Prunus serotina

Common name: wild black cherry, plateau wild black cherry, escarpment black cherry, eastern wild black cherry, bird cherry[1]

| Prunus serotina | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by John Gwaltney hosted at Southeastern Flora.com | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Rosaceae |

| Genus: | Prunus |

| Species: | P. serotina |

| Binomial name | |

| Prunus serotina Ehrh. | |

| |

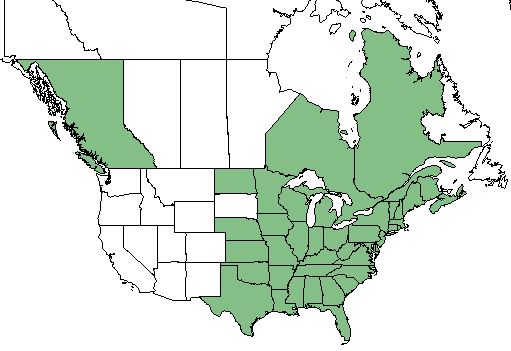

| Natural range of Prunus serotina from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Prunus serotina ssp. serotina[1]

Varieties: Prunus serotina Ehrhart var. serotina; Prunus serotina Ehrhart var. eximia (Little) Small[1]

Description

P. serotina is a perennial shrub/tree of the Rosaceae family native to North America and Canada.[2]

Distribution

P. serotina is found in the eastern half of the United States excluding South Dakota, as well as the British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec regions of Canada.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

P. serotina proliferates in rich coves, bottomlands, northern hardwood forests, and in a wide variety of lower elevation habitats from dry to mesic, and weedy in fencerows.[3] Specimens have been collected from habitats that include wet woods, sandpine woods, longleaf pine wiregrass scrub oak stand, dense swampy forest, open woodland, mesic mixed hardwoods, dry long leaf pine sandhills, hammock, thin stand of planted slash pine, dry mesic harwood forests, slope of narrow ravine, river bank, and semi shaded moist loamy sand in open woodland.[4]

P. serotina has shown regrowth in reestablished longleaf woodlands in South Carolina coastal plains communities, making it a post-agricultural woodland indicator species.[5] It exhibits no response to soil disturbance by improvement logging in Mississippi.[6]

Prunus serotina is an indicator species for the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[7]

Phenology

P. serotina has been observed to flower February through April.[8] This tree sometimes reaches a height of 90 feet and a maximum trunk diameter of 4 feet. The trunk is straight and covered with rough black bark, but the young branches are smooth and reddish. The smooth shining leaves are about 2 to 5 inches long. The long drooping clusters of small white flowers are borne at the ends of the branches, usually during May. The cherries, which ripen about August or September, are round, black, or very dark purple, about the size of a pea, and have a sweet, slightly astringent taste.[9]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by consumption by vertebrates.[10]

Fire ecology

Populations of Prunus serotina have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[11][12][13]

Herbivory and toxicology

Prunus serotina has been observed to host spittle bugs such as Clastoptera proteus (family Clastopteridae), ground bees from the Andrenidae family such as Andrena crataegi, A. forbesii, A. neonana, and Perdita bradley, aphids from the Aphididae family such as Aphis sp. and Myzus sp., leafhoppers from the Cicadellidae family such as Eratoneura ardens, Erythroneura comes, E. elegans, E. tricincta and Graphocephala coccinea, sweat bees such as Lasioglossum cinctipes (family Halictidae), treehoppers from the Membracidae family such as Entylia carinata, Micrutalis calva, and Telamona monticola, plant bugs such as Psallus variabilis (family Miridae), moths such as Furcula borealis (family Notodontidae), and true bugs such as Zelus luridus (family Reduviidae).[14] P. serotina is a bird-dispersed species.[15] It also serves as the main host plant for the eastern tent caterpillar.[16] This species is a larval host for tiger swallowtail, mourning cloak, and white admiral butterflies.[17]

Diseases and parasites

P. serotina is susceptible to the black knot fungus.[16] The parasitic species Phoradendron leucarpum or American Mistletoe has been observed on the P. serotina branches.[17]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

A bark tea was used in Appalachia to treat coughs, colds, measles, and relieve pain and muscle soreness, treat fever, intestinal worms, indigestion, and tuberculosis. The berries were used in teas to treat diarrhea.[18]

The fruit was used in jellies or eaten fresh.[19]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=PRSES

- ↑

- ↑ URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, O. Lakela, Frank Almeda, Richar Mitchell, Robert lazor, L.R. FOx, J. Harrison, R. Garren, Patricia Elliot, Gary Knight, Gwynn W. Ramsey, H. Larry E. Stripling, Mr. H.A. Davis, Mrs. H.A. Davis, S.W. Leonard, Wilson Baker, Alush Shilom Ton, R. Komarek, Ed Keppner, Lisa Keppner, K. MacClendon, T. MacClendon, Geo. Wilder, Albert B. Pittman, Herrick H.K. Brown, R. Kral, Dorothy Cladin, Pete Mazzeo, lizabeth Gibson, Dick Harlow, Angus Gholson, B. Boothe, A. Sagastegui, J. Mestacere, M. Diestra. States and counties: Florida (Franklin, Washington, Jefferson, Leon, Jackson, Hillsborough, Union, Marion, Duval, Liberty, Madison, Walton, Gadsden, Wakulla, Bay, Calhoun, Holmes, Volusia, Putnam, St. John, Escambia, Santa Rosa) Georgia (Thomas, Grady,Marion, Rockdale, Baker) South Carolina (Lexington) Virgin Islands.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., J.L. Orrock, E.I. Damschen, C.D. Collins, P.G. Hahn, W.B. Mattingly, J.W. Veldman, and J.L. Walker. (2014). Land-Use History and Contemporary Management Inform an Ecological Reference Model for Longleaf Pine Woodland Understory Plant Communities. PLoS ONE 9(1): e86604.

- ↑ McComb, W.C. and R.E. Noble. (1982). Response of Understory Vegetation to Improvement Cutting and Physiographic Site in Two Mid-South Forest Stands. Southern Appalachian Botanical Society 47(1):60-77.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 24 MAY 2018

- ↑ Sievers, A. F. (1930). American medicinal plants of commercial importance. Washington, USDA.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Leck, M. A. and C. F. Leck (1998). "A ten-year seed bank study of old field succession in central New Jersey." The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 125(1): 11-32.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 USDA Forest Service (1989). Insects and diseases of trees in the South. USDA Forest Service, Atlanta, GA. Protection Report R8-PR 16. F. S. S. Region: 98.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Observation by Jennifer Pell, comment by Jenny Jeanette Welch, Oak Hill Fl., February 22, 2018, posted to Florida Flora and Ecosystematics Facebook Group. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "FFE" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.

- ↑ Fernald, et al. 1958. Edible Plants of Eastern North America. Harper and Row Publishers, New York.