Hypericum gentianoides

Common name: orangegrass [1], pineweed, orangeweed[2]

| Hypericum gentianoides | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by Marilee Lovit at the GoBotany Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Theales |

| Family: | Clusiaceae |

| Genus: | Hypericum gentianoides |

| Species: | H. gentianoides |

| Binomial name | |

| Hypericum gentianoides L | |

| |

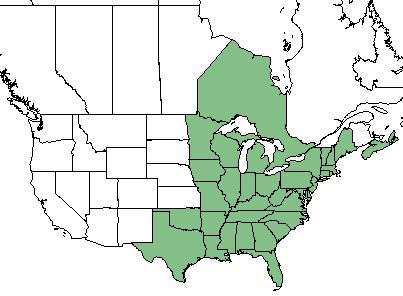

| Natural range of Hypericum gentianoides from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Sarothra gentianoides Linnaeus[2]

Varieties: none[2]

Description

H. gentianoides is an annual forb/herb of the Clusiaceae family native to North America and Canada.[1] It has scaly leaves that are arranged on erect and wiry branches. Flowers are tiny and yellow, and only open with sunlight. Fruit capsules are usually red in color.[3]

Distribution

H. gentianoides is found in the eastern half of the United States, as well as the Ontario region of Canada.[1] More specifically, it is distributed from Maine and Ontario west to Minnesota, and south to southern Florida and Texas.[2]

Ecology

Habitat

H. gentianoides proliferates in fields, rock outcrops, woodland borders, eroding areas, pond margins, and flatwoods.[2] It mostly grows in areas that are open with sandy or rocky soils; it can also tolerate partial shade.[3] Specimens have been collected from loamy loose sand, wet pine flatwoods, longleaf pine depression, and sandhills. [4]

H. gentianoides exhibited mixed responses to soil disturbance by agriculture in South Carolina longleaf pinelands. It has shown both resistance to regrowth and regrowth in reestablished native longleaf pine habitat that was disturbed by agricultural practices. In areas where it did exhibit regrowth it may be considered a post-agricultural woodland indicator species.[5][6] However, it was found to be unaffected by clearcutting and chopping in north Florida flatwoods forests.[7] H. gentianoides was found to be neutral in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances as well as in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[8]

It has been shown to significantly increase in frequency when the overstory is clearcut.[9] It also has been shown to respond positively to pine thinning as well as woody control.[10] It is listed by the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service as a facultative upland species, where it most often occurs in non-wetland habitats but can also occasionally be found in wetland habitats as well.[1]

Associated species includes Selaginella arenicola, Polygonella sp., and Stipulicida setacea.[4]

Phenology

Generally, H. gentianoides flowers from July until October.[2] It has been observed flowering in May through July and September. [11]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. [12]

Seed bank and germination

It was found to be a member of the seed bank at a loblolly pine restoration site in southwest Georgia even when it was not a component of the herbaceous vegetation.[13] Scarification of seeds has been shown to significantly increase the number of germinates rather than unscarified seeds.[14] Another study on early successional old field sites found H. gentianoides to germinate from the seed bank mostly from 5 and 15 year old sites.[15] As well, it was found to germinate exclusively from longleaf pine community types and not from scrub community types or ecotones.[16]

Fire ecology

H. gentianoides is very often found growing in firelanes.[17] It was also found in a study by Rodgers and Provencher that this species is fairly common in burned bluestem (Quercus incana) plots.[18] As well, it has been found to emerge in areas when there is a fire disturbance where it was not found before fire disturbance, and persist in the community over time.[19]

Herbivory and toxicology

Hypericum gentianoides consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for various large mammals and terrestrial birds.[20]

Diseases and parasites

It is a host plant for the parasitic Harper's dodder (Cuscuta harperi).[21]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

H. gentianoides is listed as endangered by the Iowa Department of Natural Resources Parks, Recreation, and Preserves Division.[1] It is also considered vulnerable in Michigan, imperiled in Vermont, critically imperiled in Oklahoma and Ontario, and an exotic species in the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island.[22]

Cultural use

For humans, it can be used medicinally as an asperient in inflammatory affections.[23] It was also historically known as a vulnerary traumatic that could be used in contusions and bruises or sprains by boiling and then applying the plant.[24]

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 USDA Plant Database https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=HYGE

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 [[1]] Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center. Accessed: May 23, 2019

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2018. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Leon Neel, Andre Clewell, R.F. Doren, R.K. Godfrey, Cecil Slaughter, Wilson Baker, Ann Johnson, John Nelson, Keith Bradley. States and counties: South Carolina (Dillon) Florida (Bay, Flagler, Duval, Leon, Wakulla, Franklin) Georgia (Baker, Thomas)

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A. and E.I. Damchen. (2011). Land-use history, historical connectivity, and land management interact to determine longleaf pine woodland understory richness and composition. Ecography 34: 257-266.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Moore, W.H., B.F. Swindel, and W.S. Terry. (1982). Vegetative Response to Clearcutting and Chopping in a North Florida Flatwoods Forest. Journal of Range Management 35(2):214-218.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Brockway, D. G. and C. E. Lewis (2003). "Influence of deer, cattle grazing and timber harvest on plant species diversity in a longleaf pine bluestem ecosystem." Forest Ecology and Management 175: 49-69.

- ↑ Harrington, T. B. (2011). "Overstory and understory relationships in longleaf pine plantations 14 years after thinning and woody control." Canadian Journal of Forest Research 41: 2301-2314.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 22 MAY 2018

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Andreu, M. G., et al. (2009). "Can managers bank on seed banks when restoring Pinus taeda L. plantations in Southwest Georgia?" Restoration Ecology 17: 586-596.

- ↑ Mou, P., et al. (2005). "Regeneration strategies, disturbance and plant interactions as organizers of vegetation spatial patterns in a pine forest." Landscape Ecology 20: 971-987.

- ↑ Oosting, H. J. and M. E. Humphreys (1940). "Buried viable seeds in a successional series of old field and forest soils." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 67(4): 253-273.

- ↑ Ruth, A. D., et al. (2008). "Seed bank dynamics of sand pine scrub and longleaf pine flatwoods of the Gulf Coastal Plain (Florida)." Ecological Restoration 26: 19-21.

- ↑ Clarke, G. L. and W. A. Patterson (2007). "The distribution of disturbance-dependent rare plants in a coastal Massachusetts sandplain: implications for conservation and management." Biological Conservation 136: 4-16.

- ↑ Rodgers, H. L. and L. Provencher (1999). "Analysis of Longleaf Pine Sandhill Vegetation in Northwest Florida." Castanea 64(2): 138-162.

- ↑ Taft, J. B. (2003). "Fire effects on community structure, composition, and diversity in a dry sandstone barrens." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 130: 170-192.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Costea, Mihai, et al. (2006). "Taxonomy of the Cuscuta pentagona complex (Convolvulaceae) in North America." SIDA Contributions to Botany 22(1): 151-175.

- ↑ [[2]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 23, 2019

- ↑ Porcher, F. P. (1869). Resources of the southern fields and forests, medical, economical, and agricultural. Richmond, VA, Order of the Surgeon-General.

- ↑ Rafinesque, C. S. (1828). Medical flora; or Manual of the medical botany of the United States of North America.