Gamochaeta purpurea

Common names: purple everlasting; spoonleaf purple everlasting; purple cudweed

| Gamochaeta purpurea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo by the Atlas of Florida Plants Database | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida - Dicots |

| Order: | Asterales |

| Family: | Asteraceae |

| Genus: | Gamochaeta |

| Species: | G. purpurea |

| Binomial name | |

| Gamochaeta purpurea L. | |

| |

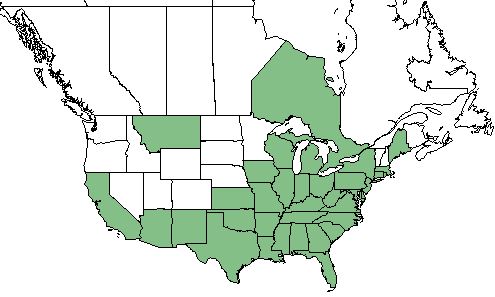

| Natural range of Gamochaeta purpurea from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Contents

[hide]Taxonomic Notes

Synonyms: Gnaphalium purpureum Linnaeus; Gnaphalium purpureum Linnaeus var. purpureum; Gnaphalium purpureum Linnaeus var. spathulatum (Lamarck) Baker; Gnaphalium peregrinum Fernald; Gnaphalium spathulatum Lamarck.[1]

Varieties: none.[1]

Description

G. purpurea is a weedy forb in the Asteraceae family native to North America. It that can be either annual or biennial [2]. It can reach a height of 1.25 feet, and forms a basal rosette with leaves alternate and spatulate. [3]

Distribution

G. purpurea ranges from northeast California through the southeastern and eastern United States and southeastern Canada. It has also been introduced in Hawaii and the Pacific Basin.[2] As well, it is adventive in the western United States as well as Mexico, South America, and elsewhere.[4]

Ecology

Habitat

G. purpurea can be found in disturbed areas such as roadsides, fields, and pastures.[4] It also has been observed in a calcareous coastal hardwood habitat, amongst roadside grasses, in various disturbed areas such as roadside ditches and fallow fields, in firelanes, boggy hillsides, deciduous clearings, lake banks, and semi-shaded areas of various woodlands. Soils include drying loamy sand, moist sand, clay-like soil, and sandy-peat. It also has been observed to grow in moderately disturbed areas as well as normal disturbed areas.[5]

Phenology

Generally, G. purpurea flowers from late March until September.[4] It has been observed to flower from March to June.[6][5] However, it has been observed to be flowering during November and January. As well, it has been observed fruiting in May.[5]

Seed dispersal

The seeds of this species are thought to be dispersed by wind.[7]

Seed bank and germination

A study on longleaf pine habitats found G. purpurea present in the seed bank of both disturbed and non-disturbed sites.[8] Another study also found this species in the seed bank 3 years and 10 years after a fire disturbance.[9]

Fire ecology

It grows in habitats that are commonly fire disturbed.[5] The seeds of G. purpurea also persist in the seed bank after a fire disturbance.[9]

Herbivory and toxicology

G. purpurea has been observed to host leafhoppers such as Empoasca fabae (family Cicadellidae).[10] It consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for small mammals, and 5-10% of the diet for various large mammals.[11]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

G. purpurea is listed as endangered by the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, and by the New York Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Land and Forests. It is also listed as a species of special concern by the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, listed as possibly extirpated by the Maine Department of Conservation, Natural Areas Program, and listed as historical by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management.[2]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Weakley, A.S. 2015. Flora of the southern and mid-atlantic states. Working Draft of 21 May 2015. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 USDA Plants Database URL:https://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=Gapu3

- Jump up ↑ Gee, K. L., et al. (1994). White-tailed deer: their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 Weakley, A. S. (2015). Flora of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. Chapel Hill, NC, University of North Carolina Herbarium.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: May 2019. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, L. Baltzell, K. Craddock Burks, A. F. Clewell, James R. Coleman, George R. Cooley, Patricia Elliot, G. Fleming, Suellen Folensbee, P. Genelle, Robert K. Godfrey, Lisa Keppner, R. Komarek, R. Kral, O. Lakela, Sidney McDaniel, Richard S. Mitchell, R. A. Norris, John C. Ogden, Cindi Stewart, Alush Shilom Ton, L. B. Trott, Kenneth A. Wilson, and Carroll E. Wood, Jr. States and Counties: Florida: Baker, Bay, Calhoun, Citrus, Collier, Dixie, Escambia, Franklin, Gadsden, Gilchrist, Holmes, Jackson, Jefferson, Lake, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Madison, Martin, Okaloosa, Orange, Pasco, Putnam, Wakulla, and Washington.

- Jump up ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 22 MAY 2018

- Jump up ↑ Cohen, S., et al. (2004). "Seed bank viability in disturbed longleaf pine sites." Restoration Ecology 12: 503-515.

- Jump up ↑ Discoverlife.org [1]

- Jump up ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.