Polypremum procumbens

| Polypremum procumbens | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta – Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Scrophulariales |

| Family: | Buddlejaceae |

| Genus: | Polypremum |

| Species: | P. procumbens |

| Binomial name | |

| Polypremum procumbens L. | |

| |

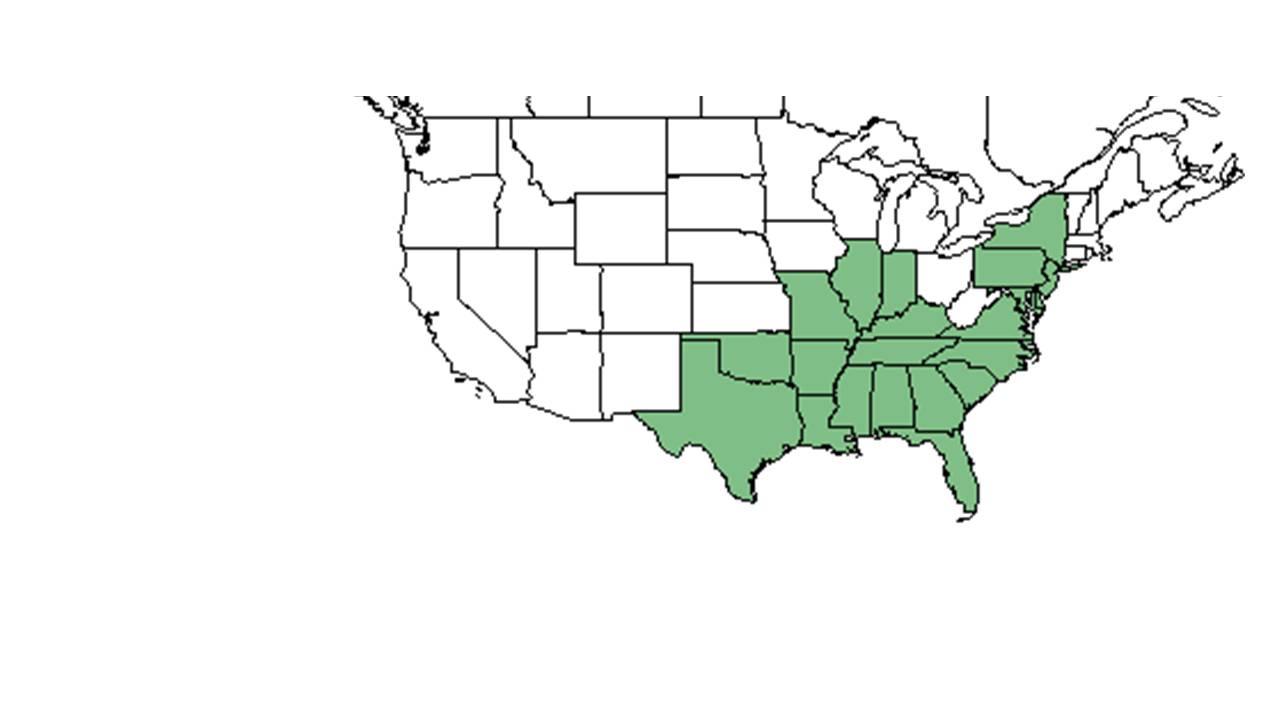

| Natural range of Polypremum procumbens from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common names: polypremum, juniperleaf, rustweed

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

"Perennial, glabrous herb with radially ascending or repent branches from a central crown. Leaves opposite, linear, 1-2.5 cm long, 0.5-2 mm wide, acute. Inflorescence a terminal leafy cyme. Flowers actinomorphic, sessile or on pedicels less than 0.5 mm long. Calyx divided to near the base, teeth 4, subulate, 2-3 mm long; corolla divided 1/3 in length, 4-lobed, white, rotate; stamens 4, included. Capsule 1.5-2.5 mm long; seeds yellow, angulate, more or less square, microscopically pitted, 0.3-0.4 mm long."[2]

Distribution

Ecology

Habitat

In the Coastal Plain in Florida and Georgia, P. procumbens can be found near streamlet crossings in open woodlands, well drained sandy soils of citrus furrows, annually burned savannas, sandy shores of karst ponds, annually burned longleaf pinelands, well drained uplands, and coastal dunes.[3] It can also be found in compacted soils of roadways, frequently mowed lawns, and roadside depressions.

P. procumbens has shown regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine habitats that were disturbed by agriculture, making it a possible indicator species for post-agricultural woodlands.[4]

It increased its frequency or was unaffected by roller chopping and disturbance by a KG blade in east Texas Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forests.[5]

Associated species include Lindernia, Murdannia, Kyllinga and Sida.[3]

Soil types include loamy sand and moist loam.[3]

Phenology

P. procumbens been observed flowering from May to September with peak inflorescence in July.[6][3] Fruiting has been observed in July.[3]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[7]

Seed bank and germination

It was found viable in the seed bank of a pine flatwoods in Florida but only one year following fire.[8] Commonly found in seed banks of disturbed areas,[9] one early 2000s study confirmed P. procumbens to be a dominant species in restoration soil seedbanks.[10] In a longleaf pine community in southwestern Georgia and in shrub dominated bays in eastern South Carolina, P. procumbens was found in the seedbank.[11] [12]

Fire ecology

Populations of Polypremum procumbens have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[13][14]

Pollination

Polypremum procumbens has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host sweat bees such the Lasioglossum nymphalis (family Halictidae), leafcutting bees such as Megachile brevis pseudobrevis (family Megachilidae), wasps such as Stenodynerus fundatiformis (family Vespidae), and thread-waisted wasps from the Sphecidae family such as Cerceris blakei, and Microbembex monodonta.[15] Deyrup observed the sweat bee Dialictus nymphalis on P. procumbens.[16]

Herbivory and toxicology

Cover of P. procumbens decreased significantly through time after three grazing treatments (no grazing by deer or cattle, grazing by deer, or grazing by deer and cattle) in thinned and clearcut forested areas.[17]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 835. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: July 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Cecil R Slaughter, Dianne Hall, R. A. Norris, R. Komarek, R. F. Doren, S. W. Leonard, J. Mickel, Thomas E. Miller, Robert K. Godfrey. States and Counties: Florida: Duval, Gadsden, Jefferson, Leon, Polk, St. Johns, Wakulla. Georgia: Grady, Thomas. Mexico. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Stransky, J.J., J.C. Huntley, and Wanda J. Risner. (1986). Net Community Production Dynamics in the Herb-Shrub Stratum of a Loblolly Pine-Hardwood Forest: Effects of CLearcutting and Site Preparation. Gen. Tech. Rep. SO-61. New Orleans, LA: U.S. Dept of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Forest Experiment Station. 11 p.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Maliakal, S.K., E.S. Menges and J.S. Denslow. 2000. Community composition and regeneration of Lake Wales Ridge wiregrass flatwoods in retlation to time-since-fire. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 127:125-138.

- ↑ Maliakal, S. K., E. S. Menges, et al. (2000). "Community composition and regeneration of Lake Wales Ridge wiregrass flatwoods in relation to time-since-rire " The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 127: 125-138

- ↑ Jenkins, Amy Miller. Seed banking and vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae in pasture restoration in central Florida. University of Florida. 2003.

- ↑ Andreu, M. G., et al. 2009. Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in southwest Georgia? Restoration Ecology 17:586-596.

- ↑ Navarra, J. J. and P. F. Quintana-Ascencio 2012. Spatial pattern and composition of the Florida scrub seed bank and vegetation along an anthropegenic disturbance gradient. Applied Vegetation Science 15:349-358.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Deyrup, M. J. E., and Beth Norden (2002). "The diversity and floral hosts of bees at the Archbold Biological Station, Florida (Hymenoptera: Apoidea)." Insecta mundi 16(1-3).

- ↑ Brockway, D. G. and C. E. Lewis (2003). "Influence of deer, cattle grazing and timber harvest on plant species diversity in a longleaf pine bluestem ecosystem." Forest Ecology and Management 175: 49-69.