Difference between revisions of "Asclepias humistrata"

KatieMccoy (talk | contribs) (→Seed dispersal) |

KatieMccoy (talk | contribs) (→Seed dispersal) |

||

| Line 39: | Line 39: | ||

===Seed dispersal=== | ===Seed dispersal=== | ||

The fruit dries and splits open, releasing seeds with a white, silky pappus that allows for wind dispersal<ref name="fnps"/>. | The fruit dries and splits open, releasing seeds with a white, silky pappus that allows for wind dispersal<ref name="fnps"/>. | ||

| − | + | ===Seed bank and germination=== | |

| + | Germination is delayed until late winter or spring when seeds have after-ripened and environmental temperatures increase to match seeds germination requirements<ref name="xerces"/>. | ||

===Fire ecology===<!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology===<!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

Revision as of 18:21, 30 March 2016

Common name: Pinewoods Milkweed; Sandhill Milkweed

| Asclepias humistrata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Asclepias humistrata | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Dicots |

| Order: | Gentianales |

| Family: | Apocynaceae |

| Genus: | Asclepias |

| Species: | A. humistrata |

| Binomial name | |

| Asclepias humistrata Walter | |

| |

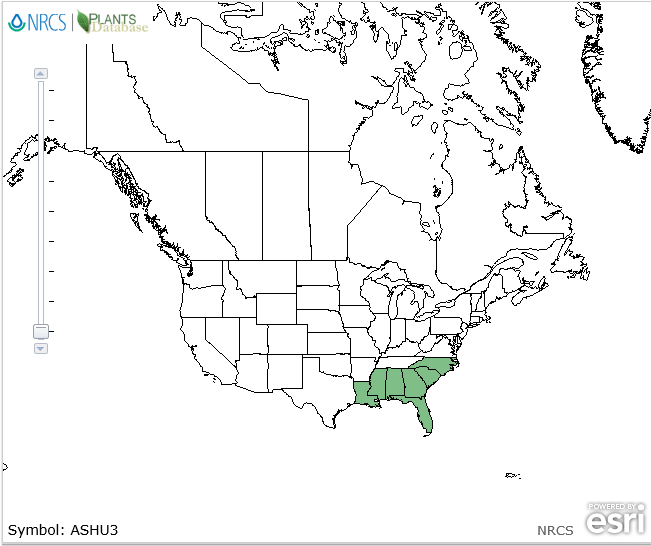

| Natural range of Asclepias humistrata from USDA NRCS [1]. | |

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Asclepias is named for Asklepio, the Greek god of medicine and healing. Humistrata is derived from the Latin word 'humis' meaning ground and 'sternere' to spread[1].

Description

In general, with the Asclepias genus, they are perennial herbs usually milky sap. The stems are erect, spreading or decumbent and usually are simple and often solitary. The leaves are opposite to subopposite, are sometimes whorled, and rarely alternate. The corolla lobes are reflexed and are rarely erect or spreading. The filaments are elaborate into five hood forming a corona around the gynosteguim. The corona horns are present in most species[2].

More specifically, for A. humistrata, the stems are glabrous, simple, stout, and rarely solitary; they spread ascendingly, and grow 2-7 dm tall. The leaves are opposite, about 5-8 pairs, ovate in shape, and 6-10 cm long, 4.5-8.5 cm wide. The leaves are widely acute to obtuse, the margins are flat, auriculate, more or less amplexicaul, subsucculent, glaucous, the veins are pink to lavender in color, and are sessile. There are 2-5 or more umbels beginning from the upper 2-5 nodes, and are 3-5 cm broad. The corolla is pale rose or lavender in color, the lobes are reflexed, and are 5-6.5 mm long. The corona is 3-5 mm in diameter. The horns are shorter than the hood. The follicles are erect and are 9-14 cm long, 1.3-1.8 cm broad. Flowers May to June; June to July.[2].

Distribution

Endemic to the southeastern U.S.: North Carolina south to Florida and west to Louisiana[1].

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain in Florida and Georgia, A. humistrata can occur in scrub oak sand ridges, longleaf pine-scrub oak ridges, pine-palmetto thickets, turkey oak scrubs, low sand dunes, and mixed pine hardwood associations. It can occur in disturbed areas such as sandy fallow fields and roadsides. Associated species include Coreopsis basalis, Hymenopappus scabiosaeus, Liatris, Panicum, Leptoloma cognatum, Q. laevis, Q. incana, Q. geminata, Aristida stricta, Vaccinium stamineum, V. myrsinites and Licania michauxii. Soil types include loamy sand and coarse sand[3].

Phenology

Flowers March through October and fruits April through October[3].

Seed dispersal

The fruit dries and splits open, releasing seeds with a white, silky pappus that allows for wind dispersal[1].

Seed bank and germination

Germination is delayed until late winter or spring when seeds have after-ripened and environmental temperatures increase to match seeds germination requirements[4].

Fire ecology

It has been observed growing in burned over, longleaf pine forests[3]. A long, deep, thick taproot aids in rapid recovery after fire[1].

Pollination

Pollination of Asclepias is unusual. Pollen is contained in sacs (pollinia) located in the slits of the flower (stigmatic slits), when a pollinator walks across the flower head, these sacs attach to the pollinator and disperses on to another plant when the pollinator lands and walks[1]. There is no specialist insect pollinator[4].

Use by animals

This species is an important host plant to the monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus) and the Queen butterfly (Danaus gilippus). Monarch larva feed upon the milkweed plants, ingesting the plant defense chemicals (cardenolids). Monarch caterpillars have evolved the ability to circumvent latex defence of milkweeds and appropriate the cardenolids. However, they can only tolerate a certain level of the cardiac glycoside chemicals, larval survival is negatively correlated with the concentration of cardiac glycosides in the leaves. Many larvae will die because they can become adhered by the latex to the leaf surface[5]. Cohen and Brower (1982) observed that more eggs are laid on larger plants, however, larval success was greatest on smaller plants. There is a positive correlation between the number of eggs on a plant and total leaf area[6].

Conservation and Management

Cultivation and restoration

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: November 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, M. Boothe, Edwin L. Bridges, Richard Carter, Jack P. Davis, Elmer, J.P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, R.D. Houk, Lisa Keppner, Gary R. Knight, Robert Kral , H. Larry, Robert L. Lazor, Karen MacClendon, Sidney McDaniel, R.A. Norris, Steve L. Orzell, C. Prichard, Grady W. Reinert, Annie Schmidt, E. Stipling, D.B. Ward, S.J. Ward, Rodie White, Mary Margaret Williams, Jean W. Wooten. States and Counties: Florida: Baker, Bay, Calhoun, Clay, Dixie, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Hamilton, Jackson, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Marion, Nassau, Okaloosa, Pasco, Polk, Santa Rosa, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, Washington. Georgia: Grady. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 848-852. Print.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 [[2]]Florida Native Plant Society. Accessed: March 30, 2016

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 848-852. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: November 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, M. Boothe, Edwin L. Bridges, Richard Carter, Jack P. Davis, Elmer, J.P. Gillespie, Robert K. Godfrey, R.D. Houk, Lisa Keppner, Gary R. Knight, Robert Kral , H. Larry, Robert L. Lazor, Karen MacClendon, Sidney McDaniel, R.A. Norris, Steve L. Orzell, C. Prichard, Grady W. Reinert, Annie Schmidt, E. Stipling, D.B. Ward, S.J. Ward, Rodie White, Mary Margaret Williams, Jean W. Wooten. States and Counties: Florida: Baker, Bay, Calhoun, Clay, Dixie, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Hamilton, Jackson, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Marion, Nassau, Okaloosa, Pasco, Polk, Santa Rosa, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, Washington. Georgia: Grady. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 [[3]]Xerces Society. Accessed: March 30, 2016

- ↑ Zalucki, M. P., L. P. Brower, et al. (2001). "Detrimental effects of latex and cardiac glycosides on survival and growth of first-instar monarch butterfly larvae Danaus plexippus feeding on the sandhill milkweed Asclepias humistrata." ECOLOGICAL ENTOMOLOGY 26(2): 212-224.

- ↑ Cohen, J. A. and L. P. Brower (1982). "Oviposition and Larval Success of Wild Monarch Butterflies (Lepidoptera: Danaidae) in Relation to Host Plant Size and Cardenolide Concentration." Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society 55(2): 343-348.