain John Smith in 1626. Other travelers throughout US history have made note of the uses of Smilax plants. We know the flour was used in breads and soups, and that a drink very similar to Sarsaparilla could be prepared.[8]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 USDA Plant Database

- ↑ Gee, K. L., et al. (1994). White-tailed deer: their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R>K.Godfrey, Chris Cooksey, R. Komarek, J.M. Kane, Herbert Kessler, Tina Kessler, William Platt, M. Darst, L. Webster, L.Peed. States and counties: Florida (Wakulla, Leon, Holmes, Liberty, Levy) Georgia (Thomas, Grady)

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 29 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.