Chrysopsis mariana

| Chrysopsis mariana | |

|---|---|

| |

| photo by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Chrysopsis |

| Species: | C. mariana |

| Binomial name | |

| Chrysopsis mariana (L.) Elliott | |

| |

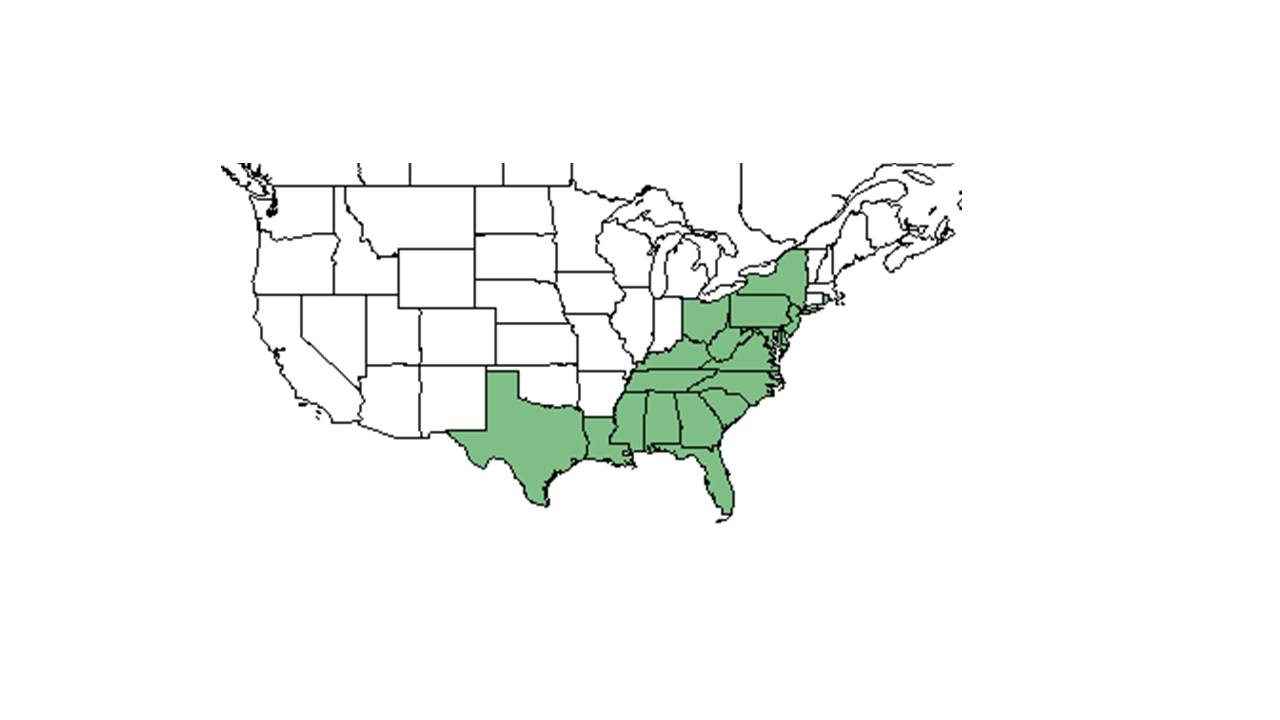

| Natural range of Chrysopsis mariana from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Maryland Golden-aster

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Heterotheca mariana (Linnaeus) Shinners.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

A description of Chrysopsis mariana is provided in The Flora of North America. Remains in a low and sturdy rosette until it flowers in the late summer with clusters of yellow aster-like flowers. Foliage is woolly when young, and becomes smoother as it ages.[2]

Distribution

C. mariana is native to the eastern and southeastern United States, ranging from New York and Ohio south to Florida and as far west as Louisiana and Texas.[3] Populations of differing ploidy are distributed in different areas; diploids can be found in the Florida panhandle and central peninsula, tetraploids can be found in northeast Florida and the north peninsula, hexaploids can be found over the rest of the native distribution besides Florida except for the north central panhandle, and octoploids can be found along the northeast coastline of Florida either near or on Merritts Island.[4]

Ecology

Habitat

It can live in humid and mild climates with plenty of rainfall throughout the year. It can tolerate temperatures ranging from 3 to 33 degrees Celsius. It is found in abundance in longleaf pine communities and also has grown in sand ridges and live oak floodplain forests.[5][6] Chrysopsis mariana is restricted to native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of South Georgia.[7] It has been observed to grow in open and shaded environments in moist loamy sands. It's been found in disturbed areas such as sandy clearings within pine-hardwood forests, clear cut pine plantations, and along dirt roads.[6] It is listed as an obligate upland species, and almost never occurs in wetlands.[3] C. mariana is also considered an indicator species of the Florida panhandle silty longleaf woodlands, and a potential indicator of longleaf pine savanna native ground-cover.[8][9] When exposed to soil disturbance by military training in West Georgia, C. mariana responds negatively by way of absence.[10] C. mariana responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.[11]

Associated species include longleaf pine, turkey oak, and live oak.[6]

Chrysopsis mariana is frequent and abundant in the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type and is an indicator species for the Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[12]

Phenology

C. mariana flowers in the fall.[13]It has also been observed in north Florida to flower January to March, May, July, October, and November.[14] It fruits in May and November.[6]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind. [15]

Fire ecology

It is tolerant of fire.[5] C. mariana tends to appear in large numbers after a site is burned.[6] One study found it to be a major species in frequency following burns, and was the greatest biomass after a spring burn, rather than a winter or summer burn. However, overall frequency of the species was not affected by seasonality of fire.[5]

Pollination and use by animals

Chrysopsis mariana has been observed to host ground-nesting bees from the Andrenidae family such as Andrena fulvipennis and Perdita boltoniae, as well as leafcutting bees such as Coelioxys sayi (family Megachilidae), and bees from the family Apidae such as Triepeolus atripes and T. pectoralis.[16] Additionally, C. mariana hosts aphids such as Uroleucon sp. (family Aphididae). C. mariana consists of about 2-5% of the diet of large mammals.[17]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

It is listed as endangered by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, and is listed as threatened by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management.[3]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 5, 2019

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 5 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Kush, J. S., R. S. Meldahl, et al. (1999). "Understory plant community response after 23 years of hardwood control treatments in natural longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) forests." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 29: 1047-1054. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Kush" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Bill Boothe, Kathleen Craddock Burks, R.K. Godfrey, Ann F. Johnson, R. Komarek, R L Lazor, John Morrill, R. A. Norris, Ginny Vail, and Jean W. Wooten. States and Counties: Florida: Calhoun, Franklin , Gulf , Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Liberty, Taylor, Union, and Wakulla. Georgia: Thomas.

- ↑ Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson (2007). A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, south Georgia, USA. Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, Tallahassee, Tall Timbers Research Station.

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. K., K. L. Coffey, et al. (2004). "Ground cover recovery patterns and life-history traits: implications for restoration obstacles and opportunities in a species-rich savanna." Journal of Ecology 92(3): 409-421.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 7 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.