Galactia volubilis

| Galactia volubilis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Walter K. Taylor, Atlas of Florida Vascular Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Galactia |

| Species: | G. volubilis |

| Binomial name | |

| Galactia volubilis (L.) Britton | |

| |

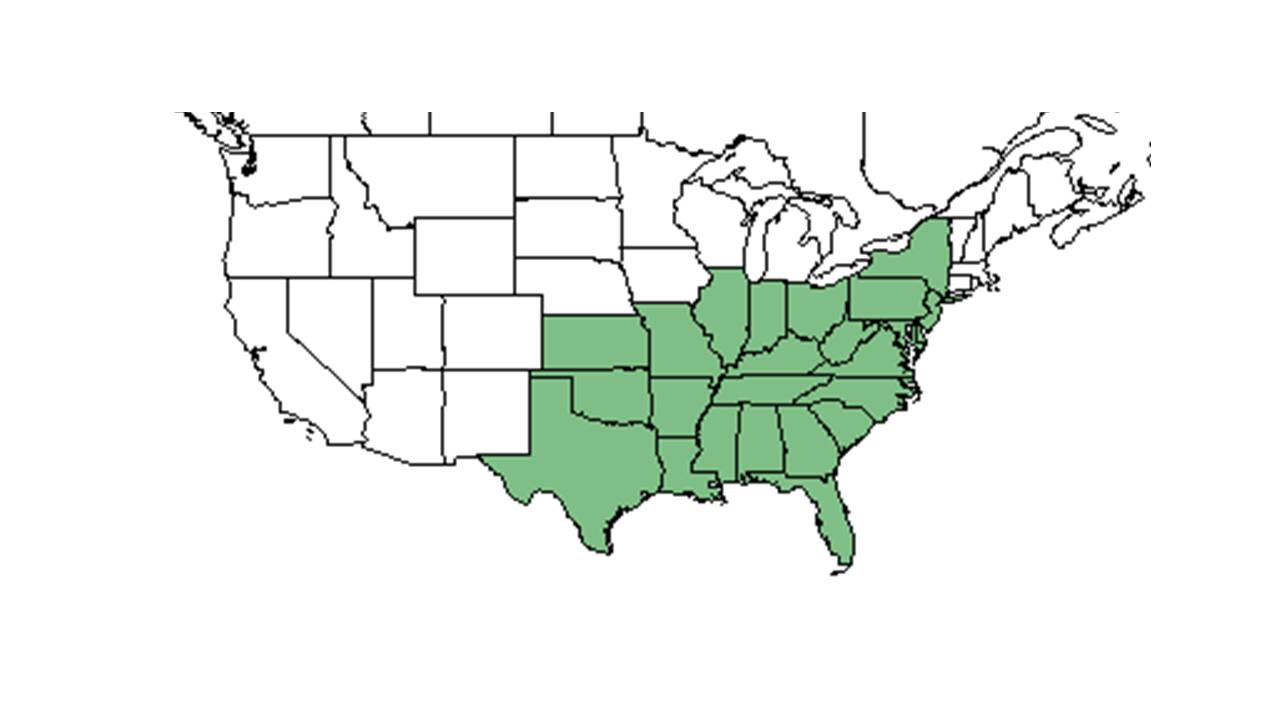

| Natural range of Galactia volubilis from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Downy milkpea

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Galactia volubilis var. volubilis Ward & Hall[1]

Variations: Galactia brachypoda Torrey & A. Gray; G. brevipes Small; G. regularis (Linnaeus) Britton[1]

Description

This species is a climbing vine with twining behavior.[2]

Generally, the genus Galactia are "trailing or twining, climbing, perennial, herbaceous or woody vines or erect, perennial herbs or rarely shrubs. Leaves 1-pinnate, usually 3-foliolate (or rarely 1-,5-7-,9-folilolate); leaflets entire, petiolulate, stipellate. Racemes axillary, pedunculate with few to numerous, papilionaceous flowers borne solitary or 2-several at a node, ech subtended by a bract and fusion of the 2 uppermost, with the laterals usually shorter than the uppermost and lowermost; petals usually red, purple, pink or white; stamens diadelphous or elsewhere occasionally monadelphous; ovary sessile or shortly stipitate. Legume oblong-linear to linear, few-many seeded, compressed, straight or slightly curbed, dehiscent with often laterally twisting valves."[3]

Specifically, for this species, G. volubilis, they are "twining, climbing, herbaceous vines with sparsely to densely, spreading pubescent stems, 1-1.5 m long. Leaves 3-foliolate, rachis 2-18 mm long; leaflets narrowly to widely oblong, oblong-ovate or elliptic, (1) 2-4 (6) cm long, glabrous, or nearly so, above and glabrate to more commonly appressed short-pubescent to spreading pilose beneath. Racemes with peduncles and rachises sparsely to densely spreading short-pubescent, 3-15 (30) cm long; flowers 1-3 at each node on spreading short-pubescent pedicles 1-4 mm long subtended by triangular bracts 0.4-1.2 mm long; bractlets triangular, 0.4-1 mm long. Calyx spreading short-pubescent, tube 2-2.5 mm long, lobes 2-3.5 mm long; petals pink to roseate, the standard 7-10 mm long. Legume 2-5.5 cm long, 4-5 mm broad, densely spreading short-pubescent." [3]

The root system of G. volubilis includes stem tubers which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[4] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 326.2 mg/g (ranking 12 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 67% (ranking 45 out of 100 species studied).[4]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Galactia volubilis has stem tubers with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 2.56 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 326.2 mg g-1.[5]

Distribution

Is distributed to sandy soils from New York to Florida westward to Tennessee and Texas. [6]

Ecology

Habitat

Generally, G. volubilis grows in sandhills and other dry forests or openings.[1] This species is found in mixed hardwood forests, pinewoods, shrub and herb dominated communities, old fields, ravine dissected areas, dry pocosins, flatwoods, creek banks and savannahs. It has been observed to grow in dry and moist sandy loam in open areas with full sunlight. G. volubilis has also been seen growing in areas disturbed by humans such as bulldozed scrub sandhills, along roadsides, cleared sites, and clear cut longleaf pine-scrub habitats.[2] It also grows in borders of woods, dry thickets, and other similar habitats.[7] In a study on early-successional communities in Mississippi, this species was found to be positively associated with damaged areas with an open canopy.[8] As well, in a study at Panola Mountain in Georgia, G. volubilis was commonly found around lake-shores.[9] Overall, it is associated with low light intervals and shadier areas.[10] Additionally, a study exploring longleaf pine patch dynamics found G. volubilis to be most strongly represented within stands of longleaf pine that are between 50-130 years of age.[11] G. volubilis is considered an indicator species of the clayhill longleaf woodlands habitat in Florida.[12]

Associated species include Desmodium ochrolecum, D. rotundifolium, Rhus aromatica, Centrosema species, Paspalum species, Fagus species, Carya tomentosa, Pinus palustris, Pinus elliottii, Quercus laurifolia, Quercus virginiana, Quercus laevis, Sabal palmetto, Magnolia ashei, Aristida stricta. Galactia regularis, Rhynchosia difformis, Setaria, Phlox, and Cuphea. Also includes Broomsage and Silver palm.[2]

Phenology

This species generally flowers from June through August, and fruits from July to October.[1] “A lavender-flowered prostrate perennial herb frequently climbing over bushes. It is variable species and varietal forms have been described.”[6] G. volubilis has been observed to flower from May through September and November with peak inflorescence in July and fruiting from May to November.[2][13]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. [14]

Fire ecology

The amount of G. volubilis decreased after a spring burn, summer burn, and in the control plot[15]; however, a study by Hodgkins found this species to respond more positively to a burn in January than a burn in August with statistical significance.[16] “Results from previous studies[17] indicate that leguminous plants and seed respond best to “hot” fires such as those in which a high proportion of the ground fuel is consumed. Laboratory tests[18] have also shown that seed from several leguminous species germinate best after scarification with moist heat at temperatures near 80 degrees C., a situation requiring a hot fire. The response of the leguminous plants and seed in this study, therefore, would probably have been greater if the pine stands had been burned with more intense fires. ”[15] G. volubilis had the greatest coverage on the plots burned in January at the loblolly-shortleaf pine communities of the Alabama upper coastal plain.[19] G. volubilis was found to be associated with a low amount of fire frequency with statistical significance.[20] This species has also been found in areas that were excluded from fire.[2]

Populations of Galactia volubilis have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[21] [22]

Pollination

Galactia volubilis has been observed to host a variety of bees such as Melissodes comptoides (family Apidae).[23]

Herbivory and toxicology

This species consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for large and small mammals, and about 5-10% of the diet for various terrestrial birds.[24] Eastern mourning dove includes G. volubilis in its diet.[6]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Galactia volubilis is listed as endangered by the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection and Energy, Office of Natural Lands Management, listed as threatened by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Natural Areas and Preserves, and listed as extirpated by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.[25] If using herbicides for management purposes, G. volubilis was found to be tolerant of the herbicide imazapyr.[26]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Gary R. Knight, Richard S. Mitchell, R.K. Godfrey, L. M. Baltzell, O. Lakela, J. Ferborgh, Jane Brockmann, R. W. Long, L. J. Brass, H. A. Lang, C. Jackson, A. F. Clewell, R. C. Phillips, R. Kral, M. Davis, Richard R. Clinebell II, R. L. Wilbur, W. B. Fox, R. Komarek, J.M. Kane, Chris Cooksey, Kevin Oakes, Charles S. Wallis, John B. Nelson, and D.E. Kennemore. States and Counties: Florida: Citrus, Dade, Duval, Escambia, Gulf, Franklin, Hardee, Hernando, Hillsborough, Jackson, Jefferson, Leon, Levy, Monroe, St. Lucie, Taylor, and Wakulla. Georgia: Grady, McIntosh, and Thomas. North Carolina: Craven and Cumberland. Oklahoma: Latimer. South Carolina: Orangeburg and Richland.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. Print.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Graham, E. H. (1941). Legumes for erosion control and wildlife. Washington, USDA

- ↑ [[1]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 13, 2019

- ↑ Brewer, S. J., et al. (2012). "Do natural disturbances or the forestry practices that follow them convert forests to early-successional communities?" Ecological Applications 22: 442-458.

- ↑ Bostick, P. E. (1971). "Vascular Plants of Panola Mountian, Georgia " Castanea 46(3): 194-209.

- ↑ Platt, W. J., et al. (2006). "Pine savanna overstorey influences on ground-cover biodiversity." Applied Vegetation Science 9: 37-50.

- ↑ Mugnani et al. (2019). “Longleaf Pine Patch Dynamics Influence Ground-Layer Vegetation in Old-Growth Pine Savanna”.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 9 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cushwa, C. T., M. Hopkins, et al. (1970). Response of legumes to prescribed burns in loblolly pine stands of the South Carolina Piedmont. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SE-140: 6.

- ↑ Hodgkins, E. J. (1958). "Effects of fire on undergrowth vegetation in upland southern pine forests." Ecology 39(1): 36-46.

- ↑ Cushwa, C. T., Czuhai, Eugene, Cooper, R. W., and Julian, W. H. 1969. Burning clearcut openings in Loblolly pine to improve wildlife habitat. Ga. Forest Res. Count. Res. Pap. 61, 5 pp. Cushwa, C. T. and Redd, J. B. 1966. One prescribed burn and its effects on habitat of the Powhatan Game Management Area. Southeast. Forest Exp. %a., U. S. Forest Serv. Res. Note SE-61, 2 pp.

- ↑ Cushwa, C. T., Martin, R. E., and Miller, R. L. 1968. The effects of fire on seed germination. J. Range Manage. 21: 250-254. M a r t i n , R . E., a n d C u s h w a , C . T. 1966. Effects of heat and moisture on leguminous seed. Fifth Annu. Tall Timbers Fire Ecol. Conf. Proc. 1966: 159-175.

- ↑ Moore, W. H. (1958). "Effects of certain prescribed fire treatments on the distribution of some herbaceous quail food plants in loblolly-shortleaf pine communities of the Alabama upper coastal plain." Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the Southeastern Association of Game and Fish Commissioners 11: 349-351.

- ↑ Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 13 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ (2000). The role of fire in nongame wildlife management and community restoration: Traditional uses and new directions, Nashville, TN, USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station.