Difference between revisions of "Lespedeza repens"

Juliec4335 (talk | contribs) |

Juliec4335 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

Vegetation composition and diversity of 13-year-old stands. Canadian Journal of Forest 23:2271-2277</ref> In Florida clayhill longleaf woodlands, ''L. repens'' was reported with a relative frequency of 93 and coverage of 0.38. Panhandle silty longleaf woodlands had frequencies of 82 and coverage of 0.27.<ref name="Carr et al 2010">Carr SC, Robertson KM, Peet RK (2010) A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75(2):153-189.</ref> ''L. repens'' responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plains communities.<ref>Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.</ref> However, it responds positively to clearcutting and chopping in South Carolina.<ref>Cushwa, C.T. and M.B. Jones. (1969). Wildlife Food Plants on Chopped Areas in Piedmont South Carolina. Note SE-119. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 4 pp.</ref> ''L. repens'' responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.<ref>Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.</ref> | Vegetation composition and diversity of 13-year-old stands. Canadian Journal of Forest 23:2271-2277</ref> In Florida clayhill longleaf woodlands, ''L. repens'' was reported with a relative frequency of 93 and coverage of 0.38. Panhandle silty longleaf woodlands had frequencies of 82 and coverage of 0.27.<ref name="Carr et al 2010">Carr SC, Robertson KM, Peet RK (2010) A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75(2):153-189.</ref> ''L. repens'' responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plains communities.<ref>Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.</ref> However, it responds positively to clearcutting and chopping in South Carolina.<ref>Cushwa, C.T. and M.B. Jones. (1969). Wildlife Food Plants on Chopped Areas in Piedmont South Carolina. Note SE-119. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 4 pp.</ref> ''L. repens'' responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.<ref>Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.</ref> | ||

| − | ''Lespedeza repens'' is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community | + | ''Lespedeza repens'' is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands and Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).<ref>Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.</ref> |

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

Revision as of 22:49, 22 July 2020

| Lespedeza repens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Southeastern Flora Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Genus: | Lespedeza |

| Species: | L. repens |

| Binomial name | |

| Lespedeza repens L | |

| |

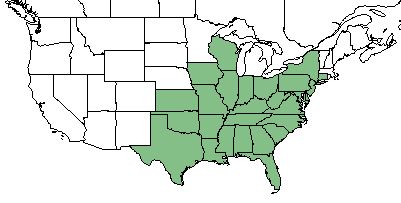

| Natural range of Lespedeza repens from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: smooth trailing lespedeza;[1] creeping lespedeza;[2] bushclover[3]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonym: Hedysarum repens[2]

Description

Lespedeza repens is a dioecious perennial forb/herb.[2] Its stems and peduncles are sparsely short-appressed-pubescent. Stems can grow to 1 m in length. Racemes typically contain 4-8 flowers that are 5-7 mm long. Leaves gradually get smaller towards the stem tips. Terminal leaflets are membranous, elliptic to obovate, glabrous, and can reach 2.5 cm in length.[4] Hybridization of L. repens and L. hirta has been reported in Missouri.[5]

Distribution

This species occurs from Connecticut and New York, westward to northern Ohio, southern Wisconsin, Missouri, and Kansas, and southward to northern peninsular Florida, panhandle Florida, and central Texas.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

L. repens is occurs in woodlands and woodland borders.[1] In a North Carolina woodland, L. repens was found with 0.8 stems m-2, a frequency of 0.188, and percent cover of 0.10.[6] In Florida clayhill longleaf woodlands, L. repens was reported with a relative frequency of 93 and coverage of 0.38. Panhandle silty longleaf woodlands had frequencies of 82 and coverage of 0.27.[7] L. repens responds negatively to agricultural-based soil disturbance in South Carolina coastal plains communities.[8] However, it responds positively to clearcutting and chopping in South Carolina.[9] L. repens responds negatively to soil disturbance by agriculture in Southwest Georgia.[10]

Lespedeza repens is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands and Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[11]

Phenology

In the southeastern and mid-Atlantic United States flowering occurs from July through September and fruiting occurs from August through November.[1]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by translocation on animal fur or feathers. [12]

Fire ecology

L. repens may require fire to maintain higher frequencies. On the Florida panhandle sandhills, its frequency was 25 in 1966. After 57 years of not burning, the frequency dropped to 4.[13]

Use by animals

L. repens composes 2-5% of the diet of some large mammals and 10-25% of some terrestrial birds.[14] During a study in central Texas, L. repens was the most preferred forage in 1996 and third preferred in 1997 by white-tailed deer. The study also showed L. repens is 16.9% crude protien and 78.4% condensed tannin.[15]

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley AS (2015) Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 12 February 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ White-tailed deer foods of the United States. The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3):314-332.

- ↑ Clewell AF (1966) Native North American species of Lespedeza (Leguminosae). Rhodora 68(775):359-405.

- ↑ Mackenzie KK (1907) A hybrid Lespedeza. Torreya 7(4):76-78.

- ↑ Clinton BD, Vose JM, Swank WT (1993) Site preparation burning to improve southern Appalachian pine-hardwood stands: Vegetation composition and diversity of 13-year-old stands. Canadian Journal of Forest 23:2271-2277

- ↑ Carr SC, Robertson KM, Peet RK (2010) A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75(2):153-189.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Cushwa, C.T. and M.B. Jones. (1969). Wildlife Food Plants on Chopped Areas in Piedmont South Carolina. Note SE-119. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 4 pp.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Clewell AF (2014) Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida. Castanea 79(3):147-167.

- ↑ Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Littlefield KA, Mueller JP, Muir JP, Lambert BD (2011) Correlation of plant condensed tannin and nitrogen concentrations to white-tailed deer browse preference in the cross timbers. The Texas Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resource 24:1-7.