Gymnopogon ambiguus

| Gymnopohon ambiguus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Liliopsida – Monocotyledons |

| Order: | Poales |

| Family: | Poaceae ⁄ Gramineae |

| Genus: | Gymnopogon |

| Species: | G. ambiguus |

| Binomial name | |

| Gymnopogon ambiguus (Michx.) Britton, Sterns & Poggenb. | |

| |

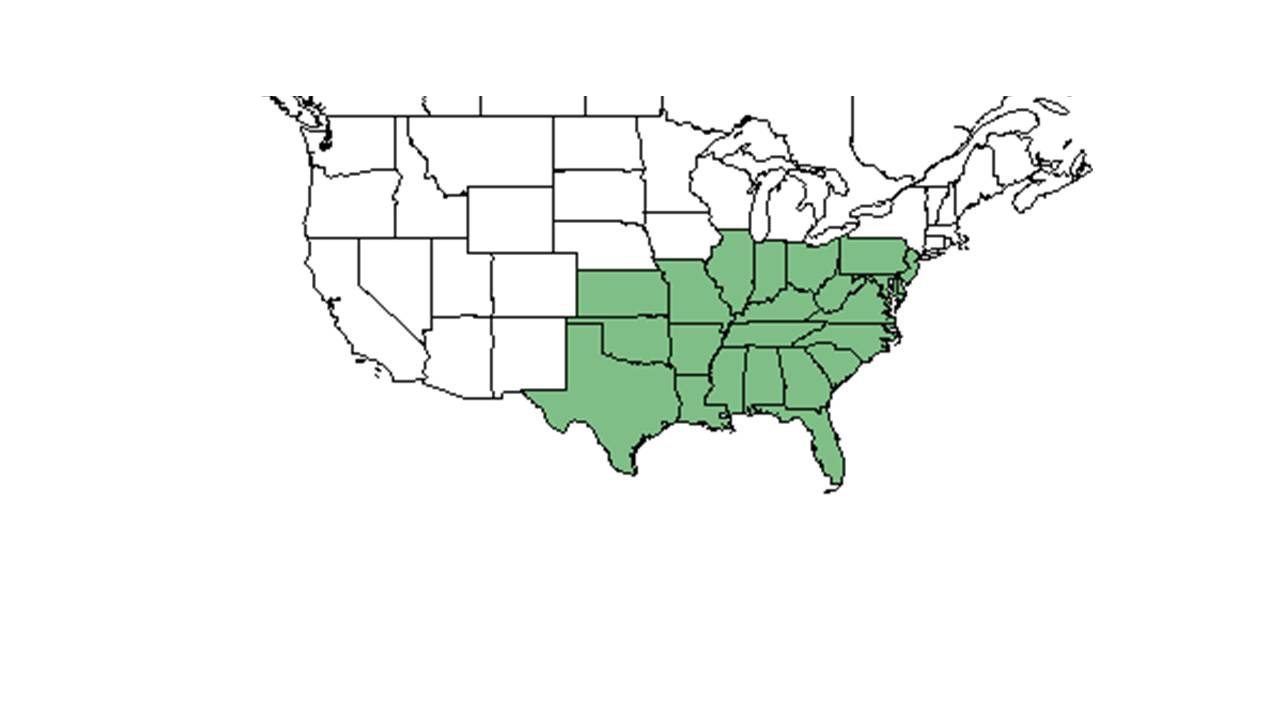

| Natural range of Gymnopogon ambiguus from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: bearded skeletongrass; eastern skeleton grass; eastern beard grass

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: none[1]

Description

"Tufted, rhizomatous, perennial; culms branching, nodes and internodes glabrous. Leaves cauline; blades glabrous on both surfaces, margins scaberulous, bases cordate; sheaths conspicuously overlapping, glabrous, usually pilose apically; ligules membranous, ciliolate, less than 0.4 mm long; collars usually pilose. Spikes racemose; branches spreading, flexuous, angled, scaberulous. Spikelets in two rows on one side of rachis, 1-flowered, occasionally a rudiment present in G. amibguus, appressed; pedicels angled, scaberulous, absent or to 1.5 mm long. Glumes 1-nerved, margins usually scarious; paleas 2-nerved, margins usually scarious, acute; callus usually bearded; rachilla prolonged or capped by sterile floret. Grain reddish, linear-ellipsoid." [2]

"Culms 3-7 dm tall. Blades to 6 cm long, 2-8 mm wide; ligules occasionally ciliate, 2.5 mm long. Spikelets beyond middle of spike only, 2.5-4.5 mm long. Glumes 2.5-4.5 mm long; lemmas pubescent apically, body 2-2.3 mm long, dorsal awns 1-3.5 mm long; paleas 2.2-3 mm long. Grain 1.8-2 mm long."[2]

Gymnopogon ambiguus does not have specialized underground storage units apart from its rhizomes.[3] Diaz-Toribio and Putz (2021) recorded this species to have an non-structural carbohydrate concentration of 21.7 mg/g (ranking 95 out of 100 species studied).[3]

According to Diaz-Torbio and Putz (2021), Gymnopogon ambiguus has rhizomes with a below-ground to above-ground biomass ratio of 0.585 and nonstructural carbohydrate concentration of 21.7 mg g-1.[4]

Distribution

Gymnopogon ambiguus is generally found in the eastern United States, from Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, and Iowa south to Florida, Kansas, Missouri, and Texas.[5] More specifically, G. ambiguus is found from southern New Jersey west to Kentucky, Ohio, and Missouri, south to southern Florida and Texas.[1]

Ecology

Habitat

General habitats of G. ambiguus include glades, prairies, dry pinelands and woodlands, dry fields, and barrens.[1] This species has been observed to grow in open pine woods along the edges of depression ponds, longleaf pine-oak-wiregrass sandhill communities, sparsely wooded ecotone borders of limestone glades, longleaf pine-turkey oak flats and sand ridges, xeric sand pine scrub, upland pine oak woodlands, and clearings within mixed woodland forests. This plant has been seen growing in open and partial shaded environments in dry, loamy, and loose sands and well as moist sandy clay loam. Also growing in disturbed areas, G. ambiguus has been observed in powerline corridors, along trails, on pine plantations, and on open fields. [6] As well, it has been shown to benefit from the overstory being thinned, but not clearcut.[7] A study exploring longleaf pine patch dynamics found G. ambiguus to be most strongly represented within stands of longleaf pine that are between 50-130 years of age.[8] G. ambiguus is an indicator species for the North Florida Subxeric Sandhills community type and is frequent and abundant in the Clayhill Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[9]

G. ambigus has shown regrowth in reestablished native coastal plain habitats that were disturbed by agriculture in South Carolina, making it an indicator species for post-agricultural woodlands.[10] However, it was found to become absent in response to soil disturbance by military training in west Georgia. It has shown resistance to regrowth in reestablished longleaf pine forests that were disturbed by these activities.[11] G. ambiguus was found to be neutral in its short-term response to single mechanical soil disturbances as well as in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[12]

G. ambiguus mostly prefers soils that acidic that are composed of sand, cherty residue, or sandstone.[13] G. ambiguus is considered an indicator species of the north Florida subxeric sandhills habitat, and a characteristic species of the shortleaf pine-oak-hickory community in the Red Hills Region of northern Florida and southern Georgia.[14][15]

Associated species includes Pinus palustris, Quercus falcata, Baptista hirsuta, Quercus nigra, Pterocaulon, stillingia, Heterotheca, Liquidambar styraciflua, Aristida stricta,Solidago, Andropogon, Sorghastrum, Pinus taeda, and Bluestem.[6]

Phenology

This species commonly flowers between August and October.[1] Flowers and fruits have been observed on this species from September to November.[6][16]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by gravity. [17]

Fire ecology

Gymnopogon ambiguus occurs on annually burned pine plantations,[6] such as the Pebble Hill plantation in north Florida[18] where populations persist through repeated annual burning.[19] This species is dependent on fire disturbance, and fire suppression leads to the decline of this species.[13] Although it can be found in areas that are fire-excluded, populations show significant decreases over time.[20] Implementing a fire regiment has been shown to increase frequency of this species.[21] As for seasonality, it has been shown to benefit from winter burns rather than spring or summer burn regiments.[22] As well, it has been seen to benefit most from a low fire-return interval.[23]

Herbivory and toxicology

This species is eaten by white-tailed deer, where it comprised of their diets more in the summer than in the winter.[24] It is one of the principal grasses that is eaten by deer.[25] Cattle will forage fresh G. ambiguus growth after a burn, but mature grass becomes unpalatable.[26]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

This species is listed as extirpated by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Nature Preserves and by the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources; it is listed as presumed extirpated by the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, Division of Natural Areas and Preserves. As well, it is listed as a species of special concern by the Kentucky State Nature Preserves Commission.[5] Due to this as well as its susceptibility to intense disturbances like logging or heavy grazing, it is listed as a G4 global status. The biggest threats to G. ambiguus are fire suppression and habitat destruction, so fire regiments should be implemented for the management of this species. Fire regiments should mimic natural burn cycles, and intense disturbances (logging, vehicle traffic, heavy grazing) should be ceased. Since it is usually scattered infrequently in its habitat, large expanses should be set aside for this management for a healthy population. Seasonality of burns should be studied more to find whether this affects G. ambiguus populations. If grazing is implemented, it should be on a rotational program to prevent heavy grazing.[13]

This species has a high restoration potential due to its susceptibility to fire suppression and intense disturbance. If management practices like fire regiments and ceasing of habitat destruction or disturbance are implemented, then areas can most likely be restored for G. ambiguus populations to increase. This species requires ground species that are already established, and restoration efforts of bare ground will most likely not be successful. When these management techniques are used, the presence of this species in the seed bank will help restore the species; without seeds present in the seed bank, populations of G. ambiguus will not be fully restored.[13]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 118. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Diaz-Toribio, M.H. and F. E. Putz 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire-maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108: 432-442.

- ↑ Diaz‐Toribio, M. H. and F. E. Putz. 2021. Underground carbohydrate stores and storage organs in fire‐maintained longleaf pine savannas in Florida, USA. American Journal of Botany 108(3):432-442.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 17 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 .Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, Wilson Baker, Robert K. Godfrey, James R. Burkhalter, Angus Gholson, Richard D. Houk, Robert Kral, Andre F. Clewell, D. L. Martin, S. T. Cooper, Sidney McDaniel, R.A. Norris, D. C. Hunt, R. Komarek, and J.M. Kane. States and Counties: Florida: Gadsden, Jackson, Jefferson, Lafayette, Leon, Madison, Marion, Nassau, Putnam, Santa Rosa, and Wakulla. Georgia: Grady and Thomas.

- ↑ Brockway, D. G. and C. E. Lewis (2003). "Influence of deer, cattle grazing and timber harvest on plant species diversity in a longleaf pine bluestem ecosystem." Forest Ecology and Management 175: 49-69.

- ↑ Mugnani et al. (2019). “Longleaf Pine Patch Dynamics Influence Ground-Layer Vegetation in Old-Growth Pine Savanna”.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Brudvig, L.A., E Grman, C.W. Habeck, and J.A. Ledvina. (2013). Strong legacy of agricultural land use on soils and understory plant communities in longleaf pine woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 310: 944-955.

- ↑ Dale, V.H., S.C. Beyeler, and B. Jackson. (2002). Understory vegetation indicators of anthropogenic disturbance in longleaf pine forests at Fort Benning, Georgia, USA. Ecological Indicators 1(3):155-170.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 [[1]] NatureServe Explorer. Accessed: May 17, 2019

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2013). "Prior prevalence of shortleaf pine-oak-hickory woodlands in the Tallahassee red hills." Castanea 78(4): 266-276.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 17 MAY 2019

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.

- ↑ Haywood, J. D., et al. (1995). Responses of understory vegetation on highly erosive Louisiana soils to prescribed burning in May. Asheville, NC, USDA Forest Service, Research Note SO-383: 8.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Mehlman, D. W. (1992). "Effects of fire on plant community composition of North Florida second growth pineland." Bulletin of the Torrey Botanical Club 119(4): 376-383.

- ↑ Thill, R. E. (1983). Deer and cattle forage selection on Louisiana pine-hardwood sites. New Orleans, LA, USDA Forest Service.

- ↑ Thill, R. E. (1984). "Deer and cattle diets on Louisiana pine-hardwood sites." The Journal of Wildlife Management 48(3): 788-798.

- ↑ Byrd, Nathan A. (1980). "Forestland Grazing: A Guide For Service Foresters In The South." U.S. Department of Agriculture.