Lachnanthes caroliniana

| Lachnanthes caroliniana | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Gil Nelson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida – Monocotyledons |

| Order: | Liliales |

| Family: | Haemodoraceae |

| Genus: | Lachnanthes |

| Species: | L. caroliniana |

| Binomial name | |

| Lachnanthes caroliniana (Lam.) Dandy | |

| |

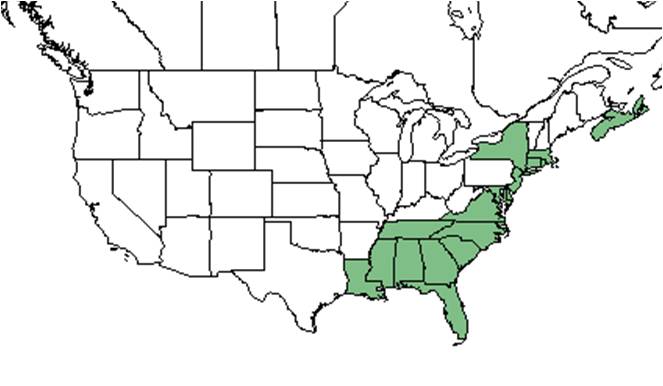

| Natural range of Lachnanthes caroliniana from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: Redroot[1]

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: Lachnanthes tinctoria (J.F. Gmelin) Elliott; Gyrotheca tinctoria (J.F. Gmelin) Salisbury.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

L. caroliniana is a perennial monocot with slender rhizomes and notable red roots. The flower stalk can reach up to three feet tall and has gray hairs along the top.[2]

"Roots and rhizomes red. Stems pubescent only toward the inflorescence, glabrous below. Leaves 0.5-1.5 cm wide. Inflorescence convex. At first very compact and appearing head-like, expanding and become slightly open, the branches corymbosely arranged, each forming a compact helicoids cyme. Sepals 4-7 mm long, less than 1 mm wide, yellowish to brownish; petals 7-9 mm long, 1-1.5 mm wide, erect or slightly bent outward in age; stamens 3, exserted 1-2 mm, anthers at first straight, curling in age; styles slightly longer than the stamens; ovary inferior. Capsule oblate, 2-5 mm long, dehiscent to base. Seeds blackish brown, circular, 2-2.5 mm in diam., flat, surface uneven."[3]

Distribution

It can be found in coastal environments from Louisiana to Florida and north to Massachusetts, with disjunct populations in Tennessee, Virginia, and southern Novia Scotia, and can also be found in Cuba.[4]

Ecology

Habitat

Habitats are typically wet, acidic, nutrient-poor areas such as mesic and wet flatwoods, wet prairies, and seasonally inundated shorelines.[5] It can commonly be found in disturbed areas such as trails, ditches, fire lanes.[6] and has been observed by Jean Huffman to form dense stands following hog-rooting.

It can become a serious weed in cranberry bogs and newly established pastures.[7][8]

L. caroliniana does not respond to soil disturbance by clearcutting and chopping in North Florida flatwoods forests.[9] Furthermore, it was found to be neutral in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances.[10]

Associated species include Panicum hemitomon, Hypericum edisonianum, and Panicum abscissum.[11]

Phenology

The white flowers are perfect and actinomorphic with a homoclamydeous imbricate perianth, 3 basifixed stamens, and an inferior, globose, slightly 3-lobed ovary [12] and arranged in a corymb.[7] The seed is a reddish 3 lobed capsule.[5] L. caroliniana has been observed to flower from May to July.[13]

Seed dispersal

Seeds are dispersed locally by gravity.[5]

Seed bank and germination

In the southern part of its range, it is capable of producing a substantial seed bank.[5] In an ex-situ germination experiment in the marsh banks of southern Georgia, seedling germination was significantly increased by adding nitrogen plus phosphorus to a moist environment.[14]

Fire ecology

It is observed growing in a pond pine/titi peat swamp that was burned by a lightning-set wildfire four months previously.[6] Hinman and Brewer (2007) observed L. caroliniana to have a reduction of flowering stalk density following a fire. This study also showed a significant decline between the initial and pre-fire census and a significant increase between the immediate and second post-fire census.

Herbivory and toxicology

L. caroliniana is an important food source to wigeons, gadwalls, pintails, sandhill cranes, and mallards, which eat the seeds and rhizomes (Landers et al. 1976). This species contains photodynamic toxins that limit herbivory by insects and some vertebrates but not waterfowl.[15] L. caroliniana has been observed to host assassin bugs such as Zelus cervicalis (family Reduviidae).[16]

Additionally, L. caroliniana has been observed at the Archbold Biological Station to host the following species:[17]

Bees from the family Apidae: Apis mellifera, Bombus impatiens, B. pennsylvanicus, Mellisodes communis

Sweat bees from the family Halictidae: Agapostemon splendens, Augochloropsis metallica, A. sumptuosa, Lasioglossum coreopsis, L. nelumbonis

Leafcutting bees from the family Megachilidae: Anthidiellum perplexum, Anthidium maculifrons, Coelioxys mexicana, C. octodentata, C. sayi, Megachile albitarsis, M. brevis pseudobrevis, M. georgica, M. mendica, M. petulans, M. texana

Thread-waisted wasps from the family Sphecidae: Philanthus ventilabris

Wasps from the family Vespidae: Polistes bellicosus, P. fuscatus

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

Eutrophication from agriculture and urbanization has had a detrimental impact on Coastal Plain plant communities in Long Island and New Jersey.[18]

In Nova Scotia, it is listed as a threatened species.[4]

Cultural use

Historically, it was used by Native Americans as a narcotic and to treat ailments.[19]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

Hinman, S. E. and J. S. Brewer (2007). "Responses of Two Frequently-Burned Wet Pine Savannas to an Extended Period without Fire." The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 134(4): 512-526.

Landers, J. L., A. S. Johnson, et al. (1976). "Duck Foods in Managed Tidal Impoundments in South Carolina." The Journal of Wildlife Management 40(4): 721-728.

Nichols, G.E. 1934. The influence of exposure to winter temperatures on seed germination in various native North American plants. Ecology 15:364-373.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ [[1]]Florida Department of Environmental Protection Accessed: January 9, 2016

- ↑ Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 323. Print.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 [[2]]Accessed January 9, 2016

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 [[3]]COSEWIC Accessed: January 9, 2016

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: January 2016. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Kathleen Craddock Burks, R. Komarek, Thomas E. Miller, R.A. Norris, Cecil R. Slaughter, Rodie White. States and Counties: Florida: Duval, Lafayette, Osceola, Santa Rosa, St. Johns, St. Lucie, Volusia, Wakulla. Georgia: Grady. Compiled by Tall Timbers Research Station and Land Conservancy.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 [[4]]Go Botany Accessed: January 10, 2016

- ↑ [[5]]University of Florida IFAS Extension Accessed: January 9, 2016

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ George, B. L. and E. S. Menges (1999). "Dynamics of Woody Bayhead Invasion into Seasonal Ponds in South Central Florida." Castanea 64(2): 130-137.

- ↑ Simpson, M. G. (1988). "Embryological Development of Lachnanthes caroliniana (Haemodoraceae)." American Journal of Botany 75(9): 1394-1408.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 12 DEC 2016

- ↑ Gerritsen, J. and H.S. Greening. 1989. Marsh Seed Banks of the Okefenokee Swamp: . Floristic Synthesis of North America (CD-ROM, Draft). Biota of North America Program, Chapel Hill, NC.

- ↑ Kornfeld, J.M. and Edwards, J.M. 1972. Investigation of photodynamic pigments in extracts of Lachnanthes tinctoria. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta 286:88.

- ↑ Discoverlife.org [6]

- ↑ Deyrup, M.A. and N.D. 2015. Database of observations of Hymenoptera visitations to flowers of plants on Archbold Biological Station, Florida, USA.

- ↑ Zaremba, R.E. and E.E. Lamont. 1993. The status of the Coastal Plain Pondshore community in New York. Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 120:180-187.

- ↑ Millspaugh, C.F. 1887. American Medicinal Plants. Caxton Press of Sherman, Philadelphia.