Toxicodendron radicans

| Toxicodendron radicans | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Paul Wray, Iowa State University, Bugwood.org hosted at Forestryimages.org | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Sapindales |

| Family: | Anacardiaceae |

| Genus: | Toxicodendron |

| Species: | T. radicans |

| Binomial name | |

| Toxicodendron radicans (L.) Kuntze | |

| |

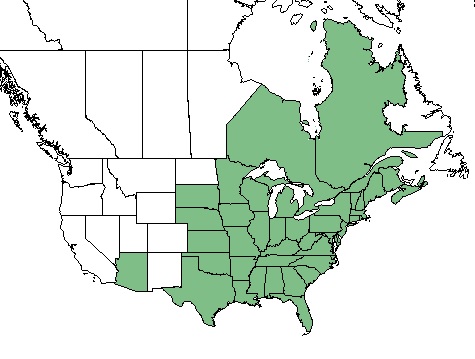

| Natural range of Toxicodendron radicans from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common Name(s): Midwestern poison ivy[1], eastern poison ivy[1][2]

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Varieties: T. radicans var. vulgaris (Michaux) A.P. de Candolle forma negundo (Greene) Fernald; T. radicans var. pubens; Toxicodendron radicans (Linnaeus) Kuntze var. negundo (Greene) Reveal.[3]

Description

Toxicodendron radicans is a dioecious perennial that grows in the form of a forb/herb, shrub, subshrub, or vine.[2] Leaves are deciduous, alternate, trifoliate, ovate with dentate margins and can change to a deep orange or red color in the fall. It requires partial to full shade. All parts of this plant are considered poisonous. Oils on the plant contain urushiol, a severe skin irritant, which can cause severe skin redness, itching, swelling and blistering following direct or indirect contact.[4] This toxicity is expected to increase as atmospheric CO2 levels increase.[5]

Distribution

It can be found from Texas north to South Dakota and Minnesota and in all of the states eastward. It has also been reported in southern Arizona and the Ontario and Quebec provinces of Canada.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

T. radicans has been found in trees occupying wooded river floodplains, cypress heads, shrub thickets, swamps, oak-sweetgum-elm forests, natural levees, and pine woodlands.[6] It is also found in disturbed areas like along roadsides.[6] Associated species: Quercus fusiformis, Q. buckleyi, Quercus candicans, Quercus castanea, Quercus crassipes, and Celtis laevigata.[7]

Additionally, T. radicans is found throughout a wide range of habitats including mesic forests, rock outcrops, open areas, disturbed areas, xeric limestone sites, swamp forests, brackish marshes, bottomlands, maritime forests.[1] In a Mississippi study, T. radicans composed 7% of the understory biomass in a pine/hardwood habitat.[8] In New Jersey old field successional habitat, T. radicans's relative abundance was one of two dominant species after 14 years of succession.[9]

It increased its presence in response to soil disturbance by heavy silvilculture in North Carolina. It has shown regrowth in reestablished longleaf sites that were disturbed by these practices.[10] T. radicans decreased its relative cover or was unaffected in response to soil disturbance by improvement logging in Mississippi.[11] It does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods forests.[12]

Tocicodendron radicans is frequent and abundant in the Calcareous Savannas community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[13]

Phenology

T. radicans has been observed flowering March to May with fruits appearing in August through October.[1][14] Flowers can contain colors of white, green and/or brown. Fruits are amber in color and 0.25 in (6.4 mm) in diameter.[4]

Fire ecology

Selective herbicides and a three year fire frequency over a period of 10 years did not significantly impact the biomass of T. radicans,[8] and populations have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[15][16]

Pollination

In Iowa, T. radicans was observed being pollenated by 37 different floral associates consisting of coleopterans (beetles), dipterans (flies), hemipterans (true bugs), hymenopterans (ants, bees, wasps), and lepidopterans (butterflies). More specifically, this species has been observed to host insects from the Cicadellidae family such as Eratoneura acantha, E. ardens, E. parva, Erythroneura tricincta, E. beameri, and Hymetta balteata, members of the insect family Flatidae such as Metcalfa pruinosa and Ormenoides venusta, and pollinators such as Slaterocoris stygicus (family Miridae).[17]

Herbivory and toxicology

This diverse assemblage may partially explain its success across varied habitats.[18] T. radicans attracts butterflies and is highly resistant to deer herbivory.[4] It comprises 10-25% of the diet of large mammals and 5-10% for small mammals and terrestrial birds.[2]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

The resin of Toxicodendron radicans contains a harmful skin irritant called urushiol[19] that should be avoided by all as the degree to which the irritation occurs varies between the individuals exposed.[20][21] All parts of this species may contain this irritant.[22] Symptoms of exposure generally include a rash, swelling, and blisters and may present immediately or be delayed for up to a few days.[23] Humans use the urushiol compounds of T. radicans to test the efficacy of skin protectant against chemical warfare agents.[24]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Weakley A. S.(2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 20 December 2017). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draf of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Plant database: Toxicodendron radicans. (20 December 2017).Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. URL: https://www.wildflower.org/plants/result.php?id_plant=TORA2

- ↑ Mohan J.E., Ziska L. H., Schlesinger W. H., Thomas R. B., Sicher R. C., George K., and Clark J. S. (2006). Biomass and toxicity responses of poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) to elevated atmospheric CO2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America 103(24):9086-9089.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Florida State University Herbarium Database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Kathy Craddock Burks, Mark A Garland, Robert K. Godfrey, Bruce Hansen, A. Mellon, Sidney McDaniel, G. Robinson, and Richard P. Wunderlin. States and counties: Florida: Calhoun, Franklin, Leon, Pasco, and Taylor.

- ↑ Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Philecology Herbarium accessed using Southeastern Regional Network of Expertise and Collections (SERNEC) data portal. URL: http://sernecportal.org/portal/collections/index.php Last accessed: June 2021. Collectors: F. J. Santana M. and Rebecca K. Swadek. States/Countries and Counties/Parishes: Texas: Parker. Mexico: Jalisco.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Iglay R. B., Leopold B. D., Miller D. A., and Burger, Jr. L. W. (2010). Effect of plant community composition on plant response to fire and herbicide treatments. Forest Ecology and Management 260:543-548.

- ↑ Myster R. W. and Pickett S. T. A. (1990). Initial conditions, history and successional pathways in ten contrasting old fields. American Midland Naturalist 124(2):231-238.

- ↑ Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ McComb, W.C. and R.E. Noble. (1982). Response of Understory Vegetation to Improvement Cutting and Physiographic Site in Two Mid-South Forest Stands. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society 47(1):60-77.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 20 DEC 2017

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Senchina D. S. and Summerville K. S. (2007). Great diversity of insect floral associates may partially explain ecological success of poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans subsp. negundo [Greene] Gillis, Anacardiaceae). The Great Lakes Entomologist 40(3-4):120-128.

- ↑ Mueschner, W.C. 1957. Poisonous Plants of the United States. The Macmillan Company, New York.

- ↑ Mueschner, W.C. 1957. Poisonous Plants of the United States. The Macmillan Company, New York.

- ↑ Burrows, G.E., Tyrl, R.J. 2001. Toxic Plants of North America. Iowa State Press.

- ↑ Hardin, J.W. 1961. Poisonous Plants of North Carolina. North Carolina State College, Raleigh, North Carolina.

- ↑ Hardin, J.W., Arena, J.M. 1969. Human Poisoning from Native and Cultivated Plants. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina.

- ↑ Liu D. K., Wannemacher R. W., Snider T. H., and Hayes T. L. (1999). Efficacy of the topical skin protectant in advanced development. Journal of Applied Toxicology 19(supp 1):S41-S45.