Difference between revisions of "Galactia volubilis"

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

The amount of ''G. volubilis'' decreased after a spring burn, summer burn, and in the control plot<ref name="Cushwa et al 1970">Cushwa, C. T., M. Hopkins, et al. (1970). Response of legumes to prescribed burns in loblolly pine stands of the South Carolina Piedmont. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SE-140: 6.</ref> | The amount of ''G. volubilis'' decreased after a spring burn, summer burn, and in the control plot<ref name="Cushwa et al 1970">Cushwa, C. T., M. Hopkins, et al. (1970). Response of legumes to prescribed burns in loblolly pine stands of the South Carolina Piedmont. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SE-140: 6.</ref> | ||

“Results from previous studies<ref>Cushwa, C. T., Czuhai, Eugene, Cooper, R. W., and Julian, W. H. | “Results from previous studies<ref>Cushwa, C. T., Czuhai, Eugene, Cooper, R. W., and Julian, W. H. | ||

| − | 1969. Burning clearcut openings in Ioblolly pine to improve wildlife habitat. Ga. Forest Res. Count. Res. Pap. 61, 5 pp. Cushwa, C. T. and Redd, J. B. 1966. One prescribed burn and its effects on habitat of the Powhatan Game Management Area. Southeast. Forest Exp. %a., U. S. Forest Serv. Res. Note SE-61, 2 pp.</ref> indicate that leguminous plants and seed respond best to “hot” fires such as those in which a high proportion of the ground fuel is consumed. Laboratory tests<ref>Cushwa, C. T., Martin, R. E., and Miller, R. L. 1968. The effects of fire on seed germination. J. Range Manage. 21: 250-254. M a r t i n , R . E., a n d C u s h w a , C . T. 1966. Effects of heat and moisture on leguminous seed. Fifth Annu. Tall Timbers Fire Ecol. Conf. Proc. 1966: 159-175.</ref> have also shown that seed from several leguminous species germinate best after scarification with moist heat at temperatures near | + | 1969. Burning clearcut openings in Ioblolly pine to improve wildlife habitat. Ga. Forest Res. Count. Res. Pap. 61, 5 pp. Cushwa, C. T. and Redd, J. B. 1966. One prescribed burn and its effects on habitat of the Powhatan Game Management Area. Southeast. Forest Exp. %a., U. S. Forest Serv. Res. Note SE-61, 2 pp.</ref> indicate that leguminous plants and seed respond best to “hot” fires such as those in which a high proportion of the ground fuel is consumed. Laboratory tests<ref>Cushwa, C. T., Martin, R. E., and Miller, R. L. 1968. The effects of fire on seed germination. J. Range Manage. 21: 250-254. M a r t i n , R . E., a n d C u s h w a , C . T. 1966. Effects of heat and moisture on leguminous seed. Fifth Annu. Tall Timbers Fire Ecol. Conf. Proc. 1966: 159-175.</ref> have also shown that seed from several leguminous species germinate best after scarification with moist heat at temperatures near 80 degrees C., a situation requiring a hot fire. The response of the leguminous plants and seed in this study, therefore, would probably have been greater if the pine stands had been burned with more intense fires. Nevertheless, further work will be necessary before we can make final conclusions about the value of prescribed burning to quail and other wildlife in the 2.5 million acres of pine in the South Carolina Piedmont.”<ref name="Cushwa et al 1970"/> |

G. volubilis had the greatest coverage on the January-burned plots in the loblolly-shortleaf pine communities of the Alabama upper coastal plain.<ref>Moore, W. H. (1958). "Effects of certain prescribed fire treatments on the distribution of some herbaceous quail food plants in loblolly-shortleaf pine communities of the Alabama upper coastal plain." Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Southeastern Association of Game and Fish Commissioners 11: 349-351.</ref> This species has also been found in areas that were excluded from fire (FSU Herbarium). | G. volubilis had the greatest coverage on the January-burned plots in the loblolly-shortleaf pine communities of the Alabama upper coastal plain.<ref>Moore, W. H. (1958). "Effects of certain prescribed fire treatments on the distribution of some herbaceous quail food plants in loblolly-shortleaf pine communities of the Alabama upper coastal plain." Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Southeastern Association of Game and Fish Commissioners 11: 349-351.</ref> This species has also been found in areas that were excluded from fire (FSU Herbarium). | ||

Revision as of 14:28, 29 September 2015

| Galactia volubilis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Galactia |

| Species: | G. volubilis |

| Binomial name | |

| Galactia volubilis (L.) Britton | |

| |

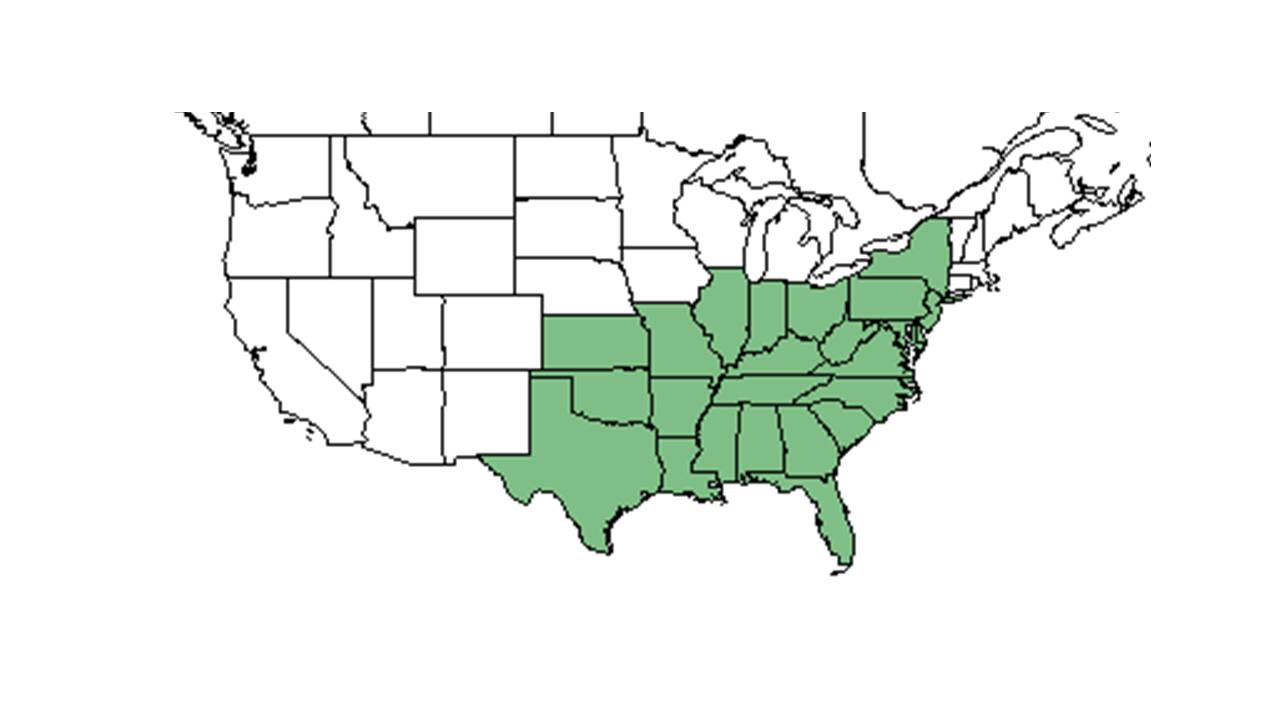

| Natural range of Galactia volubilis from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: downy milkpea

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Description

This species is a climbing vine with twining behavior (FSU Herbarium).

Distribution

“…occurring in sandy soils from New York to Florida westward to Tennessee and Texas.”[1]

Ecology

Habitat

This species is found in mixed hardwood forests, pinewoods, shrub and herb dominated communities, old fields, ravine dissected areas, dry pocosins, flatwoods, creek banks and savannahs (FSU Herbarium). It has been observed to grow in dry and moist sandy loam in open areas with full sunlight (FSU Herbarium). G. volubilis has also been seen growing in areas disturbed by humans such as bulldozed scrub sandhills, along roadsides, cleared sites, and clear cut longleaf pine-scrub habitats (FSU Herbarium).

Phenology

“A lavender-flowered prostrate perennial herb frequently climbing over bushes...It is variable species and varietal forms have been described”[1] This species has been observed to flower from May through September and November and fruiting from May to November (FSU Herbarium).

Seed dispersal

Seed bank and germination

Fire ecology

The amount of G. volubilis decreased after a spring burn, summer burn, and in the control plot[2] “Results from previous studies[3] indicate that leguminous plants and seed respond best to “hot” fires such as those in which a high proportion of the ground fuel is consumed. Laboratory tests[4] have also shown that seed from several leguminous species germinate best after scarification with moist heat at temperatures near 80 degrees C., a situation requiring a hot fire. The response of the leguminous plants and seed in this study, therefore, would probably have been greater if the pine stands had been burned with more intense fires. Nevertheless, further work will be necessary before we can make final conclusions about the value of prescribed burning to quail and other wildlife in the 2.5 million acres of pine in the South Carolina Piedmont.”[2] G. volubilis had the greatest coverage on the January-burned plots in the loblolly-shortleaf pine communities of the Alabama upper coastal plain.[5] This species has also been found in areas that were excluded from fire (FSU Herbarium).

Pollination

Use by animals

Eastern mourning dove includes G. volubilis in its diet.[1]

Diseases and parasites

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Gary R. Knight, Richard S. Mitchell, R.K. Godfrey, L. M. Baltzell, O. Lakela, J. Ferborgh, Jane Brockmann, R. W. Long, L. J. Brass, H. A. Lang, C. Jackson, A. F. Clewell, R. C. Phillips, R. Kral, M. Davis, Richard R. Clinebell II, R. L. Wilbur, W. B. Fox, R. Komarek, J.M. Kane, Chris Cooksey, Kevin Oakes, Charles S. Wallis, John B. Nelson, and D.E. Kennemore. States and Counties: Florida: Citrus, Dade, Duval, Escambia, Gulf, Franklin, Hardee, Hernando, Hillsborough, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Levy, Monroe, St. Lucie, Taylor, and Wakulla. Georgia: Grady, McIntosh, and Thomas. North Carolina: Craven and Cumberland. Oklahoma: Latimer. South Carolina: Orangeburg and Richland.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Graham, E. H. (1941). Legumes for erosion control and wildlife. Washington, USDA

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cushwa, C. T., M. Hopkins, et al. (1970). Response of legumes to prescribed burns in loblolly pine stands of the South Carolina Piedmont. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SE-140: 6.

- ↑ Cushwa, C. T., Czuhai, Eugene, Cooper, R. W., and Julian, W. H. 1969. Burning clearcut openings in Ioblolly pine to improve wildlife habitat. Ga. Forest Res. Count. Res. Pap. 61, 5 pp. Cushwa, C. T. and Redd, J. B. 1966. One prescribed burn and its effects on habitat of the Powhatan Game Management Area. Southeast. Forest Exp. %a., U. S. Forest Serv. Res. Note SE-61, 2 pp.

- ↑ Cushwa, C. T., Martin, R. E., and Miller, R. L. 1968. The effects of fire on seed germination. J. Range Manage. 21: 250-254. M a r t i n , R . E., a n d C u s h w a , C . T. 1966. Effects of heat and moisture on leguminous seed. Fifth Annu. Tall Timbers Fire Ecol. Conf. Proc. 1966: 159-175.

- ↑ Moore, W. H. (1958). "Effects of certain prescribed fire treatments on the distribution of some herbaceous quail food plants in loblolly-shortleaf pine communities of the Alabama upper coastal plain." Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Southeastern Association of Game and Fish Commissioners 11: 349-351.