Monotropa uniflora

| Monotropa uniflora | |

|---|---|

Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination

| |

| Photo was taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Monotropaceae |

| Genus: | Monotropa |

| Species: | M. uniflora |

| Binomial name | |

| Monotropa uniflora L. | |

| |

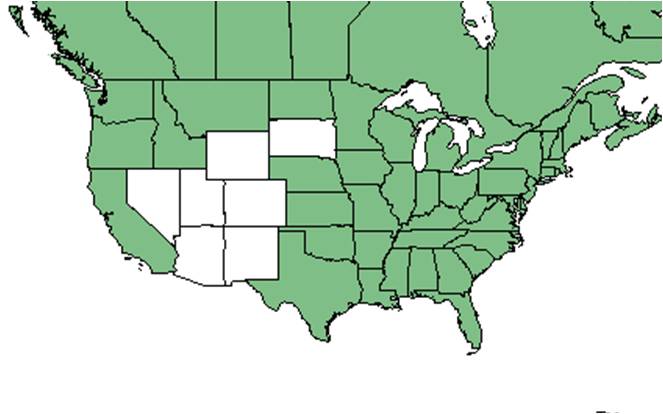

| Natural range of Monotropa uniflora from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Indian pipes[1]

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

A description of Monotropa uniflora is provided in The Flora of North America.

M. unitropa has a glabrous stem and solitary flower, with white coloration when fresh and black as it ages.[1]

Distribution

This plant ranges from Labrador and Alaska, south to southern Florida, Texas, and California. There are disjunct populations in southern Mexico, Central America, South America, and eastern Asia.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

This species can be found in mixed woodlands, mesic bluffs, ravine edges, along swamps, pine scrub, and hardwood hammock edges.[2] Observed growing in shaded areas, M. uniflora occurs in moist and dry sand, sandy loam, and rich hummus.[2] It is also found in human disturbed habitats such as hiking trails, residential backyards, and front lawns.[2]

M. uniflora became absent or decreased its occurrence in response to disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia pinelands. It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished pinelands that were disturbed by agricultural practices.[3]

Associated species include Carya, Magnolia, Quercus, Habernaria quinqueseta, Cypress, Burmannia biflora, Pinus clausa, Quercus myrtifolia, and Q. maritima.[2]

Phenology

This species flowers from June through October and fruits from August through November.[1]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity.[4]

Fire ecology

Populations of Monotropa uniflora have been known to persist through repeated annual burning.[5]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

M. uniflora should avoid soil disturbance by agriculture to conserve its presence in pine communities.[3]

Cultural use

Powdered root was used in treating epilepsy and seizures in children, and the juice was used in treating a variety of eye problems. The entire plant was dried and used as a opium replacement for pain relief and insomnia.[6]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Herbert Kessler, Jacob Kimel, R.K. Godfrey, John B. Nelson, George R. Cooley, D. B. Ward, J. Beckner, Lovett E. Williams, Michael Castagna, Travis MacClendon, K. MacClendon, P. Howell, B. Thomas, G. Wilder, R. Komarek, Kathleen Brady, Ed Keppner, and Lisa Keppner. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Calhoun, Gadsden, Hernando, Leon, Liberty, Marion, and Wakulla. Georgia: Grady.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings 23: 109-120.

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Platt, W.J., R. Carter, G. Nelson, W. Baker, S. Hermann, J. Kane, L. Anderson, M. Smith, K. Robertson. 2021. Unpublished species list of Wade Tract old-growth longleaf pine savanna, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Korchmal, Arnold & Connie. 1973. A Guide to the Medicinal Plants of the United States. The New York Times Book Company, New York.