Pityopsis graminifolia

| Pityopsis graminifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Michelle Smith | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Pityopsis |

| Species: | P. graminifolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Pityopsis graminifolia (Michx.) Nutt. | |

| |

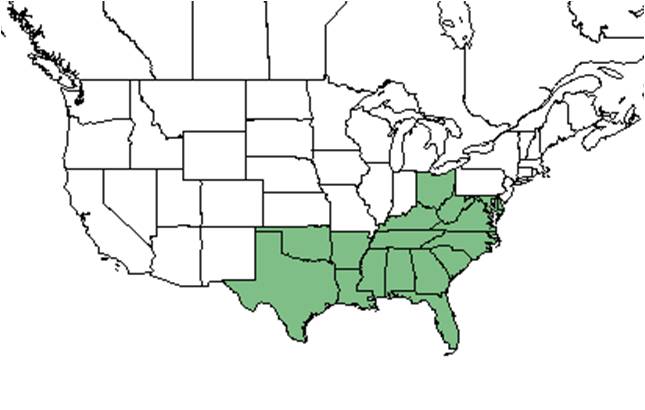

| Natural range of Pityopsis graminifolia from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: narrowleaf silkgrass

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Pityopsis graminifolia (Michaux) Nuttall var. graminifolia[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

Pityopsis graminifolia is a cepitose, sericeous-floccose perennial with an erect, 4-8 dm tall stem and appressed or ascending leaves. The leaves are linear, grass-like, and entire. They are basal parallel-veined, 1-3.5 dm long and 3-10 mm wide. The heads number three to many and grow in corymbs. The involucres are cylindric to campanulate, 7-8 mm long, and 5-8 mm broad. The bracts are linear, appressed, and stipitate-glandular. The rays are numbered 4-10 and 1-1.5 cm long. The nutlets are reddish-brown to black, fusiform, pubescent, and 2.3-3 mm long. The pappus is colored tan to cinnamon and 4.5-6 mm long.[1]

Pityopsis graminifolia does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its fibrous roots.[2] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have a water content of 58.6% (ranking 65 out of 100 species studied).[2]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Pityopsis graminifolia has fibrous roots with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.703 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 135 mg g-1.[3]

Distribution

Silkgrass tends to be found in disturbed areas, open fields, and young tree plantations in the longleaf pine forest range from Virginia to Florida to Texas.[4][5][6]

Ecology

Habitat

Pityopsis graminifolia is restricted to native groundcover with a statistical affinity in upland pinelands of South Georgia.[7] This species is considered an indicator of non-agriculture history in frequently burned longleaf pine habitats.[8] Additionally, this species has shown regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine woodlands that were disturbed by agricultural practices in South Carolina coastal plain communities, making it also possibly an indicator species for post-agricultural woodlands.[9] It has also increased its foliar cover in response to clearcutting and roller chopping in north Florida pinelands.[10] P. graminifolia is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills, North Florida Subxeric Sandhills, Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands, Panhandle Silty Longleaf Woodlands, Xeric Flatwoods, North Florida Mesic Flatwoods, Central Florida Flatwoods/Prairies, and Upper Panhandle Savannas community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[11]

P. graminifolia became absent in response to soil disturbance by heavy silvilculture in North Carolina longleaf sites.[12] It became absent or decreased its occurrence in response to agriculture in southwest Georgia pinelands.[7] The species became absent in response to military training in west Georgia longleaf pine forests.[13] Additionally, its frequency and density was reduced in response to roller chopping in northwest Florida sandhills.[14] P. graminifolia has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished habitats that were disturbed by these practices.

It exhibits no response to soil disturbance by clearcutting, bracke seeding, single roller chopping, broadcast seeding, high-severity burns, and salvage logging in central Florida.[15] P. graminifolia also does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods forests.[16]

The plant has decreased its occurrence or been unaffected by roller chopping in south Florida. It has shown resistance to regrowth or been unaffected in response to reestablished habitat that was disturbed by this practice.[17]

Phenology

P. graminifolia has been observed flowering in January, April, May, July, and from September to December.[18]

Seed dispersal

This species disperses by wind.[19]

Fire ecology

May or may not show fire-stimulated flowering, depending on variety or ecotype.[20] [21] [22] Populations of Pityopsis graminifolia have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[23][24][25]

Pollination

Pityopsis graminifolia has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host ground nesting bees such as Andrena fulvipennis (family Andrenidae), plasterer bees such as Colletes mandibularis (family Colletidae), wasps such as Leucospis robertsoni (family Leucospididae), bees from the Apidae family such as Bombus impatiens, Epeolus pusillus, and Nomada fervida, sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Agapostemon splendens, Augochlora pura, Augochlorella aurata, Augochloropsis anonyma, A. metallica, A. sumptuosa, Halictus poeyi, Lasioglossum miniatulus, L. nymphalis, L. pectoralis, and L. placidensis, leafcutting bees from the Megachilidae family such as Anthidiellum notatum rufomaculatum, A. perplexum, Anthidium maculifrons, Coelioxys octodentata, C. sayi, C. texana, Dianthidium floridiense, Megachile albitarsis, M. brevis pseudobrevis, M. georgica, M. inimica, M. mendica, M. petulans, and M. pruina, thread-waisted wasps from the Sphecidae family such as Bicyrtes capnoptera, Cerceris tolteca, Philanthus ventilabris, Prionyx thomae, and Trypargilum clavatum johannis, as well as wasps from the Vespidae family such as Parancistrocerus salcularis rufulus, and Stenodynerus beameri[26] Additionally, P. graminifolia has been observed to host ground nesting bees from the Andrenidae family such as Perdita blatchleyi, P. boltoniae, P. consobrina, P. georgica, P. graenicheri, P. octomaculata, and Pseudopanurgus solidaginis, aphids such as Uroleucon sp. (family Aphididae), bees from the Apidae family such as Melissodes dentiventris and Triepeolus atripes, plasterer bees such as Colletes americanus (family Colletidae), sweat bees such asDieunomia nevadensis (family Halictidae), as well as leafcutting bees such as Coelioxys modesta (family Megachilidae).[27]

Herbivory and toxicology

Buds fed upon by white-tailed deer.[28] Common grasshoppers, including Melanopus angustipennis as well as grasshoppers in the subfamilies Melanoplinae and Cyrtacanthacridinae, are mixed feeders and often feed on Pityopsis graminifolia. This plant is quite susceptible to herbivory, but overall herbivory has weak effects on biomass and mortality.[8]

Silkgrass is a known primary forage for gopher tortoises.[29][30][31]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ Denhof, Carol. 2020. Plant Spotlight Pityopsis graminifolia (Michx.) Nutt. Silkgrass Aster Family - Asteraceae. The Longleaf Leader. Vol. XIII, Issue 3. Pg. 7

- ↑ Miller, J.H. and K.V. Miller. 2005. Forest Plants of the Southeast and their Wildlife Uses. The University of Georgia Press. Athens, GA. 454pp.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. 2020. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 11 February 2-2-). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ostertag, T.E., and K.M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Pages 109–120 in R.E. Masters and K.E.M. Galley (eds.). Proceedings of the 23rd Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference: Fire in Grassland and Shrubland Ecosystems.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Hahn, P. C. and J. L. Orrock (2015). "Land-use legacies and present fire regimes interact to mediate herbivory by altering the neighboring plant community." Oikos 124: 497-506.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Lewis, C.E., G.W. Tanner, and W.S. Terry. (1988). Plant responses to pine management and deferred-rotation grazing in north Florida. Journal of Range Management 41(6):460-465.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Cohen, S., R. Braham, and F. Sanchez. (2004). Seed Bank Viability in Disturbed Longleaf Pine Sites. Restoration Ecology 12(4):503-515.

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Hebb, E.A. (1971). Site Preparation Decreases Game Food Plants in Florida Sandhills. The Journal of Wildlife Management 35(1):155-162.

- ↑ Greenberg, C.H., D.G. Neary, L.D. Harris, and S.P. Linda. (1995). Vegetation Recovery Following High-intensity Wildfire and Silvicultural Treatments in Sand Pine Scrub. American Midland Naturalist 133(1):149-163.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Lewis, C.E. (1970). Responses to Chopping and Rock Phosphate on South Florida Ranges. Journal of Range Management 23(4):276-282.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Brewer J.S. 1995. The relationship between soil fertility and fire-stimulated floral induction in two populations of grass-leaved golden aster, Pityopsis graminifolia. Oikos 74:45-54.

- ↑ Brewer, J. S. 2009. Geographic variation in flowering responses to fire and season of clipping in a fire-adapted plant. American Midland Naturalist 160:235-249.

- ↑ Gowe, A.K. and J. S. Brewer. 2005. The evolution of fire-dependent flowering in goldenasters (Pityopsis spp.). Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 132:384-400.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- ↑ Brewer J.S. and Platt W.J. 1994. Effects of fire season and herbivory on reproductive success of a clonal forb, Pityopsis graminifolia. Journal of Ecology 82:665-675.

- ↑ Denhof, Carol. 2020. Plant Spotlight Pityopsis graminifolia (Michx.) Nutt. Silkgrass Aster Family - Asteraceae. The Longleaf Leader. Vol. XIII, Issue 3. Pg. 7

- ↑ Miller, J.H. and K.V. Miller. 2005. Forest Plants of the Southeast and their Wildlife Uses. The University of Georgia Press. Athens, GA. 454pp.

- ↑ USDA, NRCS. 2020. The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 11 February 2-2-). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.