Difference between revisions of "Hypericum hypericoides"

Emmazeitler (talk | contribs) (→Seed bank and germination) |

Adam.Vansant (talk | contribs) |

||

| (15 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

Common name: St. Andrew's cross | Common name: St. Andrew's cross | ||

==Taxonomic notes== | ==Taxonomic notes== | ||

| − | Synonyms: ''Ascyrum hypericoides'' Linnaeus | + | Synonyms: ''Ascyrum hypericoides'' Linnaeus<ref name=weakley>Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.</ref> |

| − | Varieties: | + | Varieties: ''A. hypericoides'' Linnaeus ''var. hypericoides''; ''A. hypericoides'' Linnaeus ''var. oblongifolium'' (Spach) Fernald<ref name=weakley/> |

==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

| − | It is distributed from New Jersey, western Virginia, central Kentucky, southeastern Missouri, and central Oklahoma south to southern Florida and eastern Texas. It is also native to the West Indies, Mexico, and South America.<ref name= | + | It is distributed from New Jersey, western Virginia, central Kentucky, southeastern Missouri, and central Oklahoma south to southern Florida and eastern Texas. It is also native to the West Indies, Mexico, and South America.<ref name=weakley/> |

==Ecology== | ==Ecology== | ||

===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ===Habitat=== <!--Natural communities, human disturbed habitats, topography, hydrology, soils, light, fire regime requirements for removal of competition, etc.--> | ||

| − | Generally, ''H. hypericoides'' | + | Generally, ''H. hypericoides'' is found in various woodlands and dry forests.<ref name=weakley/> It occurs in wet or moist loamy soils and semi-shady to open light conditions. It can be found in annually burned longleaf pineland, wetland depressions, limestone glades, and by ponds. However, it also appears in disturbed areas including roadsides, open fields, and pine plantations.<ref name=fsu>Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Ann F. Johnson, Wilson Baker, Loran C. Anderson, Leon Neel, R. Komarek, R.A. Norris, R.F. Doren, Robert K. Godfrey, Andre F. Clewell, Kevin Oakes, Chris Cooksey, and Sidney McDaniel. States and Counties: Florida: Franklin, Jackson, Jefferson, Lee, Leon, and Wakulla. Georgia: Baker and Thomas. Texas: Orange. Other Countries: Dominican Republic.</ref> It is associated with areas that are heavily logged, herbicided for woody plants, and burned several times, as compared to unlogged areas that are selectively herbicided for hardwoods and infrequently burned.<ref>Cipollini, M. L., J. Culberson, et al. (2012). "Herbaceous plants and grasses in a mountain longleaf pine forest undergoing restoration: a survey and comparative study." Southeastern Naturalist 11: 637-668.</ref> It is considered a possible native ground-cover indicator in upland longleaf pine communities in southern Georgia.<ref name=ostertag>Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson (2007). A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, south Georgia, USA. Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, Tallahassee, Tall Timbers Research Station.</ref> |

| + | |||

| + | ''H. hypericoides'' was found to increase its presence in response to soil disturbance by heavy silviculture in North Carolina. It has shown regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine habitat that was disturbed by these practices.<ref>Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.</ref> However, it was found to become absent or decrease its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia. It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished native pinelands that were disturbed by agricultural practices.<ref name=ostertag/> in other findings ''H. hypericoides'' was observed to be an increaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances as well as in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.<ref name=Dixon>Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.</ref> | ||

Associated species include ''Pinus palutris'' and ''Pinus elliottii.''<ref name=fsu/> | Associated species include ''Pinus palutris'' and ''Pinus elliottii.''<ref name=fsu/> | ||

| Line 45: | Line 47: | ||

===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ===Phenology=== <!--Timing off flowering, fruiting, seed dispersal, and environmental triggers. Cite PanFlora website if appropriate: http://www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ --> | ||

| − | ''H. hypericoides'' generally flowers from May until August.<ref name= | + | ''H. hypericoides'' generally flowers from May until August.<ref name=weakley/> It has been observed flowering in March, April, June, July, and September, while fruiting has been observed in September.<ref name=fsu/><ref>Nelson, G. [http://www.gilnelson.com/ PanFlora]: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016</ref> |

===Seed dispersal=== | ===Seed dispersal=== | ||

| − | This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. <ref>Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.</ref> | + | This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.<ref>Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.</ref> |

===Seed bank and germination=== | ===Seed bank and germination=== | ||

| Line 54: | Line 56: | ||

===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ===Fire ecology=== <!--Fire tolerance, fire dependence, adaptive fire responses--> | ||

| − | This species has been found in | + | This species has been found in habitats that are burned annually<ref>Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.</ref> such as the Pebble Hill plantation in north Florida<ref>Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.</ref>, indicating some level of fire tolerance.<ref name="FSU Herbarium">Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: [http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu]. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Ann F. Johnson, Wilson Baker, Loran C. Anderson, Leon Neel, R. Komarek, R.A. Norris, R.F. Doren, Robert K. Godfrey, Andre F. Clewell, Kevin Oakes, Chris Cooksey, and Sidney McDaniel. States and Counties: Florida: Franklin, Jackson, Jefferson, Lee, Leon, and Wakulla. Georgia: Baker and Thomas. Texas: Orange. Other Countries: Dominican Republic.</ref> Seedlings were found in a survey at the Ocala National Forest in Florida after a fire disturbance.<ref>Carrington, M. E. (1999). "Post-Fire Seedling Establishment in Florida Sand Pine Scrub." Journal of Vegetation Science 10(3): 403-412.</ref> It benefits most from a low fire return interval.<ref>Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.</ref> As well, it is found in higher frequency in burned-bluestem plots rather than burned-wiregrass plots in northwest Florida.<ref>Rodgers, H. L. and L. Provencher (1999). "Analysis of Longleaf Pine Sandhill Vegetation in Northwest Florida." Castanea 64(2): 138-162.</ref> |

| + | |||

<!--===Pollination===--> | <!--===Pollination===--> | ||

| − | + | ===Herbivory and toxicology===<!--Herbivory, granivory, insect hosting, etc.--> | |

| − | === | + | ''Hypericum hypericoides'' consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet of various large mammals and terrestrials birds.<ref>Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.</ref> It is known to be eaten by white-tailed deer mostly during the winter.<ref>Atwood, E. L. (1941). "White-tailed deer foods of the United States." The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3): 314-332.</ref><ref>Gee, K. L., et al. (1994). White-tailed deer: their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.</ref> |

| − | |||

===Diseases and parasites=== | ===Diseases and parasites=== | ||

It is a host plant for false spider mites, including ''Brevipalpus californicus'', ''B. obovatus'', and ''B. phoenicis''.<ref>Childers, C. C., et al. (2003). "Host plants of Brevipalpus californicus, B. obovatus, and B. phoenicis (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) and their potential involvement in the spread of viral diseases vectored by these mites." Experimental & Applied Acarology 30: 29-105.</ref> | It is a host plant for false spider mites, including ''Brevipalpus californicus'', ''B. obovatus'', and ''B. phoenicis''.<ref>Childers, C. C., et al. (2003). "Host plants of Brevipalpus californicus, B. obovatus, and B. phoenicis (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) and their potential involvement in the spread of viral diseases vectored by these mites." Experimental & Applied Acarology 30: 29-105.</ref> | ||

| − | ==Conservation and | + | ==Conservation, cultivation, and restoration== |

On the state level, ''Hypericum hypericoides'' is considered vulnerable in the state of Delaware.<ref>[[http://explorer.natureserve.org]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 24, 2019</ref> | On the state level, ''Hypericum hypericoides'' is considered vulnerable in the state of Delaware.<ref>[[http://explorer.natureserve.org]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 24, 2019</ref> | ||

| − | == | + | ==Cultural use== |

==Photo Gallery== | ==Photo Gallery== | ||

<gallery widths=180px> | <gallery widths=180px> | ||

Latest revision as of 13:48, 2 August 2024

| Hypericum hypericoides | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Theales |

| Family: | Clusiaceae ⁄ Guttiferae |

| Genus: | Hypericum |

| Species: | H. hypericoides |

| Binomial name | |

| Hypericum hypericoides (L.) Crantz | |

| |

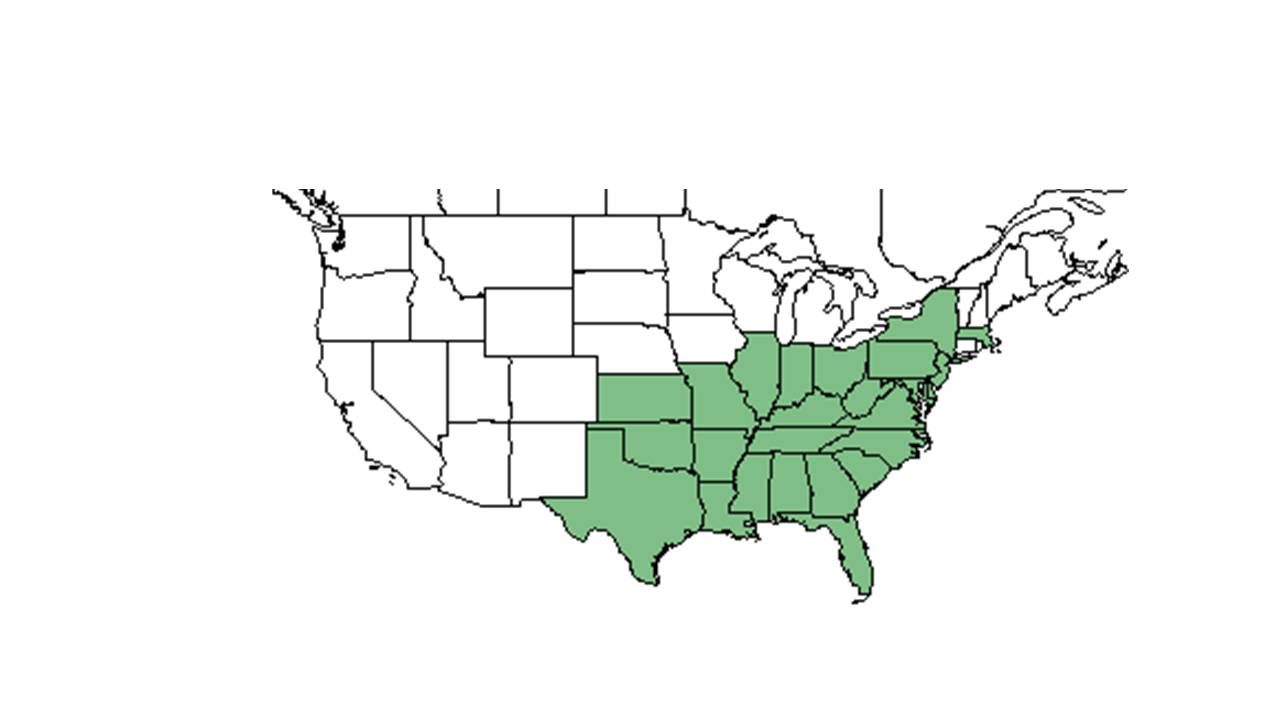

| Natural range of Hypericum hypericoides from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: St. Andrew's cross

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Ascyrum hypericoides Linnaeus[1]

Varieties: A. hypericoides Linnaeus var. hypericoides; A. hypericoides Linnaeus var. oblongifolium (Spach) Fernald[1]

Description

Hypericum hypericoides is a perennial shrub species.

“Usually glabrous herbs or shrubs. Leaves usually punctate, simple, opposite, entire, usually sessile or subsessile, exstipulate. Inflorescence basically cymose; flowers perfect, regular, bracteates, subsessile or short-pedicellate, sepals 2, 4, or 5, persistent; petals 4 or 5, usually marcescent, yellow or pink; stamens 5-numerous, separate or connate basally forming 3-5 clusters or fascicles, filaments usually persistent; carpels 2-5, stigmas and styles separate or fused, ovary superior, 1-locular or partly or wholly 2-5 locular, placentation axile or parietal. Capsules basically ovoid, longitudinally dehiscent, styles usually persistent; seeds numerous, lustrous, areolate, cylindric, or oblong. In general, our species form a polymorphic complex with many intergrading taxa.” [2]

"Shrub 3-10 dm tall with erect or ascending, wing-angled. Leaves elliptic, linear, or oblanceolate, 8-26 mm long, 1-7 mm wide, acute or obtuse, base cuneate, notched. Flowers solitary, axillary, or ins mall cymules; bracts paired, at base of sepals; pedicels ascending, 1-5 mm long. Outer sepals 2, ovate, or widely elliptic, 5-12 mm long, 3.5-7 mm wide, acute, base frequently subcordate, inner sepals usually obsolete; petal 4, 6-10 mm long; styles 2, partly fuse, 0.5-1 mm long, ovary 1-locular. Capsules ovoid, 4-9 mm long, 2.5-4 mm long, 2.5-4 mm broad; seeds black, ca.1 mm long."[2]

Distribution

It is distributed from New Jersey, western Virginia, central Kentucky, southeastern Missouri, and central Oklahoma south to southern Florida and eastern Texas. It is also native to the West Indies, Mexico, and South America.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Generally, H. hypericoides is found in various woodlands and dry forests.[1] It occurs in wet or moist loamy soils and semi-shady to open light conditions. It can be found in annually burned longleaf pineland, wetland depressions, limestone glades, and by ponds. However, it also appears in disturbed areas including roadsides, open fields, and pine plantations.[3] It is associated with areas that are heavily logged, herbicided for woody plants, and burned several times, as compared to unlogged areas that are selectively herbicided for hardwoods and infrequently burned.[4] It is considered a possible native ground-cover indicator in upland longleaf pine communities in southern Georgia.[5]

H. hypericoides was found to increase its presence in response to soil disturbance by heavy silviculture in North Carolina. It has shown regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine habitat that was disturbed by these practices.[6] However, it was found to become absent or decrease its occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia. It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished native pinelands that were disturbed by agricultural practices.[5] in other findings H. hypericoides was observed to be an increaser in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances as well as in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[7]

Associated species include Pinus palutris and Pinus elliottii.[3]

Hypericum hypericoides is frequent and abundant in the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands and Calcareous Savannas community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[8]

Phenology

H. hypericoides generally flowers from May until August.[1] It has been observed flowering in March, April, June, July, and September, while fruiting has been observed in September.[3][9]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[10]

Seed bank and germination

It was found as a prevalent member of the seed bank at a loblolly pine plantation restoration site in southwest Georgia.[11] As well, it was found in the seed bank of early successional 2- and 5-year old field sites as well as a 112-year-old field site.[12]

Fire ecology

This species has been found in habitats that are burned annually[13] such as the Pebble Hill plantation in north Florida[14], indicating some level of fire tolerance.[15] Seedlings were found in a survey at the Ocala National Forest in Florida after a fire disturbance.[16] It benefits most from a low fire return interval.[17] As well, it is found in higher frequency in burned-bluestem plots rather than burned-wiregrass plots in northwest Florida.[18]

Herbivory and toxicology

Hypericum hypericoides consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet of various large mammals and terrestrials birds.[19] It is known to be eaten by white-tailed deer mostly during the winter.[20][21]

Diseases and parasites

It is a host plant for false spider mites, including Brevipalpus californicus, B. obovatus, and B. phoenicis.[22]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

On the state level, Hypericum hypericoides is considered vulnerable in the state of Delaware.[23]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 709-713. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Ann F. Johnson, Wilson Baker, Loran C. Anderson, Leon Neel, R. Komarek, R.A. Norris, R.F. Doren, Robert K. Godfrey, Andre F. Clewell, Kevin Oakes, Chris Cooksey, and Sidney McDaniel. States and Counties: Florida: Franklin, Jackson, Jefferson, Lee, Leon, and Wakulla. Georgia: Baker and Thomas. Texas: Orange. Other Countries: Dominican Republic.

- ↑ Cipollini, M. L., J. Culberson, et al. (2012). "Herbaceous plants and grasses in a mountain longleaf pine forest undergoing restoration: a survey and comparative study." Southeastern Naturalist 11: 637-668.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson (2007). A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, south Georgia, USA. Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems, Tallahassee, Tall Timbers Research Station.

- ↑ Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Andreu, M. G., et al. (2009). "Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in Southwest Georgia?" Restoration Ecology 17: 586-596.

- ↑ Oosting, H. J. and M. E. Humphreys (1940). "Buried viable seeds in a successional series of old field and forest soils." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 67(4): 253-273.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Ann F. Johnson, Wilson Baker, Loran C. Anderson, Leon Neel, R. Komarek, R.A. Norris, R.F. Doren, Robert K. Godfrey, Andre F. Clewell, Kevin Oakes, Chris Cooksey, and Sidney McDaniel. States and Counties: Florida: Franklin, Jackson, Jefferson, Lee, Leon, and Wakulla. Georgia: Baker and Thomas. Texas: Orange. Other Countries: Dominican Republic.

- ↑ Carrington, M. E. (1999). "Post-Fire Seedling Establishment in Florida Sand Pine Scrub." Journal of Vegetation Science 10(3): 403-412.

- ↑ Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.

- ↑ Rodgers, H. L. and L. Provencher (1999). "Analysis of Longleaf Pine Sandhill Vegetation in Northwest Florida." Castanea 64(2): 138-162.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Atwood, E. L. (1941). "White-tailed deer foods of the United States." The Journal of Wildlife Management 5(3): 314-332.

- ↑ Gee, K. L., et al. (1994). White-tailed deer: their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.

- ↑ Childers, C. C., et al. (2003). "Host plants of Brevipalpus californicus, B. obovatus, and B. phoenicis (Acari: Tenuipalpidae) and their potential involvement in the spread of viral diseases vectored by these mites." Experimental & Applied Acarology 30: 29-105.

- ↑ [[1]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 24, 2019