Liatris tenuifolia

| Liatris tenuifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae ⁄ Compositae |

| Genus: | Liatris |

| Species: | L. tenuifolia |

| Binomial name | |

| Liatris tenuifolia Nutt. | |

| |

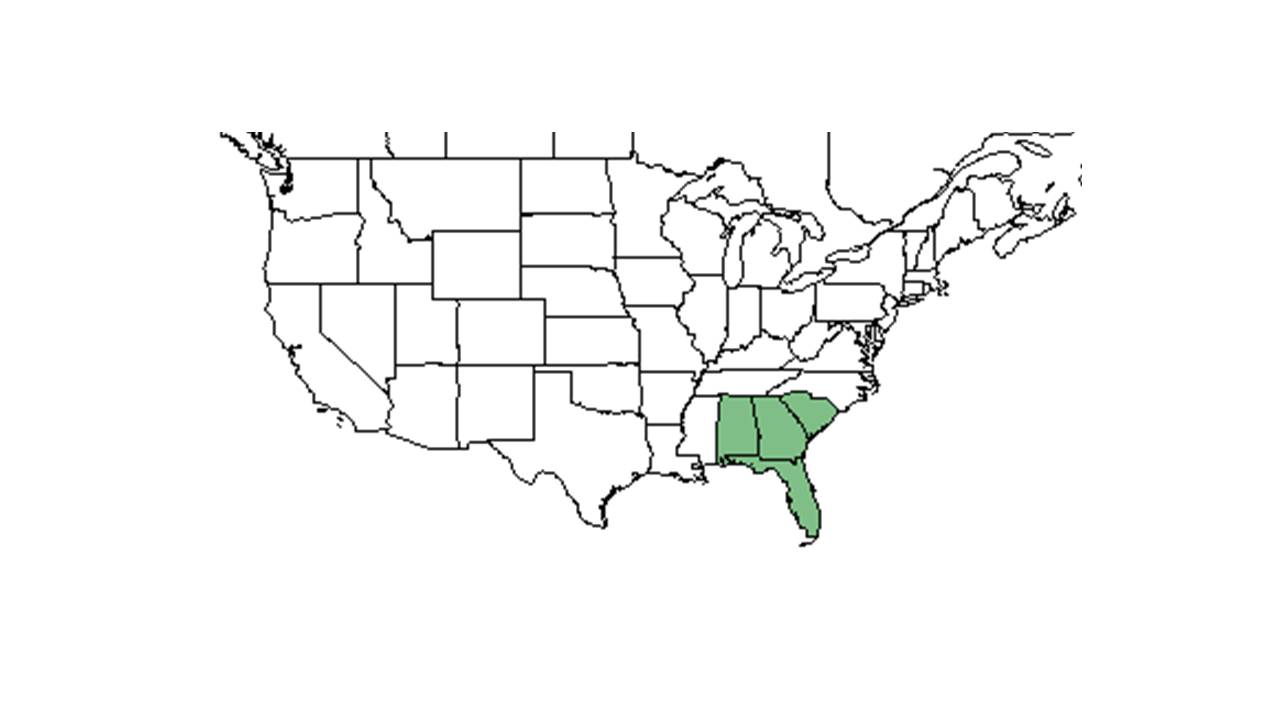

| Natural range of Liatris tenuifolia from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Shortleaf blazing star

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Liatris tenuifolia Nuttall var. tenuifolia[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

A description of Liatris tenuifolia is provided in The Flora of North America.

The root system of Liatris tenuifolia includes corms which store non-structural carbohydrates (NSC) important for both resprouting following fire and persisting during long periods of fire exclusion.[2]. Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an NSC concentration of 217.4 mg/g (ranking 20 out of 100 species studied) and water content of 75% (ranking 28 out of 100 species studied).[2]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Liatris tenuifolia has corms with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.846 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 217.4 mg g-1.[3]

Distribution

L. tenuifolia ranges from South Carolina, south to southern Florida, and west to Alabama.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

Habitats of L. tenuifolia include longleaf pine-turkey oak sand ridge, dry Quercus laurifolia hammock, scrub-oak ridge, sandhills, semi-boggy areas, wet pine flatwoods,course sand and scrub oak barren, and annually burned pinelands.[4] Human disturbed areas include moist loamy sand of roadside depression, dry sand of scrubby ridges along roads, bordering pine flatwoods along the road, sandy clearings, open fields, and on the edge of clearing banks of rivers.[4] Soil types include moist loamy sand, dry sand, coarse sand, gravelly sandy soil, white sand, sandy loam, and sandy-peaty soils.[4] Availability of nitrogen, pH, organic matter, and inorganic nutrients such as (Ca, K, Mg, and P) have been observed to be concentrated at low levels in the soil.[5]

L. tenuifolia was found to increase in occurrence in response to soil disturbance by agriculture in southwest Georgia. It has shown regrowth in reestablished pinelands that were disturbed by agricultural practices.[6]

Plants associated include Liatris, Andropogon, Quercus geminata, Quercus laevis, Quercus laurifolia, Carya floridana, Crataegus, Chrysopsis, Aristida, Balduina, Carphephorus, Penstemon, Polygonella, Pinus clausa, Pinus palustris, Solidago, Pityopsis, Carphephorus odoratissimus, Illex glabra, Serenoa repens, Euthamia minor, Panicum rigidulum, Pterocaulon pyncnostachyum, Elephantopus elatus and Aster dumosus.[4]

Liatrus tenuifolia var. tenuifolia is frequent and abundant in the Peninsula Xeric Sandhills and North Florida Subxeric Sandhills community types as described in Carr et al. (2010).[7]

Liatris tenuifolia var. quadriflora is an indicator species for the Xeric Flathills community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[8]

Phenology

L. tenuifolia flowers August through November.[4][9]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by wind.[10]

Seed bank and germination

Fire improves seedling recruitment.[11]

Fire ecology

L. tenuifolia responds positively to conditions following a burn by increased vegetative growth and flowering and typically blooms within a year or so following fire.[5] There is an increase in growth and flowering in burned sandhill sites located in south-central Florida.[5] It also has been found in burned and unburned patches of degraded longleaf pine sandhill.[12] Populations of Liatris tenuifolia have been known to persist through repeated annual burns.[13]

Herbivory and toxicology

Liatris tenuifolia was observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host thread-waisted wasps such as Ammophila procera (family Sphecidae), bees from the Apidae family such as Apis mellifera, Bombus impatiens, and B. pennsylvanicus, as well as sweat bees from the Halictidae family such as Agapostemon splendens, Augochlorella aurata, and Augochloropsis sumptuosa, and leafcutting bees from the Megachilidae family such as Coelioxys mexicana, C. sayi, Megachile albitarsis, M. brevis pseudobrevis, M. brimleyi, M. petulans, and M. texana.[14] Additionally, L. tenuifolia has been observed to host the leafcutting bee Megachile albitarsis (family Megachilidae).[15]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: July 2015. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Ann F. Johnson, R.K. Godfrey, R. Kral, J. P. Gillespie, James D. Ray, Jr., Olga Lakela, Jackie Patman, R L Lazor, V. I. Sullivan, D. B. Ward, Tin Myint, Jame Amoroso, Bian Tan, Paul L. Redfearn, Jr., Sidney McDaniel, Bruce Hansen, JoAnn Hansen, A. F. Clewell, John Morrill, William B. Fox, W. D. Reese, Nancy Z. Edmondson, P. Genelle, G. Fleming, Elmer C. Prichard, Richard D. Houk, O. Lakela, R. Komarek, R.A. Norris, Cecil R Slaughter, Tara Baridi, Rex Ellis. States and Counties: Florida: Bay, Brevard, Citrus, Columbia, Dixie, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Hernando, Hillsborough, Holmes, Jackson, Lafayette, Liberty, Leon, Madison, Okaloosa, Osceola, Polk Putnam, Santa Rosa, Taylor, Union, Wakulla, Walton. Georgia: Thomas. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Anderson, R. C. and E. S. Menges (1997). "Effects of fire on sandhill herbs: nutrients, mycorrhizae, and biomass allocation." American Journal of Botany 84: 938-948.

- ↑ Ostertag, T. E. and K. M. Robertson. 2007. A comparison of native versus old-field vegetation in upland pinelands managed with frequent fire, South Georgia, USA. Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference Proceedings 23: 109-120

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Whelan, W.A. 1970. Patterns of recruitment to plant populations after fire in western Australia and Florida. Proceedings of the Ecological Society of Australia 14:169-178.

- ↑ Heuberger, K. A. and F. E. Putz (2003). "Fire in the suburbs: ecological impacts of prescribed fire in small remnants of longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhill." Restoration Ecology 11: 72-81.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]