Galium pilosum

| Galium pilosum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Photo taken by Kevin Robertson | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Division: | Magnoliophyta - Flowering plants |

| Class: | Magnoliopsida – Dicotyledons |

| Order: | Rubiales |

| Family: | Rubiaceae |

| Genus: | Galium |

| Species: | G. pilosum |

| Binomial name | |

| Galium pilosum Aiton | |

| |

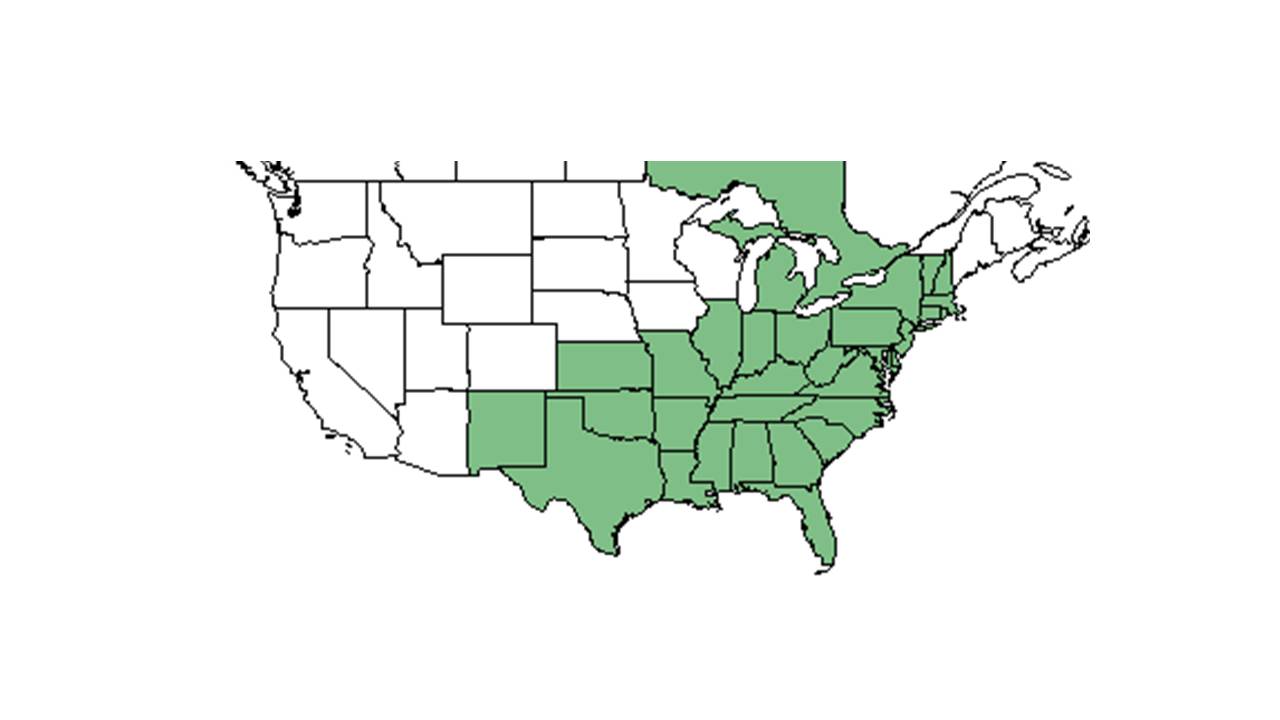

| Natural range of Galium pilosum from USDA NRCS Plants Database. | |

Common name: hairy bedstraw

Contents

Taxonomic notes

Synonyms: none[1]

Varieties: Galium pilosom Aiton var. pilosum; G. pilosum Aiton var. puncticulosum (Michaux) Torrey & Gray[1]

Two varieties, including var. pilosum and var. puncticulosum, have been distinguished but need additional study.[1]

Description

Generally, Galium genus are "perennial or annual herbs, the stems weak, often scabrous; the roots often red or orange. Leaves whorled, entire. Flowers in simple or profusely branched cymes or the inflorescence reduced and the flowers 1-several and axillary; sepals usually obsolete, corolla rotate, 3-5 lobed; stamens 3-5. Fruit dry or sometimes fleshy, indehiscent, subglobose or reniform, or if the two carpels both develop and stay together the fruit broader than long." [2]

Specifically, for this species, G. pilosum are "perennial, the stems erect or ascending, unbranched except in the elongate inforescence, 3-8 dm tall, smooth, pilose. Leaves 4 per node, elliptic to weakly ovate, 1-2.5 cm long, 6-12 mm wide, mucronate, pilose-hispid, glandular-punctate beneath. Corolla white, greenish or shaded with maroon. Fruit dry, brown, or black, bristly, 2-3 mm long, 3-4 mm broad." [2]

Distribution

Galium pilosum is natively distributed from southern New Hampshire west to Michigan, northern Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas, and south to central peninsular Florida and Texas.[1] It is also native to the Canadian province of Ontario.[3]

Ecology

Habitat

Generally, G. pilosum can be found in woodland borders, forests, and clearings. It is quite common.[1] This species has been found in wet flatwoods, mixed hardwoods, longleaf pine-wiregrass savannas, coastal and cabbage palm hammocks, river floodplains, rich woodlands, grassy and shrubby thickets, coastal dunes, sandy ridges, and near ponds. They are found to grow in partial shade and under open canopies of pinewoods in well drained moist sandy soils, drying loamy sands, limestone outcrops, or dry loamy sands during drought. They also have been observed growing in disturbed areas such as picnic areas, along roadsides, in powerline corridors, along trails, on sand pine plantations,in borrow pits, on bulldozed areas, and in "battered" limestone glades.[4] It is considered an indicator species of the north Florida longleaf woodlands habitat.[5] G. pilosum was found to be neutral in its long-term response following cessation of repeated soil disturbance.[6]

Associated species includes Smallanthus, Schisandra, Collinsonia, Nyssa, Ulmus, Pinus, Quercus, Carya, Aristida stricta, Acer, Magnolia, Ilex, Aesculus, Pinus elliottii, Giallardia pulchella, and Quercus laevis. Also includes cabbage palm.[4]

Galium pilosum is an indicator species for the North Florida Longleaf Woodlands community type as described in Carr et al. (2010).[7]

Phenology

G. pilosum generally flowers from May until August.[1] It has been observed flowering in March, from May through August and October through November with peak inflorescence in June.[8][4] It has been observed fruiting from June through November.[4]

Seed dispersal

This species is thought to be dispersed by translocation on animal fur or feathers. [9]

Fire ecology

This species can be found in annually burned pinelands[4] as shown in the populations that persist through repeated annual burns.[10][11] G. pilosum has been shown to increase in cover and frequency in response to fire disturbance.[12] It has been observed flowering in July following a March prescribed burn in research plots in a longleaf pine-wiregrass native community in southern Georgia.[13] It was found to benefit most from winter burn regiments rather than summer or spring burn regiments.[14] While it commonly grows in fire-disturbed areas, it can also grow in fire-excluded areas.[15]

Herbivory and toxicology

Galium pilosum consists of approximately 2-5% of the diet for various large mammals.[16] This species is most significantly used by white-tailed deer during the summer months.[17]

Conservation, cultivation, and restoration

This species is listed as endangered by the New Hampshire Division of Forests and Lands, Natural Heritage Inventory.[3]

Cultural use

Photo Gallery

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Weakley, A.S. 2020. Flora of the Southeastern United States. Edition of 20 October 2020. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Radford, Albert E., Harry E. Ahles, and C. Ritchie Bell. Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas. 1964, 1968. The University of North Carolina Press. 984-6. Print.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 USDA, NRCS. (2016). The PLANTS Database (http://plants.usda.gov, 13 May 2019). National Plant Data Team, Greensboro, NC 27401-4901 USA.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Florida State University Robert K. Godfrey Herbarium database. URL: http://herbarium.bio.fsu.edu. Last accessed: June 2014. Collectors: Loran C. Anderson, R.K. Godfrey, Robert Kral, Cecil R Slaughter, Gil Nelson, W. H. Lewis, R. A. Norris, R. F. Doren, Chris Cooksey, R. Komarek, M. Davis, Lisa Keppner, Thomas E. Miller, C. Jackson, Gwynn W. Ramsey, R. S. Mitchell, H. Larry Stripling, Mabel Kral, and Wilson Baker. States and Counties: Florida: Citrus, Clay, Franklin, Gadsden, Gulf, Hernando, Jackson, Leon, Levy, Liberty, Nassau, Okaloosa, Santa Rosa, Suwannee, Wakulla, and Washington. Georgia: Grady and Thomas.

- ↑ Carr, S. C., et al. (2010). "A Vegetation Classification of Fire-Dependent Pinelands of Florida." Castanea 75(2): 153-189.

- ↑ Dixon, C. M., K. M. Robertson, A. M. Reid and M. T. Rother. 2024. Mechanical soil disturbance in a pine savanna has multiyear effects on plant species composition. Ecosphere 15(2):e4759.

- ↑ Carr, S.C., K.M. Robertson, and R.K. Peet. 2010. A vegetation classification of fire-dependent pinelands of Florida. Castanea 75:153-189.

- ↑ Nelson, G. PanFlora: Plant data for the eastern United States with emphasis on the Southeastern Coastal Plains, Florida, and the Florida Panhandle. www.gilnelson.com/PanFlora/ Accessed: 9 DEC 2016

- ↑ Kirkman, L. Katherine. Unpublished database of seed dispersal mode of plants found in Coastal Plain longleaf pine-grasslands of the Jones Ecological Research Center, Georgia.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Unpublished data collected from Pebble Hill Fire Plots, Pebble Hill Plantation, Thomasville, Georgia.

- ↑ Glitzenstein, J. S., D. R. Streng, R. E. Masters, K. M. Robertson and S. M. Hermann 2012. Fire-frequency effects on vegetation in north Florida pinelands: Another look at the long-term Stoddard Fire Research Plots at Tall Timbers Research Station. Forest Ecology and Management 264: 197-209.

- ↑ Taft, J. B. (2003). "Fire effects on community structure, composition, and diversity in a dry sandstone barrens." Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 130: 170-192.

- ↑ Robertson, K.M. Observation on Pebble Hill Plantation, near Thomasville, Georgia, July 2015.

- ↑ Kush, J. S., et al. (2000). Understory plant community response to season of burn in natural longleaf pine forests. Proceedings 21st Tall Timbers Fire Ecology Conference. Fire and forest ecology: innovative silviculture & vegetation management, Tallahassee, FL, Tall Timbers Research, Inc.

- ↑ Clewell, A. F. (2014). "Forest development 44 years after fire exclusion in formerly annually burned oldfield pine woodland, Florida." Castanea 79: 147-167.

- ↑ Miller, J.H., and K.V. Miller. 1999. Forest plants of the southeast and their wildlife uses. Southern Weed Science Society.

- ↑ Gee, K. L., et al. (1994). White-tailed deer: their foods and management in the cross timbers. Ardmore, OK, Samuel Roberts Noble Foundation.