Difference between revisions of "Chamaecrista fasciculata"

ParkerRoth (talk | contribs) |

ParkerRoth (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

''Chameacrista fasciculata'' does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its taproot.<ref name="Diaz"> Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.</ref> Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 76.2 mg/g (ranking 59 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 44% (ranking 35 out of 100 species studied).<ref name="Diaz"/> | ''Chameacrista fasciculata'' does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its taproot.<ref name="Diaz"> Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.</ref> Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 76.2 mg/g (ranking 59 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 44% (ranking 35 out of 100 species studied).<ref name="Diaz"/> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

Revision as of 12:31, 3 July 2024

| Chamaecrista fasciculata | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Michelle M. Smith | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Fabales |

| Family: | Fabaceae ⁄ Leguminosae |

| Genus: | Chamaecrista |

| Species: | C. fasciculata |

| Binomial name | |

| Chamaecrista fasciculata (Michx.) Greene | |

| |

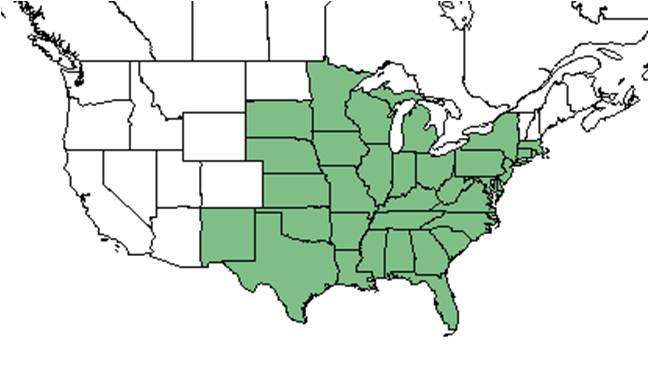

| Natural range of Chamaecrista fasciculata from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Partridge Pea, common partridge-pea, tidal-marsh partridge pea

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Chamaecrista puberula Greene; Cassia fasciculata var. brachiata (Pollard) Pullen ex Isely; Chamaecrista brachiata Pollard; Cassia fasciculata var. macrosperma Fernald[1]

Varieties: Chamaecrista fasciculata (Michaux) Greene var. 1; Chamaecrista fasciculata (Michaux) Greene var. brachiata (Pollard) Isely; Chamaecrista fasciculata (Michaux) Greene var. fasciculata; Chamaecrista fasciculata (Michaux) Greene var. macrosperma (Fernald) C.F. Reed; Chamaecrista littoralis Pollard; Chamaecrista mississippiensis (Pollard) Pollard ex Heller; Cassia fasciculata var. littoralis (Pollard) J.F. Macbride; Cassia fasciculata var. robusta (Pollard) J.F. Macbride; Chamaecrista robusta Pollard[1]

Description

Chameacrista fasciculata is an annual herb, growing 1.5-6 dm tall from the taproot. The stems and branches are glabrous to more commonly densely puberulent with incurved trichomes and occasionally also with villous trichomes to 2 mm long. The leaves are sensitive with a sessile, depressed, saucer-shaped gland, 0.5-1.5 mm in diam. near the middle of the petiole. Leaflets 12-36, linear-oblong, 1-2.5 cm long, 2-6 mm wide, inequilateral; stipules persistent, striate. Inflorescence are 1-6 flowered axillary fascicle. Pedicels grow up to 1-2 cm long. Sepals are lanceolate in shape, growing 9-12 mm long, and are acute. Petals are bright yellow in color, almost equal, growing 1-2 cm long; stamens 10, unequal, growing 10-13 mm long. The legume are elastically dehiscent, growing 3-7 cm long, and 5-7 mm broad, and are glabrate or appressed-puberulent to villous.[2]

Chameacrista fasciculata does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its taproot.[3] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 76.2 mg/g (ranking 59 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 44% (ranking 35 out of 100 species studied).[3]

Distribution

C. fasciculata is native to the eastern United States, excluding Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine, west to New Mexico, South Dakota, and Minnesota.[4]

Ecology

Like other species in the Fabaceae family, C. fasciculata is a nitrogen-fixing plant that depends on microorganisms to help produce nitrogen compounds necessary for the plant's survival. This is conducted through a symbiosis of microorganisms inhabiting root nodules of the plant to give the plant direct access and the microorganisms a safe habitat.[5]

Habitat

C. fasciculata is a facultative upland species[4] and can be found in sandy savannas of the Gulf Coastal Plain, and bluffs, prairies, river bottoms and banks, and upland woods of the Great Plains region. Generally, this species prefers well-drained and moderately lime souls such as sandy to sandy loam soils, but the wide range of soils include slightly acidic to moderately alkaline soils.[6][7] C. fasciculata is also a common colonizer of disturbed areas[6] can be found growing on recently abandoned gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) mounds,[8], dry sand, roadsides and other disturbed areas, sand ridges, sand dunes, upland old fields, scrub clearings, pine flatwoods, sandhills, wooded ravines, salt marshes, prairies, and edges of crop fields and wooded areas.[9]

C. fasciculata showed variable changes in frequency and density in response to soil disturbance by roller chopping in Northwest Florida sandhills. In reestablished native sandhill habitat, it has shown mixed regrowth response.[10] It increased its frequency and biomass in response to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests. It has shown additional regrowth in reestablished flatwoods that were disturbed by clearcutting and chopping.[11]

Associated species: Pinus palustris, Pinus elliottii, Pinus clausa, Quercus laevis, Quercus geminata, Quercus laurifolia, Quercus margaretta, Monarda punctata, Vaccinium arboreum, Cyrilla racemiflora, Serenoa repens, Chamaecrista sp., Diodia sp., Polgala sp., Aristida sp., Elymus sp., Scleria oligantha, Lygodium japonicum, and Chasmanthium sessiflorum.[9]

Phenology

C. fasciculata has been observed flowering between April and September with peak inflorescence in June and August.[12] Another source also observed C. fasciculata to flower in October, and fruit in February and April through October.[9]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates. [13]

Seed bank and germination

For propagation, seeds can be cold moist stratified for 56 days to improve germination success. Optimum soil temperature for germination is between 20 and 30 degrees Celsius. With this regiment, about 70% of seeds will germinate between 7 and 25 days.[6]

Fire ecology

Fire helps proliferate this species.[6] Winter burns, rather than spring or summer burns, significantly increase C. fasciculata in frequency as well as overall biomass of the species.[14]

Pollination

The following Hymenoptera families and species were observed visiting flowers of Chamaecrista fasciculata at Archbold Biological Station: Apis mellifera, Bombus impatiens (family Apidae), Stenodynerus histrionalis rufustus (family Vespidae), members of the family Halictidae such as Augochlora pura, Augochloropsis metallica, A. sumptuosa, Lasioglossum coreopsis, and L. placidensis, as well as members of the family Megachilidae such as Coelioxys sayi, Megachile mendica, and M. texana. [15] Other Hymenoptera observed pollinating C. fasciculata include Dialictus coreopsis, D. miniatulus, D. placidensis, Megachile brevis pseudobrevis, and Xylocopa micans.[16] Fly species in the families Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) were collected from the plant and are possible pollinators.[17] Additionally, C. fasciculata was observed to host ground-nesting bees such as Pseudopanurgus albitarsis (family Andrenidae), bees from the family Apidae such as Bombus griseocollis, B. impatiens, B. pensylvanicus, and Melissodes bimaculatus, as well as sweat bees from the family Halictidae such as Augochloropsis metallica, Lasioglossum anomalum, L. hitchensi, L illinoense, and Nomia nortoni.[18] C. fasciculata also hosts aphids such as Aphis sp. (family Aphididae), leafhoppers from the family Cicadellidae such as Agallia sp., Empoasca sp. and Graminella nigrifrons, and spittle bugs such as Clastoptera sp. (family Clastopteridae), true bugs such as Phlegyas sp. (family Lygaeidae) and Paromius longulus (family Rhyparochromidae), treehoppers such as Spissistilus festinus (family Membracidae), plant bugs from the family Miridae such as Lygus lineolaris, Pseudatomoscelis seriatus and Spanagonicus albofasciatus.[19]

Herbivory and toxicology

C. fasciculata has raised glands on its petioles that excrete a nectar that attracts predatory ants, with the presumed adaptive benefit of encouraging ants to prey on herbivores.[20] The glands have also been observed to attract bees and wasps, presumably with the same benefit to the plant.[21] As a whole, it is approximately 5-10% of the diet for large mammals, and 10-25% of the diet for terrestrial birds where it is found.[22] It is a major food item for the northern bobwhite quail and other quails due to its persistence through the winter and early spring. Partridge pea is also eaten by ring-necked pheasant, greater and lesser prairie-chicken, grassland birds, mallard, field mice, and deer; it can be poisonous for livestock and is considered potentially dangerous for cattle. Upland game birds and small non-game birds, small mammals, and waterfowl utilize the litter and plant stocks of the species for cover. As well, the common sulfur butterfly (Colias philodice) lays eggs on the leaves so that the larvae use them as their first food source.[6] It is also a larval host for other members of Lepidoptera, including the cloudless giant sulpher (Phoebis sennae), the orange sulphur (Colias eurytheme), and the sleepy orange (Abaeis nicippe).[5]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

For management, stands that are already established are recommended to be disked lightly in springtime to show mineral soil that the seeds can germinate on. This species can decrease in frequency if there is not regular maintenance, so light disking is necessary to remove old sod, small brush, and other weeds. Fire is also a great management tool to help proliferate this species; for best results, prescribed fire should be conducted in the winter. Mowing can also help control weeds through mowing over the top of C. fasciculata individuals.[6] To control erosion, C. fasciculata can be planted along road banks or stream banks for restoration as well as improving soil fertility. This is due to it being able to rapidly establish, fix nitrogen, to reseed, and decrease in frequency as other species start dominating the site. It is commonly included in seed mix with other grasses and forbs that are planted along roadsides to prevent establishment of weeds. Cultivars of C. fasciculata include 'Comanche' from the Knox City Plant Materials Center in Texas and 'Riley' from the Manhattan Plant Materials Center in Kansas.[6]

Cultural use

Historically, the Cherokee Native American tribe used the species as a medicinal drug to keep ball players from tiring as well as for spells of fainting; the Seminole tribe used C. fasciculata medicinally as a drug for nausea, and used the plant as a bed for ripening persimmons.[6]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 577-8. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 4 April 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: April 4, 2019

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 Houck, M. J. and J. M. Row. (2006). Plant Guide: Partridge Pea Chamaecrista fasciculata. N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Alexandria, LA.

- ↑ USDA NRCS Plant Materials Program and J. M. Row. (2006). Plant Fact Sheet: Showy Partridge Pea Chamaecrista fasciculata.N.R.C.S. United States Department of Agriculture. Manhattan, KS.

- ↑ Kaczor, S. A. and D. C. Hartnett (1990). "Gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) effects on soils and vegetation in a Florida sandhill." American Midland Naturalist 123: 100-111.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: March 2019. Collectors: M. A., Preston Adams, Loran C. Anderson, C. F. Baker, Fred A. Barkley, Tom Barnes, K. E. Blum, K. A. Bradley, L. J. Brass, Michael B. Brooks, Charles T Bryson, D. Burch, - Chrysler, Andre F. Clewell, D. S. Correll, V. L. Cory, G. Crosby, Mr. H. A Davis, Mrs. H. A. Davis, Delzie Demaree, F. S. Earle, Donna Marie Eggers, Joseph Ewan, S. J. Ewer, William B. Fox, Angus Gholson, G. Gil, L. M. Gil, J. P. Gillespie, William T. Gillis, Robert K. Godfrey, H. E. Grelen, Bruce Hansen, JoAnn Hansen, Randy Haynes, Norlan C. Henderson, Brenda Herring, Don Herring, R. D. Houk, C. Jackson, S. B. Jones, Samuel B. Jones, Jr., Nancy E. Jordan, - Keenan, Annette Kessler, Gary R. Knight, R. Komarek, - Kral, Robert Kral, O. Lakela, Robert L. Lazor, S. W. Leonard, S. J. Lombardo, C. L. Lundell, Karen MacClendon, Travis MacClendon, Sidney McDaniel, Geo M. Merrill, Richard S. Mitchell, Brunelle Moon, John B. Nelson, R. A. Norris, Jackie Patman, Gwynn W. Ramsey, James D. Ray, Jr., P. L. Redfearn, P. L. Redfearn, Jr., H. R. Reed, L. L. Reese, W. D. Reese, Grady W. Reinert, H. F L. Rock, Reginald Rose-Innes, Robert Runyon, J. C. Schaffner, P. O. Schallert, A. B. Seymour, Lloyd H. Shinners, B. Shrinuk, Cecil R Slaughter, R. R. Smith, Edward S. Steele, Donald E. Stone, H. Larry E. Stripling, John W. Thieret, B. L. Turner, E. Tyson, B. M. Waddle, G. W. Waldorf, D. B. Ward, R. L. Wilbur, and – Windler. States and Counties: Florida: Alachua, Bay, Brevard, Calhoun, Collier, Columbia, Dade, Dixie, Flagler, Franklin, Gadsden, Hernando, Highlands, Hillsborough, Holmes, Indian River, Jackson, Lafayette, Lake, Lee, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Monroe, Okaloosa, Osceola, Palm Beach, Polk, Santa Rosa, Sarasota, Seminole, St Johns, St Lucie, Suwannee, Taylor, Volusia, Wakulla, Walton, and Washington. Georgia: Grady, Lanier, McIntosh, and Thomas. Alabama: Baldwin, Cleburne, Dale, Lee, and Russell. Arkansas: Ashley, Bradley, Clark, Conway, Garland, Lee, Logan, Prairie, Pulaski, and Yell. Dist of Columbia. Illinois: Jasper. Indiana: Cass. Iowa: Boone and Harrison. Louisiana: Lafayette, Rapides, and St Mary. Maryland: Baltimore. Mississippi: Forrest, Harrison, Howell, Humphreys, Jackson, Lamar, Lawrence, Leake, Leflore, Pearl River, Pocahontas, Scott, Tishomingo, and Union. Missouri: Benton, Buchanan, Harrison, Lafayette, Nodaway, St Francois, and Wayne. New Jersey: Burlington and Cape May. North Carolina: Bladen, Columbus, Currituck, Dare, Davidson, Graham, Granville, Hyde, Jackson, Rockingham, Scotland, Surry, and Swain. South Carolina: Charleston, Cherokee, Colleton, and Fairfield. Tennessee: Anderson, Montgomery, Sumner, and Williamson. Texas: Anderson, Aransas, Callahan, Cameron, Cooke, Dallas, Freestone, Hemphill, Nueces, Parker, Robertson, and Van Zandt. Virginia: Greensville, Prince Edward, and Queen Annes.

- ↑ Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 7 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).

- ↑ Tooker, J. F., et al. (2006). "Floral host plants of Syrphidae and Tachinidae (Diptera) of central Illinois." Annals of the Entomological Society of America 99(1): 96-112.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [2]

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [3]

- ↑ Boecklen, W.J. 1984. The role of extrafloral nectaries in the herbivore defence of Cassia fasciculata. Ecological Entomology 9:243-249.

- ↑ David McElveen and Kevin Robertson observation on Tall Timbers Research Station, Tallahassee, Florida, July 17 and 20, 2018.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.