Lespedeza repens

| Lespedeza repens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Southeastern Flora Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae |

| Genus: | Lespedeza |

| Species: | L. repens |

| Binomial name | |

| Lespedeza repens L | |

| |

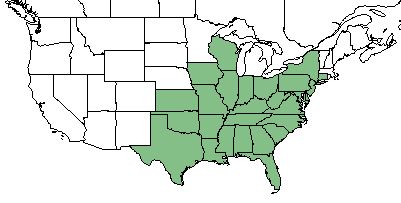

| Natural range of Lespedeza repens from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: smooth trailing lespedeza,[1] creeping lespedeza;[2] bushclover[3]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

Lespedeza repens is a dioecious perennial forb/herb.[2] Its stems and peduncles are sparsely short-appressed-pubescent. Stems can grow to 1 m in length. Racemes typically contain 4-8 flowers that are 5-7 mm long. Leaves gradually get smaller towards the stem tips. Terminal leaflets are membranous, elliptic to obovate, glabrous, and can reach 2.5 cm in length.[4] Hybridization of L. repens and L. hirta has been reported in Missouri.[5]

Distribution

This species occurs from Connecticut and New York, westward to northern Ohio, southern Wisconsin, Missouri, and Kansas, and southward to northern peninsular Florida, panhandle Florida, and central Texas.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

L. repens is found in turkey oak sand ridges, dry longleaf pine sandhills, wire grass sand ridges, clay fields, pine flatwoods, and areas with loamy sands.[6] It is also found in disturbed areas including burned longleaf pine forests, along roadsides, fallow fields, vacant lots, and burned saw palmetto-slash pine woodland.[6] Associated species: Tephrosia, Psoralea, Scleria, and Rhynchospora.[6] Lespedeza repens is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands and Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[7] L. repens is occurs in woodlands and woodland borders.[1] In a North Carolina woodland, L. repens was found with 0.8 stems m-2, a frequency of 0.188, and percent cover of 0.10.[8] In Florida clayhill longleaf woodlands, L. repens was reported with a relative frequency of 93 and coverage of 0.38. Panhandle silty longleaf woodlands had frequencies of 82 and coverage of 0.27.[9] A study exploring longleaf pine patch dynamics found L. repens to be most strongly represented within stands of longleaf pine that are between 10-130 years of age.[10]

L. repens was found to decrease its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina and southwest Georgia.[11][12] It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished pine woodlands that were disturbed by agriculture, making it a remnant woodland indicator species.[11] However, it was found to increase its occurrence and abundance in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in South Carolina. It has shown regrowth in reestablished native habitats that were disturbed by these practices.[13]

Phenology

L. repens has been observed to flower from April to October[14], with peak inflorescence in April. Fruiting has been observed from August to November.[1]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by translocation on animal fur or feathers.[15]

Fire ecology

L. repens may require fire to maintain higher frequencies. On the Florida panhandle sandhills, its frequency was 25 in 1966. After 57 years of not burning, the frequency dropped to 4.[16]

Populations of Lespedeza repens have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[17][18]

Herbivory and toxicology

L. repens has been observed to host ground-nesting bees such as Calliopsis andreniformis (family Andrenidae), sweat bees such as Nomia maneei (family Halictidae), and leafcutting bees from the Megachilidae family such as Megachile brevis, M. exilis, and M. mendica.[19] L. repens composes 2-5% of the diet of some large mammals and 10-25% of some terrestrial birds.[20] During a study in central Texas, L. repens was the most preferred forage in 1996 and third preferred in 1997 by white-tailed deer. The study also showed L. repens is 16.9% crude protien and 78.4% condensed tannin.[21]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 USDA NRCS (2016) The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 12 February 2018). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ White-tailed deer foods of the United States. The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3):314-332.

- ↑ Clewell AF (1966) Native North American species of Lespedeza (Leguminosae). Rhodora 68(775):359-405.

- ↑ Mackenzie KK (1907) A hybrid Lespedeza. Torreya 7(4):76-78.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, A. F. Clewell, Angus Gholson, R.K. Godfrey, and R. Kral. States and counties: Florida: Calhoun, Franklin, Gadsden, Jackson, Leon, Wakulla, and Washington.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Clinton BD, Vose JM, Swank WT (1993) Site preparation burning to improve southern Appalachian pine-hardwood stands: Vegetation composition and diversity of 13-year-old stands. Canadian Journal of Forest 23:2271-2277

- ↑ Carr SC, Robertson KM, Peet RK (2010) A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75(2):153-189.

- ↑ Mugnani et al. (2019). “Longleaf Pine Patch Dynamics Influence Ground-Layer Vegetation in Old-Growth Pine Savanna”.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ Kirkman, L.K., K.L. Coffey, R.J. Mitchell, and E.B. Moser. Ground Cover Recovery Patterns and Life-History Traits: Implications for Restoration Obstacles and Opportunities in a Species-Rich Savanna. (2004). Journal of Ecology 92(3):409-421.

- ↑ Cushwa, C.T. and M.B. Jones. (1969). Wildlife Food Plants on Chopped Areas in Piedmont South Carolina. Note SE-119. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southeastern Forest Experiment Station. 4 pp.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 19 MAY 2021

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Clewell AF (2014) Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida. Castanea 79(3):147-167.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Miller JH, Miller KV (1999) Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Littlefield KA, Mueller JP, Muir JP, Lambert BD (2011) Correlation of plant condensed tannin and nitrogen concentrations to white-tailed deer browse preference in the cross timbers. The Texas Journal of Agriculture and Natural Resource 24:1-7.